Updated: June 2, 2022 7:46:10 am

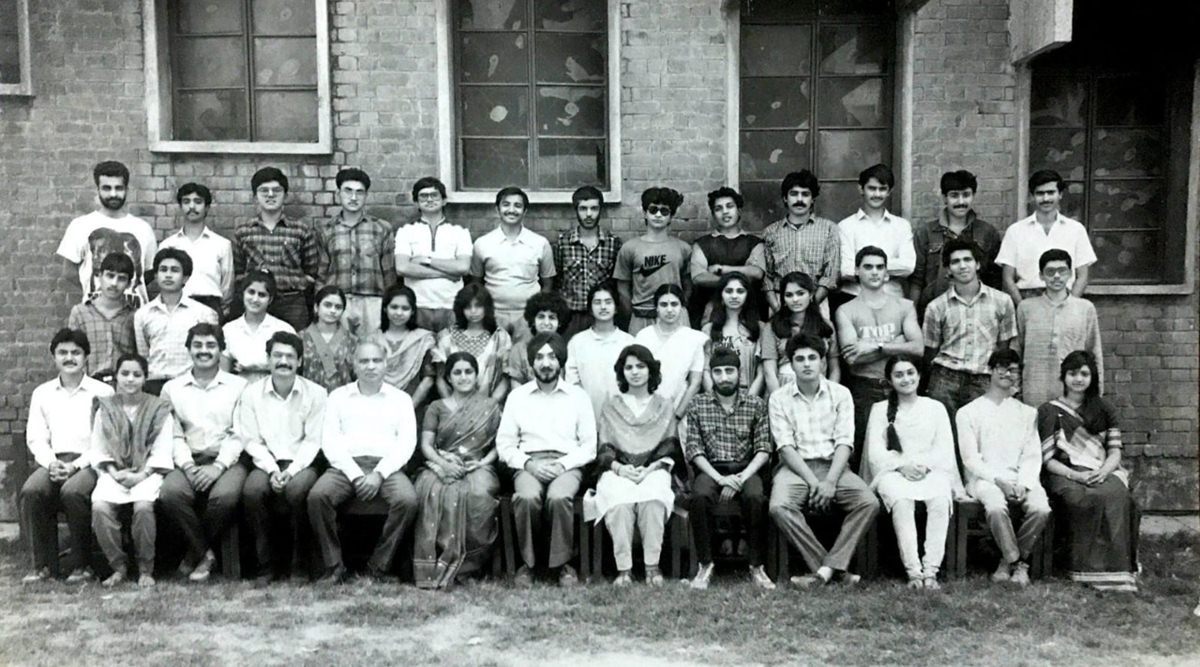

A photo of Kirori Mal College music society. KK is in the last row, wearing sunglasses. (Express Photo)

A photo of Kirori Mal College music society. KK is in the last row, wearing sunglasses. (Express Photo)In the ’80s, music was not a strong suit in Delhi University’s bouquet of extra-curricular activities. Only a few colleges had a fledgling music society. The aspiring singers and musicians at Kirori Mal College (KMC), singer KK’s alma mater, wanted to start one of their own and take their music outside the confines of the college.

Sumangala Damodaran, a third-year economics student at KMC, was one such enthusiast. In 1985, along with her friends and a physics faculty member, Sumitra Mohanty Chakrabarti, she founded the college’s music society – MUSOC. A year later, they began auditioning students for the society under the Extra-Curricular Activity (ECA) quota that enables accomplished students from different artistic fields to take admission in Delhi University. Krishnakumar Kunnath – KK’s pre-Bollywood name – was one such student.

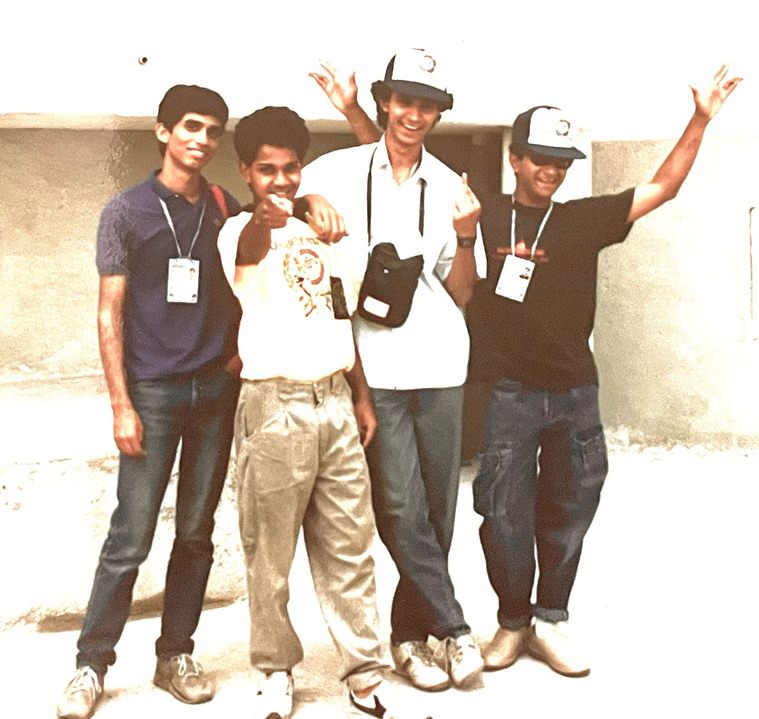

KK (standing on extreme right) was the drummer and singer for KMC’s then-band, Horizon. They represented India in the world youth festival in Pyongyang north Korea in 1989. (Express Photo)

KK (standing on extreme right) was the drummer and singer for KMC’s then-band, Horizon. They represented India in the world youth festival in Pyongyang north Korea in 1989. (Express Photo) “A diminutive young man wearing dark glasses came in and we were completely blown away by the power and feeling in his voice,” says Damodaran, now a professor of economics at Ambedkar University. “It was obvious that he would top the list for ECA admissions, but it was also his personality that was arresting.”

KK did top the ECA list. He was inducted into the college society, taking admission under the commerce course. Everybody instantly liked him. From Damodaran (“We became really good friends and sang so many duets together”) to Professor Chakrabarti, who recently retired from KMC (“He was a very dear student, often rode back home with me”) to his college bandmates, all are shaken by the singer’s death after a performance in Kolkata last night.

Best of Express Premium

The popular playback singer who lent his voice to hits like ‘Tadap Tadap’ from Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999) and ‘Aankhon Mein Teri’ from Om Shanti Om (2007) was regarded as one of the most respected singers in the Hindi music industry. But in the beginning, he was only interested in western music.

“He used to tell me, ‘Ma’am, I only listen to western music’,” says Chakrabarti. “I told him to perform Hindi music too. Years later he thanked me for that.”

A drummer and singer for KMC’s then-band, Horizon, KK dove into the college circuit and won prizes at multiple competitions. Gautam Chikermane, Horizon’s keyboardist and now vice-president of Observer Research Foundation, a policy research institute, recalls that he used to take a DTC bus every morning and reach KMC at 8:15 am for band practices in the green room. There, all six members, including KK, would practise daily to conquer the western music scene in the university.

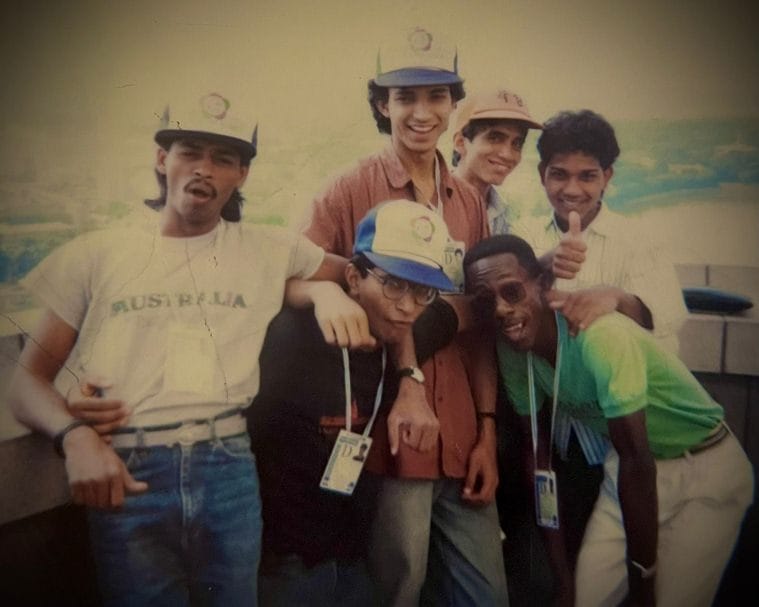

All six members of Horizon, including KK, would practice daily to conquer the western music scene in the university. (Express Photo)

All six members of Horizon, including KK, would practice daily to conquer the western music scene in the university. (Express Photo) “Once, we were performing Walk of Life by Dire Straits at Maulana Azad Medical College, and I messed up the piano intro. I started it at a very slow tempo. KK kept looking over at me from the drums and hinting to speed up, but it’s not that easy,” chuckles Chikermane. “He put his own life into every song and made it his own. He tackled diverse moods with each song he sang.”

“When we went to perform at IIT Kanpur, he happened to get a sore throat and got really discouraged,” says Sandeep Madan, Horizon’s bassist. “But we convinced him to nurse it and when we finally performed, it was 4 am. It was like nothing had gone wrong. He was amazing.”

But music was not his only love. A girl that he had known since eighth grade, Jyoti, was his other obsession – they dated through school and college and eventually married. According to Horizon’s singer and frontman, Julius Packiam, now a renowned music producer in Mumbai, KK split all his time between music and Jyoti.

KK often returned to KMC and remembered his MUSOC days fondly. (Express Photo)

KK often returned to KMC and remembered his MUSOC days fondly. (Express Photo) “After one point, every day, he was either with me in the studio recording jingles, or out with Jyoti,” says Packiam, with a laugh. “That’s all he did.”

After finishing college, KK was very serious about marrying Jyoti, says Tom Joseph, Horizon’s guitarist and KK’s schoolmate at Mount St Mary’s School, Delhi Cantonment. The couple’s parents were unsure about KK’s aspirations in music and advised him to get a more stable job. So he approached Joseph, who used to work in a company selling electronic typewriters – those became the next six (financially stable) months of his life.

“Then he married Jyoti, went to Bombay, and, of course, got his big break,” says Joseph, “but he remained a very close and dear friend. I remember a very filmi reunion in Pune when I spotted him in a car with his family, called out, and he stopped the car and came and met me. It was quite crazy. He came over for dinner that night.”

KK with his KMC teacher, Dr Sumitra Mohanty Chakrabarti. (Express Photo)

KK with his KMC teacher, Dr Sumitra Mohanty Chakrabarti. (Express Photo) “When we were invited to our college annual meet in 2004, KK called me and the other guys and said that he wanted us to play with him at the event,” says Madan. “He could’ve played with any musician he wanted, but he said, ‘No, I want to play with you guys’.”

“KK was loyal, humble, and a tremendous musician,” says Packiam. “He never even touched cigarettes or beer or even cold drinks, because he wanted to preserve his throat. He stuck to warm water. I don’t know how to process his death.”

He often returned to KMC and remembered his MUSOC days fondly. Chakrabarti says that he kept in touch with the society and used to visit her in the staff room whenever he came to the college. She recalls the night when he was performing at the college’s fest in 2013 and she had to get up from the front row mid-song and leave the venue – it was getting late and she had to drive home all the way to Gurgaon. “I found out the next day that he noticed me leaving. Apparently, he said to someone, ‘Why did Sumitra ma’am leave? Kya main itna bura gaa raha tha (Was I singing that badly)’?” she says.

Chikarmane recounts that one night, when the days of typewriter sales and hotel gigs where nobody cared about his voice were long behind KK, he came to visit him in Mumbai. They walked for a long time on Marine Drive and reminisced about their lives, failures and successes, and how divergent their paths had become now.

“He turned to me and said, ‘You know, I came here and stood exactly here on this spot and looked at these lights and wondered if Bombay would give me space’,” says Chikarmane. “It did — Bombay became Mumbai and our KK became India’s KK.”

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.