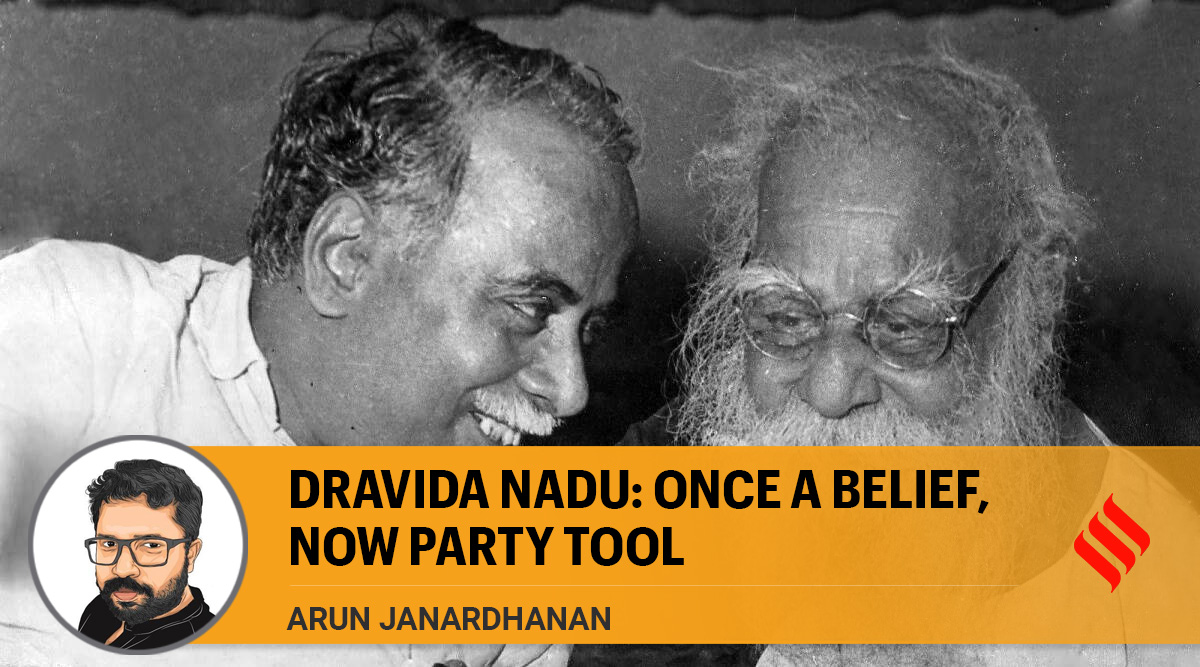

DMK founder Annadurai (left) with Periyar, who first coined term Dravida Nadu. (File)

DMK founder Annadurai (left) with Periyar, who first coined term Dravida Nadu. (File)Another high-voltage debate erupted in Tamil Nadu last week when DMK leader and former Union minister A Raja brought up the issue of a “separate Tamil Nadu”. At a party meeting, Raja asked the BJP-ruled Centre not to compel the Dravidian party to revive its demand, saying, “Don’t push us to return to the Periyar route. Don’t corner us. Don’t force us to raise a separate Tamil Nadu demand again. Give us the state autonomy we deserve. We will not rest and will battle until we achieve our goal.”

Was Raja’s speech indicative of a broader scheme, or was it merely political posturing in a polarised polity? After all, why would a ruling party leader discuss an idea that borders on separatism?

In a state that proudly wears its exceptionalism on its sleeve, many interpreted Raja’s remarks as an inevitable pushback at a time when the BJP-ruled Centre is seen as advocating a national identity that subsumes all others.

“I’m not supporting Raja’s remarks, but I understand him. When you push for One Nation, One Religion and One Language in a nation like India that has so many diverse ethnic identities, you inevitably force other ethnicities to push back. Raja’s argument was also about an identity that does not want to be steamrolled or trampled,” said Ramu Manivannan, retired professor of political science at the University of Madras.

Subscriber Only Stories

The ruling DMK is an offshoot of the Dravida Kazhagam (DK), a movement against social inequities beyond electoral politics. Thanthai Periyar, a social reformer who founded the DK, first coined the term Dravida Nadu in the 1920s. If the idea was to liberate Tamils from the caste-ridden Hindu religion, its basis lay in the pride shared by the majority Tamils fortified by oral histories, mythology, culture, literature, and now, radiocarbon-dated historical finds.

Periyar’s aspiration for a separate country was based on this notion of a different or unique identity. His assumption that the caste system would persist in India as long as the descendants of Manu were in place led him to the idea. When he realised caste imbalances were unavoidable, he mooted reservation as a provisional solution for fair representation, but, of course, thought of it only as a temporary arrangement until ‘Dravida Nadu’ was established.

To provide balance and coherence to the Dravida Nadu notion, both Periyar, a Kannadiga by birth, and C N Annadurai, Periyar’s follower who founded the DMK, featured not just Tamils but also Keralites, Telugus and Kannadigas too in literature about a broader Dravida concept.

Annadurai, who pursued the same line for more than a decade, abandoned the Dravida Nadu goal in 1962 during the India-China war, reportedly for fear of treason. Annadurai said that his concerns remain, but that the DMK was not pressing for it owing to the war. Periyarists, via their periodicals Kudiyarasu and Viduthalai, criticised Annadurai for diluting the cause.

Later, under Annadurai, the DMK shifted its goal to the idea of “state autonomy”, which was mostly about obtaining a proportional share of the taxes from the Union government. Hardcore Tamil nationalists, on the other hand, continue to term Annadurai’s change of stance a “compromise formula” for political survival.

After Annadurai’s death, Karunanidhi took up the cause of state autonomy and kept it alive throughout Indira Gandhi’s term. In 1974, Karunanidhi sought — and got — the right for Chief Ministers to raise the national flag on Independence Day. Until then, the President and state governors would unfurl national flags on Republic Day while Independence Day was a low-key ceremony.

Perhaps due to Annadurai’s subsequently softened stand, ‘Dravida Nadu’ didn’t feature in any of the Tamil movies of the 1950s and 1960s that were major propaganda tools for the politics of those times. One of the stray references was in Malayitta Mangai (1958) — produced and written by Kannadasan, considered among independent India’s prominent lyricists — that featured the song Engal Dravida Ponnade (Our beloved Dravida Nadu).

For a long time, especially after Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, there was hardly any talk of Dravida Nadu.

Among the few voices that has consistently invoked and romanticised the idea of a promised Tamil land is Seeman, leader of the Naam Tamilar Katchi (NTK), a party that has had a slow and consistent growth in elections for over a decade, with 6.5 per cent vote share in the last Assembly election. Seeman, also a fiery orator, said Raja’s statement was not a call for a separate state but a protest against the BJP’s “divisive” politics and policies.

Saying it wasn’t necessary to have a separate state to solve problems, Seeman said, “If I were the Chief Minister, I would have organised a major march and conference of all South Indian Chief Ministers with a crowd of at least 10 lakh people in attendance. I believe such a mobilisation would be adequate to overcome the challenges of state autonomy India.”

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.