Top Searches

- News

- City News

- mumbai News

- How housing rules have shaped Mumbai from 1896 plague to Covid

How housing rules have shaped Mumbai from 1896 plague to Covid

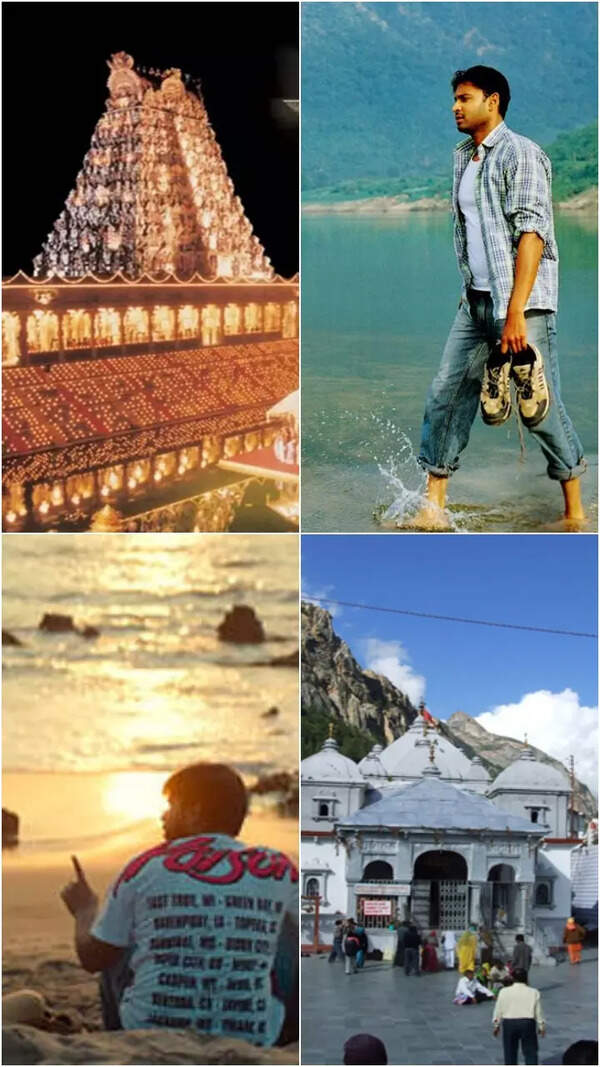

This Mahim high-rise with seven residential floors over 10 storeys of parking, is a reminder of the 1991 rules that made parking space a must for buildings

A former ice factory in Fort introduced architect Rachita Vishwanath to a cold truth about Mumbai last week. On a brick wall inside this peculiar, restored building were photos of other strange buildings such as one in Bandra whose visible, external spine holds up the additional floors that it grew in the 1960s when the BMC allowed landowners to build additional floors to existing structures. Splashed across the opposite brick wall was a timeline that compressed the century-long development of housing laws in city - spanning the global Bubonic Plague of 1896 to the Covid-19 pandemic - into four neat phases and phrases: 'Urban Explosion', 'Urban Sprawl', 'Urban Implosion' and 'Urban Exaltation'.

"You can see greed come into play here," said Vishwanath, pointing to the 'Urban Implosion' panel which included graphical sketches of post-globalisation skyscrapers such as a mushroom-shaped skyscraper in Mahim, whose seven residential floors sit awkwardly above its 10-storey parking podium - an unsubtle reminder of the 1991 Development Control Regulations (DCR) that had made parking a requirement to be accommodated in buildings.

That the very rulebooks which once sought to decongest the city and help locals combat disease in the aftermath of the 1896 plague have grown to suffocate them and make them sick, is the ironic full circle drawn by 18 graphical sketches of housing units at an ongoing exhibition titled (de)Coding Mumbai. Hardbound copies of these thick rule-books lay open on a table at the exhibition organised by sPare, the research arm of a firm headed by architect Sameep Padora, who had once deadpanned about the current Development Plan (DP) and DCR in a speech: "Don't go by their look. They are fairly light on content."

"In the hundred years that elapsed between the two global contagions, the focus of building codes has shifted from welfare to profit," said Padora, citing not only Mahul's infamous Project-Affected Persons Township (a rehabilitation project intended to house hutment dwellers displaced due to the Brihanmumbai Stormwater Disposal System) now known as a "hellhole" for its skin and respiratory conditions but also a 2018 report that attributed the spread of TB in an SRA project to the lack of ventilation and sunlight.

"Today, it really doesn't matter whether you are living in a free SRA building given by the state or a privately-developed building where an apartment costs you Rs 70 lakh; Mumbai's architecture is slowly killing us," said Padora whose team drew the idea for the exhibition from its earlier study of old structures such as Dadar Parsi Colony's non-commercial multi-family ground-plus-two buildings which sprouted from a scheme that was meant to attract people to settle in the suburbs and Dindoshi's Nagari Nivara Parishad Colony, which derives its sunlit view from the Emergency-era bylaw that "no building should be raised to a height greater than one and a half times the sum of the width of the street on which it stands and the width of the open space between the street and the building".

Another sunny bylaw relegated to housing relic is the '63.5 degree light and air plane' regulation which was part of the city's first development rules framed by a newly-minted Bombay City Improvement Trust (BIT) that wanted to ensure enough sun, air and bonding spaces for the residents of early 20th-century buildings. This regulation stipulated that the height of the buildings facing each other should be such that if you were to draw a diagonal line from the top of one building to the bottom of the other, the angle that it made with the ground would not be more than 63.5 degrees.

While the exhibition - which is on till June 25 - helped architect Rachita Vishwanath understand "why things in the city are the way they are", it left her hungry to know "what lies ahead". Padora insists the way forward is to look back. "Architects and planners must search the past for clues to build a healthier city," he said, citing the research work done by his team that threw up the kind of hidden gems that ended up shaping their affordable housing project in Karjat, which later won an award.

Replete with two sets of windows that allow for both ventilation and socialisation and with corridors bearing terrace farms, children's play areas and social gathering spaces, this project would please the arthritis-stricken elderly woman whom Padora's team had met at Borivli's shared-courtyard-boasting Bhatia Chawl. Despite owning a flat in an Andheri building that has a lift, the woman preferred to stay on the fourth floor of the chawl because: "I know that today, if I were to open my window and call for help, the entire building would come to my aid."

"You can see greed come into play here," said Vishwanath, pointing to the 'Urban Implosion' panel which included graphical sketches of post-globalisation skyscrapers such as a mushroom-shaped skyscraper in Mahim, whose seven residential floors sit awkwardly above its 10-storey parking podium - an unsubtle reminder of the 1991 Development Control Regulations (DCR) that had made parking a requirement to be accommodated in buildings.

That the very rulebooks which once sought to decongest the city and help locals combat disease in the aftermath of the 1896 plague have grown to suffocate them and make them sick, is the ironic full circle drawn by 18 graphical sketches of housing units at an ongoing exhibition titled (de)Coding Mumbai. Hardbound copies of these thick rule-books lay open on a table at the exhibition organised by sPare, the research arm of a firm headed by architect Sameep Padora, who had once deadpanned about the current Development Plan (DP) and DCR in a speech: "Don't go by their look. They are fairly light on content."

"In the hundred years that elapsed between the two global contagions, the focus of building codes has shifted from welfare to profit," said Padora, citing not only Mahul's infamous Project-Affected Persons Township (a rehabilitation project intended to house hutment dwellers displaced due to the Brihanmumbai Stormwater Disposal System) now known as a "hellhole" for its skin and respiratory conditions but also a 2018 report that attributed the spread of TB in an SRA project to the lack of ventilation and sunlight.

"Today, it really doesn't matter whether you are living in a free SRA building given by the state or a privately-developed building where an apartment costs you Rs 70 lakh; Mumbai's architecture is slowly killing us," said Padora whose team drew the idea for the exhibition from its earlier study of old structures such as Dadar Parsi Colony's non-commercial multi-family ground-plus-two buildings which sprouted from a scheme that was meant to attract people to settle in the suburbs and Dindoshi's Nagari Nivara Parishad Colony, which derives its sunlit view from the Emergency-era bylaw that "no building should be raised to a height greater than one and a half times the sum of the width of the street on which it stands and the width of the open space between the street and the building".

Another sunny bylaw relegated to housing relic is the '63.5 degree light and air plane' regulation which was part of the city's first development rules framed by a newly-minted Bombay City Improvement Trust (BIT) that wanted to ensure enough sun, air and bonding spaces for the residents of early 20th-century buildings. This regulation stipulated that the height of the buildings facing each other should be such that if you were to draw a diagonal line from the top of one building to the bottom of the other, the angle that it made with the ground would not be more than 63.5 degrees.

While the exhibition - which is on till June 25 - helped architect Rachita Vishwanath understand "why things in the city are the way they are", it left her hungry to know "what lies ahead". Padora insists the way forward is to look back. "Architects and planners must search the past for clues to build a healthier city," he said, citing the research work done by his team that threw up the kind of hidden gems that ended up shaping their affordable housing project in Karjat, which later won an award.

Replete with two sets of windows that allow for both ventilation and socialisation and with corridors bearing terrace farms, children's play areas and social gathering spaces, this project would please the arthritis-stricken elderly woman whom Padora's team had met at Borivli's shared-courtyard-boasting Bhatia Chawl. Despite owning a flat in an Andheri building that has a lift, the woman preferred to stay on the fourth floor of the chawl because: "I know that today, if I were to open my window and call for help, the entire building would come to my aid."

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

FacebookTwitterInstagramKOO APPYOUTUBE

Looking for Something?

Start a Conversation

end of article