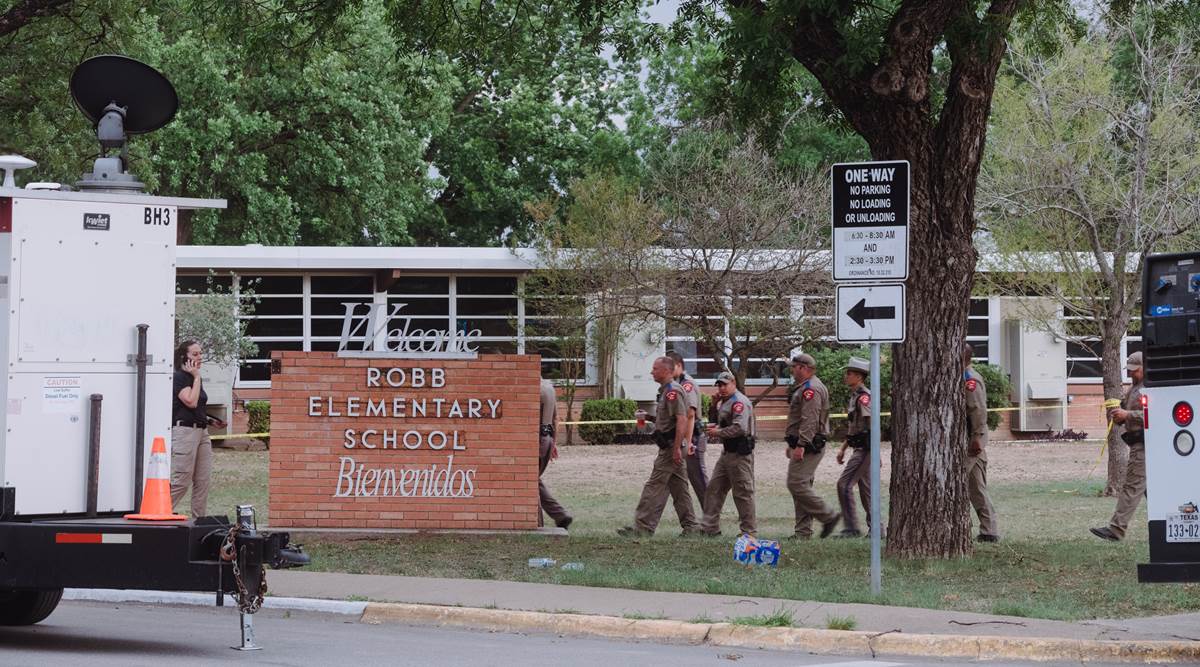

Law enforcement officials outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, following the mass shooting on May 24. (The New York Times file)

Law enforcement officials outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, following the mass shooting on May 24. (The New York Times file)It is safe to assume that every American child knows that life at school is precarious. Their parents know that nothing much can be done about this fear.

Teachers also know it. Those who want to believe that matters can be changed, return to reality after each mass shooting. A bi-polar public ethos cannot permit a change. We Indians know this, having watched TV debates where no one steps out of their assigned role. The anchor too knows her role: Keep trying to get an honest answer. In the recent Texas killings, the police added a fresh layer to earlier stories of school shootings. A group of policemen stood around for over an hour outside the classroom where children were dying. The school corridor sound proofing must be of the highest quality. Presumably, there was CCTV coverage as well. Reports say that several children had dialed the police. They were whispering into their mobile phones. The killer had streamed his action live.

Childhood, as a concept, has a short history. Cultural historians and demographers have demonstrated that as a social category, childhood has been around for no more than 300 years. Over this period, the recognition of childhood as a distinct stage of human life has gradually gained universal acceptance. The recent social history of humanity is enmeshed with the ascent of public health and universal schooling that aimed at protecting children from early death and the precipitous onslaught of adult life. The use of children as cheap labour, induction into exploitative trade and violent conflicts have proved hard to stop, but considerable progress did take place in many parts of the world.

This period of modern cultural history may already be closing. The change occurring in conditions surrounding children is pervasive and deep. It points towards a Yuganta: The End of an Epoch — the title of Iravati Karve’s monumental work on the Mahabharata. She argues that the great war marked the end of an era or yuga. Deep economic and cultural changes followed the great war depicted in the epic. People’s outlook on life and the values underpinning that outlook changed. Something of that scale is occurring in children’s life today.

Best of Express Premium

A long period that influenced parenthood and education is approaching its end. The consensus — shared by the state, industry and parents — that children need protection is dissolving. That they are a social or collective responsibility had become a common concern. The idea that childhood is not merely a biological stage of life was central to this sense of collective responsibility. The growth of knowledge in disciplines such as psychology, linguistics and anthropology enhanced the breakthrough that had already occurred in social philosophy, pointing towards the importance of childhood as a distinct and prolonged stage of life in human society. This new perspective gradually created a global consensus for child survival and welfare.

No country was immune to these pressures. The changes they brought in state policies and economics were radical. The formal recognition of children’s rights is an outcome of these historical shifts. They are based on the argument that children need protection throughout childhood extending from infancy to adolescence and early youth. As children can’t be expected to assert their rights, the state and society must guarantee that these rights are not violated. This assurance has proved hard to deliver, but now it is now facing a dire crisis. Protecting children from physical and psychological harm required a consensus that the family and the school would form an inviolable boundary around children. This consensus is no longer effective.

To begin with, the state’s role as the custodian of children’s rights has weakened. Shifts in public policy indicate a voluntary withdrawal of the state in order to create room for commercial interests directly addressing children. The state as well as the family is unable to maintain the protective ring they were empowered to maintain in some measure around childhood. The new consortium of market forces has penetrated that ring. Children can now participate in the new communication industry as consumers and also as objects or commodities of consumption. Their presence on a globally connected market of images and goods implies the availability of a massive amount of raw material for exploitation and trade. The family, the school and all other protective devices of the state have been rendered weak and vulnerable to attack in the war against childhood.

Digital communication has created an unprecedented social reality in which children can be approached without the knowledge of the adults who look after them. The sight of children playing on the street or in park-like spaces had already became a rarity as sexual crimes became more common. As children receded from public view, they became subject to oppression through the so-called social media. Their exposure to violent videos, pornography and terrorising messages is common. Tech giants remove millions of such material as part of their content moderation exercise. It is a strange ritual, for these very companies actively encourage children to participate in digital activity.

The Texas shooter live-streamed his visit to the Uvalde school. His reality show was dutifully removed. That hardly matters. As always happens, the event becomes a part of children’s awareness. No matter how tightly schools are fortified, the child’s view of the world has changed irretrievably. The propaganda of their right to be protected will, of course, continue. Insecurity and the fear of being harmed, oppressed and killed is now endemic to childhood. A social consensus against this insecurity will prove hard to build. The list of 21st century skills that schools are told to cultivate is long and ambitious. It covers thinking out of context, management of negative emotions and early induction into digital livelihood.

The writer, professor of education at University of Delhi, was director of NCERT from 2004 to 2010

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.