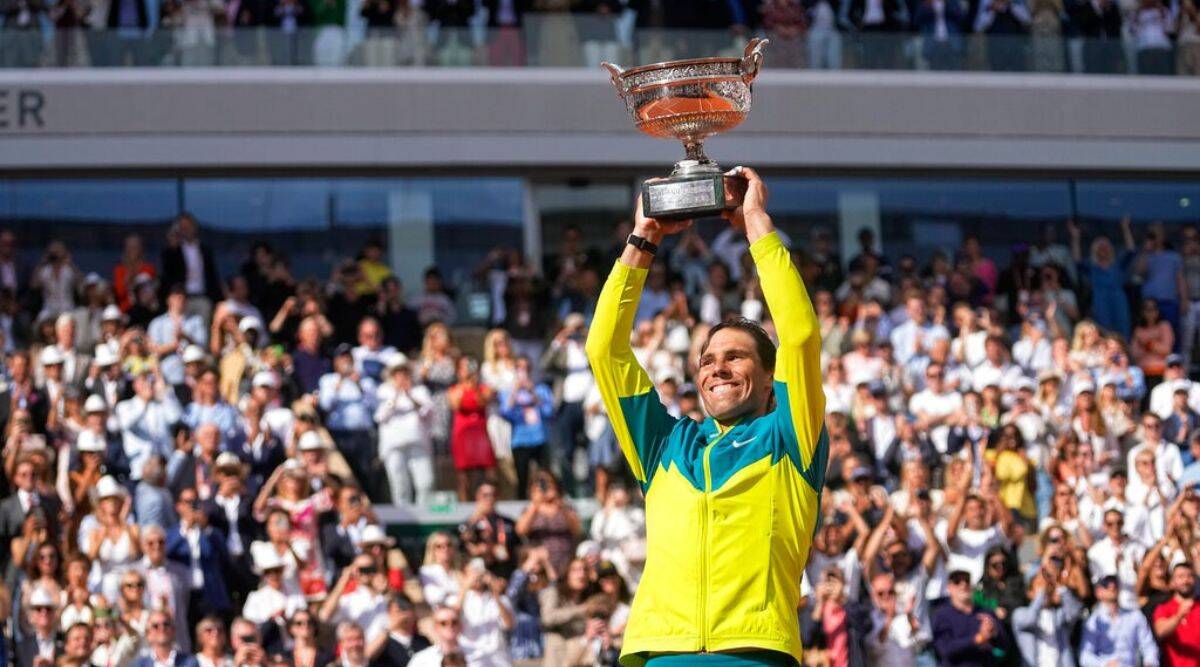

Spain's Rafael Nadal lifts the trophy after winning the final match against Norway's Casper Ruud in three sets at the French Open tennis tournament in Roland Garros stadium in Paris. (AP)

Spain's Rafael Nadal lifts the trophy after winning the final match against Norway's Casper Ruud in three sets at the French Open tennis tournament in Roland Garros stadium in Paris. (AP)His resting face looks weary as he moves slowly between points, extracting every last bit of energy from the Hulk-like body that hosts his singular soul. Rafael Nadal at 36 is now the grand old man of tennis. He stands alone as the most decorated — perhaps the greatest — tennis player in the history of the sport.

His record of 22 Grand Slam titles for a male player will not last forever, perhaps not even for a year if the freakishly talented genius from Serbia, Novak Djokovic, gets his way. But the doctrine of Rafael Nadal, the philosophy he has articulated and embodied, will live on.

The story of the intense little boy raised by a close-knit clan sharing a five-storey apartment block in Manacor, on the island of Mallorca, could be the story of any joint family in India except for one detail. The Nadal family was no ordinary gene pool. One of Rafael’s uncles, Miguel Angel played football for FC Barcelona. The other uncle Antonio “Toni” was once a top amateur tennis player who competed in the Spanish national championships and became a coach at the Manacor Tennis Club. His father Sebastian was a successful and affluent businessman.

Djokovic grew up in a war-torn Belgrade, with NATO air strikes and bomb shelters providing the backdrop for his formative years, giving him a steely-eyed warrior’s mentality that made the pressures of elite sport seem mild in comparison. Roger Federer had only his own volatile genius to overcome — with an otherwise comfortable, upper-middle-class Swiss upbringing enabled by a father employed in Basel’s thriving pharmaceutical industry.

Best of Express Premium

As a child, Nadal was scared of the dark and frightened by thunder and lightning. Till today he remains wary of dogs. Without his Uncle Toni’s tough-love tutelage the young Nadal may not have transformed into one of the most fearsome competitors in the history of all sport.

In his 2011 autobiography, Rafa: My Story, Nadal admitted to being afraid of his coach uncle Toni and dreaded having solo practice sessions with him. The domineering Toni pushed his nephew to the limit, often training him on bad courts with poor tennis balls, to teach him that winning and losing isn’t about the conditions, but about attitude and discipline. He was never allowed to celebrate successes and was constantly reminded of how few aspiring tennis players actually make it to the top. His parents and extended family often baulked at the harshness of Toni’s methods, some even called it “mental cruelty”, but they decided eventually to trust the process.

No doubt this helped forge in the young Nadal a grit and spirit that has served him well and allowed him to make the most of his other-worldly talents.

But not enough is made of Rafael Nadal’s deeply philosophical approach to life which is anachronistic in today’s world of instant gratification, endless dopamine seeking and self-promotion.

The defining theme of Nadal’s approach to life has been the need to embrace and enjoy suffering. He has a deeply internalised understanding of the vicissitudes of life, having come back repeatedly from career-threatening injuries, won and lost some of the most exhausting matches in the history of tennis, and played through constant physical pain (including at the just-concluded French Open where he has repeatedly said that the degenerative deformity in his left foot could end his career). His legendary self-control in the face of adversity on the court, aided by an equally legendary set of compulsive on-court tics and routines, have helped him manage tennis’ defining challenge — that of “resolving emergencies, one after the other” (in the words of a former physical trainer).

In the finest tradition of Buddhists, ascetics, and Stoics, Nadal has recognised that pain and loss are inevitable and they must be accepted as an integral part of life and managed with equanimity and discipline. He reminds us that the purpose of our limited time on earth is to keep engaging with life to the fullest, with maximum passion and sincerity, even though we know that life will inevitably ravage our bodies, and frequently break our hearts.

The writer is a consumer researcher

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.