Teenager Adnan (left) reached Preston, Lancashire after Taliban had returned to power in Afghanistan; Mo Farah Multiple Olympic and world champion Mo Farah was brought to Britain from Djibouti at the age of nine. (Screengrab & File)

Teenager Adnan (left) reached Preston, Lancashire after Taliban had returned to power in Afghanistan; Mo Farah Multiple Olympic and world champion Mo Farah was brought to Britain from Djibouti at the age of nine. (Screengrab & File)Fresh off the boat after sailing over the waters connecting Greece and Italy, and a subsequent ride on an empty lorry that took him past the UK-French border, Adnan would reach Preston, a small city in Lancashire. That was to be the last leg of the Afghan teenager’s desparate journey to a country that was very different from the one he had left behind.

This was some time in August 2021. It was when the Taliban had returned to power and every border post was witnessing an exodus.

Even before the change of guard, Adnan had no access to education. His village didn’t even have electricity. Bad, they feared, would turn to worse soon.

Not surprising, Adnan agreed to the outlandishly ambitious plan of crossing continents on foot with virtually empty pockets.

When a new face turned up to cricket training, @flintoff11 soon knew he had a secret weapon on his hands.

He popped round to see Adnan's foster parents, but wasn't ready for what he heard.

Adnan's story is a remarkable one. Watch Freddie Flintoff's Field of Dreams at 8pm. pic.twitter.com/ftN3EfsoaS

— Test Match Special (@bbctms) July 12, 2022

By the time he reached Preston, he was famished and broke. Too exhausted to be on the run, he handed himself to the police. A night under bars, an appeal for asylum and a sensitive system’s warm embrace – this would be the sequence of events that got Adnan a roof over his head and the caring umbrella of foster parents. Elaine and Barry – an aged couple – would be his guardian angels in this cold new place.

The young Afghan boy’s first two weeks were spent at his new home’s living-room couch staring at a television. There was too much to process for the young receptive mind. When in his room, he would sit quietly on his bed. The culture was alien, the surroundings new. He didn’t even know any English.

However hard Elaine and Barry tried, the communication lines with the new addition to their family couldn’t get switched on. Finally, it was the father, an avid golfer, who got the breakthrough.

Elaine recalls the moments: “He kind of sat here for two weeks just watching the telly. And then one day Barry said, “Football?” He went, ‘No, no, no football’. When Barry asked ‘Cricket?’, Adnan’s eyes lit up and he responded: ‘Cricket, cricket’.”

As Elaine speaks, Freddie Flintoff, England’s iconic cricketer, listens with interest.

These are scenes from the BBC documentary series Freddie Flintoff’s Field of Dreams. For the filming, the man of many talents, the ‘cricketer turned boxer turned adventurer turned anchor’ is back in his neck of woods. It’s where he picked up cricket over football just because his father and grandfather wore whites and lugged kits to the local grounds on weekends. Like he says if not for this family tradition, cricket was too high-class a pursuit for a plumber’s son.

Flintoff recalls his village cricket days – playing with the Patels from the neighbourhood and some West Indians with the capacity to hit big shots. Migrants and the local working-class have always been part of the English ecosystem but their representation in the national team isn’t proportional to their numbers at grass root level.

A three-year old study, Elitist Britain 2019, ranked cricket among the Top 10 professions, along with politicians and military bigwigs, that were dominated by those attending private school. Football was lopsidedly proletarian. The 2019 survey showed 43 per cent of active male England cricketers came from private schools. In football, the corresponding number was 5 per cent.

As part of the documentary, Flintoff, like a committed missionary, is on a cricket conversion drive. His message: Cricket isn’t posh, people do join. As part of the reality TV kind of storyline, England’s rare non-private school hero forms a team by hand-picking an eclectic bunch of working-class kids from the mean streets that have an air of aggression.

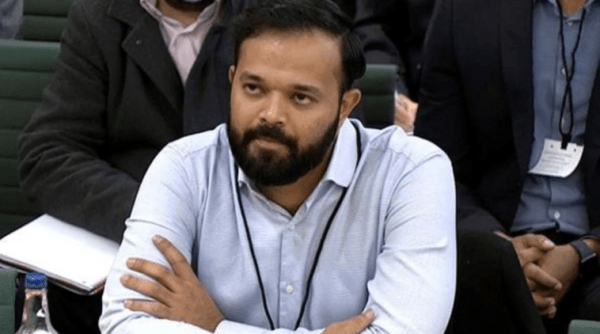

Former cricketer Azeem Rafiq gives evidence during a parliamentary hearing at the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) committee on sport governance at Portcullis House in London, Tuesday, Nov. 16, 2021. (Video grab House of Commons via AP)

Former cricketer Azeem Rafiq gives evidence during a parliamentary hearing at the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) committee on sport governance at Portcullis House in London, Tuesday, Nov. 16, 2021. (Video grab House of Commons via AP) It’s too much of a coincidence that the documentary has hit the air around the time Yorkshire CC, under a chairman with Indian-roots, is trying to get over its ugly racist past and aspires to embrace inclusivity. Change takes time. Earlier this month, the club’s one-time player Azeem Rafiq, the whistle blower responsible for exposing Yorkshire’s toxic culture that targeted Asians, claimed that his family still faces “threats, attacks and intimidation”.

Adnan, 16, is the Flintoff of Sir Freddie’s team. When he picked the game in Afghanistan, any piece of wood would get called a bat and a ball would, well, be a spherical stone. Now, he wears sparkling whites and lugs a topline cricket kit bag. He is a left-armer who can bend his back and bowl fast. He can also give the ball a serious wallop. He’s the stand-out serious cricketer of this ‘fly on the wall’ documentary that is getting rave reviews.

While Adnan’s heart-warming story was unfolding, the world was tuned in to an emotional twist to the most endearing immigrant story to emerge from British shores.

Through this documentary I have been able to address and learn more about what happened in my childhood and how I came to the UK. I'm really proud of it and hope you will tune into @BBC at 9pm on Weds to watch. pic.twitter.com/rqZe41gFm8

— Sir Mo Farah (@Mo_Farah) July 11, 2022

Mohammad Farah, in a BBC documentary, announced that the real Mohammad Farah was someone living in Djibouti. It was a jaw-dropping confession. Be it in his interviews, autobiography or even when with his wife and children, Britain’s Hall of Fame Olympian and OBE-recipient had lived a lie from the time he was trafficked from Somaliland as a four year old after his father died during the civil war. At an age when parents indulge children, Mo Farah was made to clean, cook and be the all-day nanny to younger kids of his fraudsters who forged his passport and posed as his foster parents.

In comparison, Adnan’s Preston switch had been easier. Older than Mo Farah when he was parachuted to England and thus better equipped to deal with the first-world shift, the Afghan was lucky to have kinder parents. But eventually it was sport that gave the two the acceptability in the society they so aspired to be part of.

It helped them break ice, open doors, bring down the glass ceiling and, in Mo Farah’s case, reach those lofty heights where only national heroes reside. Europe’s lenient policy to welcome refugees – even if it was economics and not empathy that made them do that – has got them unexpected sporting benefits. Ethnic diversity makes teams shake off sameness. They become versatile, dynamic and dangerously unpredictable.

Asian spinners and crafty football playmakers with links to Latin America and Africa have historically added new dimensions to the teams that have traditionally lacked these skill sets. Cricketer with Pakistan roots, Moeen Ali adds variety to the pace-centric England attack just like Imran Tahir did to South Africa. Zinedine Zidane has Algerian parentage, Deco was born in Brazil. They pulled the strings that made France and Portugal play eye-pleasing fusion football.

Like Mo Farah, they are all tough men. As under-privileged outsiders they were forced to fight biases at every crossroad. They all needed to train longer, run faster and be extra smart to take the place of some home-grown players. The harrowing life experiences would make them better equipped to deal with pressures and lows of professional sport. What is a defeat on track for Sir Mo when he lost his entire family and identity as a four year old.

The mental fortitude of men like Farah, and even Adnan, has got forged because of what they have gone through early in life. Adnan can be trusted to nail a yorker on the final ball of a T20 game. Having risked his life with his leap into the unknown, he wouldn’t let fear of failure at cricket enter his mind.

Do send your feedback to sandydwivedi@gmail.com

Subscriber Only Stories

Sandeep Dwivedi

National Sports Editor

The Indian Express

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.