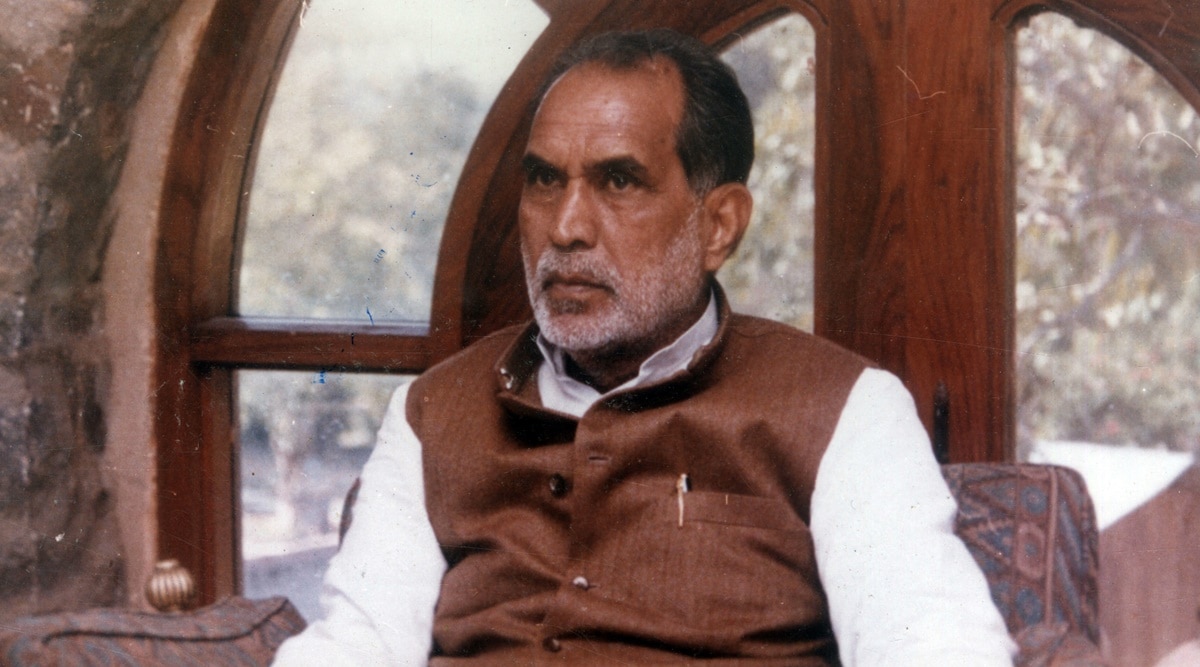

Born in 1927 in a small village in Ballia, Uttar Pradesh, Chandra Shekhar epitomised the rebellious spirit of his hometown. (Express Archive)

Born in 1927 in a small village in Ballia, Uttar Pradesh, Chandra Shekhar epitomised the rebellious spirit of his hometown. (Express Archive) On April 14, 2022, the new Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya (Prime Minster Museum) was inaugurated; incidentally, April 17 is the birthday of Chandra Shekhar, an oddball politician, an offbeat leader and an individual who, against all odds, rose to be India’s prime minister. Indeed his tenure was short, but it was not devoid of historical significance. India was staring at a precipice. At home, India faced internecine social feuds, incendiary sectarian clashes and an insolvent economy, while internationally, America and its allies battered Iraq to end its annexation of Kuwait.

Born in 1927 in a small village in Ballia, Uttar Pradesh, Chandra Shekhar epitomised the rebellious spirit of his hometown. Interestingly, Mangal Pandey, who triggered the first war of independence in 1857, was from Ballia. It was one of the three towns that declared independence during the 1942 Quit India Movement — Satara in Maharashtra and Midnapore in West Bengal were the other two. Chandra Shekhar’s rebellious streak remained throughout his life, and he remained a dissenter, always an outsider except for a few months when he occupied the highest seat of power.

Hailing from an ordinary family, Chandra Shekhar did his Master’s degree at Allahabad University and aligned himself with Acharya Narendra Dev, the doyen of the Indian socialist movement. Even from a young age, Chandra Shekhar never flinched from taking on the most powerful, pompous, and prolific personalities. As a young district level functionary at Ballia, he had a run-in with the legendary Ram Manohar Lohia, who had asked for a jeep to ferry him out of Ballia; Chandra Shekhar arrived with a car to receive his guest. A piqued Lohia then accused Chandra Shekhar of lying to him; eventually, the young leader got angry and asked Lohia to leave. In 1955, when the Socialist Party split, Chandra Shekhar chose to stay with Acharya Narendra Dev, while most of the young members gravitated towards the flamboyant and charismatic Lohia. Chandra Shekhar found Acharyaji’s sagacious, savant-like and temperate personality much to his liking, and in the 1962 assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh, Acharyaji’s faction outpolled Lohia’s party.

In Parliament, CPI leader Bhupesh Gupta enjoyed bullying the hapless members of the Praja Socialist Party (PSP). As a young Rajya Sabha member from the PSP, Chandra Shekhar had enough of Gupta’s antics and a war of words ensued; an upset Gupta called his bearded colleague a dacoit from Bhind and Morena, while Chandra Shekhar called the senior comrade a traitor for opposing the 1942 Quit India Movement. In 1964, Indira Gandhi asked Chandra Shekhar, a recent entrant to the Congress, why he had joined the party. Chandra Shekhar spoke with rare candour — either he would steer the Congress to genuine socialist ideals or break the Congress party to precipitate radical changes in the Indian political landscape. Alas, we find nobody with this kind of courage and conviction now!

While in the Congress, Chandra Shekhar took on the heavyweights, the regional satraps, and the old guards, otherwise known as “the Syndicate ”, gaining his famous epithet, “the Young Turk”. He was at the forefront during the fractious campaign for the 1969 presidential elections, an outspoken votary of bank nationalisation and a trenchant critic of the status quoists within the Congress. By 1974, Chandra Shekhar was disillusioned with Indira Gandhi for not implementing genuine, structural and comprehensive reforms to enrich India and its people. Tapping into the widespread resentment, socialist leader-turned-sarvodaya activist Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) launched protests. As the protests turned into violent clashes with the authorities, Chandrashekhar warned JP to be wary of his unruly and self-seeking associates and advised him to seek rapprochement instead of confrontation. Unnerved by the adverse court ruling on her election, Indira Gandhi declared Emergency, suspended civic rights and jailed most of the Opposition leaders. Chandra Shekhar was one of the few Congress parliamentarians to be imprisoned and one of the few political prisoners kept in solitary confinement.

In 1977, as an anti-Congress coalition under the banner of the Janata Party replaced the Congress government, Chandra Shekhar was appointed the party president, and despite his best efforts to keep the rag-tag coalition going, the Janta experiment failed. In 1980 Indira returned to power, and in 1983 Chandra Shekhar undertook a padyatra from Kanyakumari to Rajghat, an idea inspired by Gandhi’s Dandi March. Finally, it seemed Chandra Shekhar had gained a pan-Indian presence and had emerged as a credible alternative to Indira Gandhi. The tragic assassination of Indira Gandhi led to a tremendous emotional outpouring, and accordingly, the Opposition was wiped out in the subsequent election. Chandra Shekhar himself lost from Ballia.

When Rajiv Gandhi frittered away his historic mandate and got entangled in the claims of corruption, Janata Dal, yet another rag-tag coalition of the disparate and desperate group, emerged along with V P Singh, a former Rajiv loyalist. After the elections in 1989, Chandra Shekhar refused to endorse Singh for the PM’s office, instead declaring himself as a contender for prime ministership. In an ingenious but inglorious plot, Chandra Shekhar was asked to endorse Devi Lal as the leader only for Devi Lal to decline the offer and nominate V P Singh as the prime minister. An outmanoeuvred Chandra Shekhar sulked, but not for long. Within a year, he was taking oath as the prime minister with the support of 64 MPs of his own, while the bulk of support came from the Congress party.

Despite his reliance on the Congress and the fact that he had never been part of any government at any level, Chandra Shekhar went on to take some of the boldest domestic and foreign policy decisions. He took concrete steps to resolve the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute, diffused the flames of the post-Mandal agitation period, and launched new initiatives in Punjab and Assam. Once he was informed of the imminent insolvency and balance of payment crisis, he decided to barter Indian gold to save the national honour after initial inhibitions. He was the first prime minister to allow refuelling facilities to the American warplanes on Indian territories.

Within two months of Chandra Shekhar’s tenure, The Financial Times, London termed him “an uncomfortably successful prime minister”. Perturbed at his growing profile, the Congress party sought to regain control. It turned the presence of two Haryana policemen at Rajiv Gandhi’s gate into a major crisis expecting Chandra Shekhar to grovel; instead, he sent his resignation to the president, R Venkataraman. Rajiv Gandhi then sent Sharad Pawar asking Chandra Shekhar to withdraw his resignation. The man from Ballia replied: “Go back and tell him that Chandra Shekhar does not change his mind three times a day. I am not the one to stick to power at any cost. Once I decide on something, I carry it out.”

Chandra Shekhar remained a sagacious voice, even during the impassioned parliamentary speeches congratulating Atal Bihari Vajpayee for conducting the Pokhran tests. Chandra Shekhar warned the Indian government not to think of nuclear weapons as a guarantor of security and argued that if India launched a nuclear strike on Lahore, Amritsar would not survive either.

During the massive upsurge of public adulation, Indira Gandhi was exalted as the “messiah of prosperity”; at another time, Rajiv Gandhi was eulogised as the “messiah of modernity”, and V P Singh was once extolled as the “messiah of probity”. However, even during the peak of such emotional outpourings, Chandra Shekhar was one politician who remained dispassionate and refused to venerate any of them as the ultimate redeemer. The current political system seems to reward pragmatism — opportunism — instead of a commitment to ideology and conviction. In such a situation, it is not just relevant but mandatory to understand what it takes to be a leader and what distinguished Chandra Shekhar as a leader and a statesman.

Bajpai is a researcher at the School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg, Sweden and a Visiting Fellow at the Coral Bell School, Australian National University Canberra. He is co-author of Chandra Shekhar: The Last Icon of Ideological Politics

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.