Updated: July 4, 2022 4:07:15 am

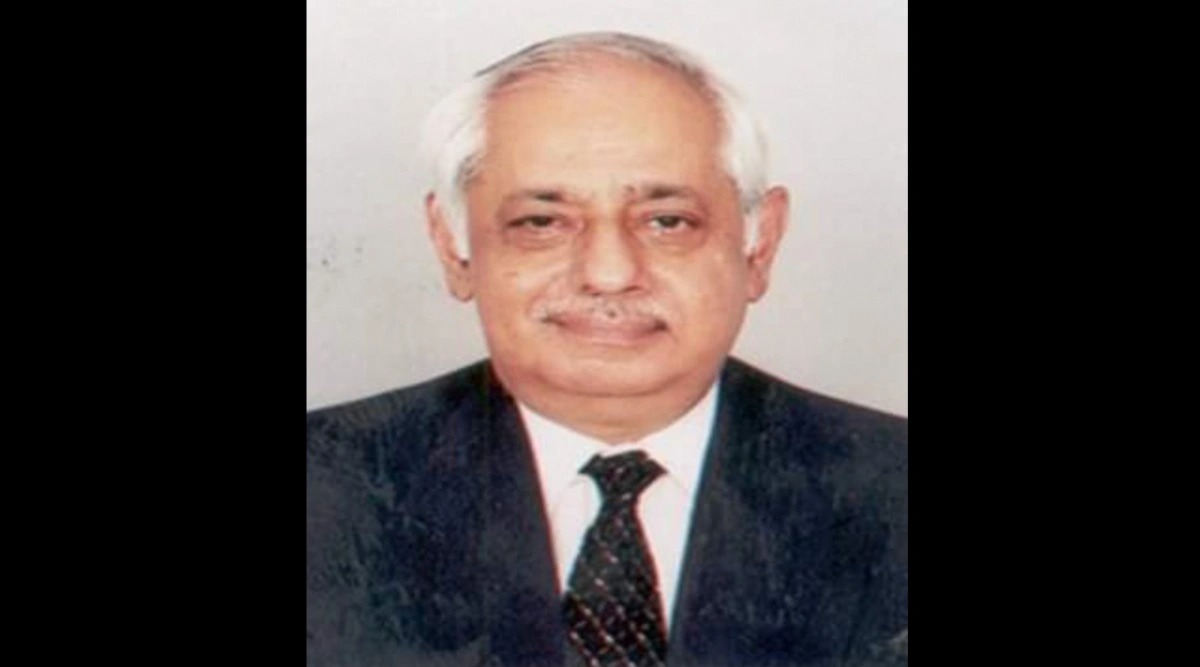

Satinder Kumar Lambah (Image: Facebook/Unofficial: Diplomats of India)

Satinder Kumar Lambah (Image: Facebook/Unofficial: Diplomats of India)Last week, when Satinder Kumar Lambah breathed his last, India lost one of her finest diplomats. Sati, as his friends called him, went away just a fortnight before his 82nd birthday, after a two-year-and-nine-month-long battle with terminal cancer.

A spontaneous and deep sense of loss was immediately felt. This encompassed generations of his colleagues in the foreign service, a wide circle of political leaders, civil servants, armed forces officers, foreign and domestic intelligence services, leaders of commerce and industry, journalists, professors and students and many others. The groundswell of tributes was all the more remarkable considering that Sati was known for the low public profile he maintained, despite holding numerous high-profile posts in our foreign and national security establishment.

Sati’s assignments included serving as India’s ambassador to Germany and Russia during critical geopolitical transitions in these countries, as high commissioner to Pakistan in turbulent times, as Special Envoy on Afghanistan, as head of our National Security Advisory Board, and of course as independent India’s longest-serving Special Envoy of the Prime Minister during his back-channel talks with his Pakistani counterparts. I will not dwell on any of these issues here as Sati recently completed a book on his involvement with India-Pakistan relations, which addresses most issues of interest to experts and laypersons alike. Instead, I would like to identify some of his attributes which I feel accounted for his professional accomplishments and the respect and affection he inspired in those with whom he came in contact.

My personal interactions with Sati span many decades. In the early years of our careers, in Moscow in 1968, I moved into his apartment number 111 in a building for diplomats, inherited his car number plate 222, but alas not his diplomatic identity card number 333. Three decades later in 1998, we exchanged posts, residences and flag cars in Russia and Germany. My subsequent move from Bonn to Berlin, when the capital moved, was also greatly facilitated by Sati’s efforts. Against difficult odds, he had succeeded in securing the land for our new embassy premises at the best location in Berlin. In the decades in between, Sati was my one-stop go-to person on all matters relating to Pakistan and Afghanistan, wherever I happened to be, whether it was in the PMO under four successive PMs, in Russia, in the UK or the USA. Even now I am struggling to fill Sati’s boots after taking over from him as President of the Federation of Indo-German Societies in India.

Best of Express Premium

There were many attributes that put Sati in a class apart.

First, he was a consummate professional who prepared thoroughly and kept himself updated constantly. He could prepare briefs at less than a day’s notice. He exuded an air of quiet confidence from the earliest stages of his career as special assistant to the ambassador in Moscow and thereafter as under-secretary (Americas) in the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA). Thus, it was not surprising when members of a high-level US Congressional delegation gravitated towards under-secretary Sati, mistaking him to be the senior-most official in the room, while his redoubtable but warm-hearted boss, C B Muthamma, looked on with bemused indulgence.

Second, he understood the importance of brevity. Sati’s were among the few telegrams or notes that I could show without abbreviations or highlighting to prime ministers.

Third, he maintained excellent personal equations across the board. His ready wit and self-deprecating humour endeared him to all. With his junior colleagues he was always accessible at all times, be it at the office or at home. With his wife Nina, he created a home that was always gracious and welcoming to all officers and their families. Sati set high standards by personal example, and he always valued the contributions made by his colleagues. In the process, he became a mentor to generations of officers.

Fourth, during negotiations, he never underestimated his interlocutors. He made a special effort to take a measure of the man, not just relying on two-dimensional bio data but forming a multi-dimensional perspective on the person. This enabled him to find common ground and work towards mutual understanding.

Fifth, he was a believer in institutions. Sati carried out reforms in the functioning of the MEA and built up a storehouse of institutional knowledge. He was one of the earliest practitioners of what is now called economic diplomacy. He believed in the strength of people-to-people contacts and worked to mobilise local communities, including the Indian diaspora long before it became a policy priority.

Sixth, Sati’s defining characteristic was his humaneness. An early example of this is from late December 1971, when I was visiting Delhi from Moscow and Sati was on his way to set up the High Commission in Dhaka. On our way to dinner, Sati spotted a hit-and-run scooter accident. A young army officer was lying in a pool of blood while bystanders simply watched or walked away. Sati immediately stopped to help and rushed the injured officer in his car to the nearest hospital.

Sati was an unabashed proponent of our core national interests, and at the same time, of certain universal values. He believed that we should not define our interests, let alone our identity as a nation, in terms of Pakistan and risk becoming a mirror image of that country. We shared the conviction that our foremost priority should remain social harmony and cohesion at home while maintaining continuous and comprehensive engagement with both our western and northern neighbours.

(The writer is a former diplomat)

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.