Sri Lanka are going through an acute economic crisis and countries former cricketing stars are raising their voices against the ruling party. (File)

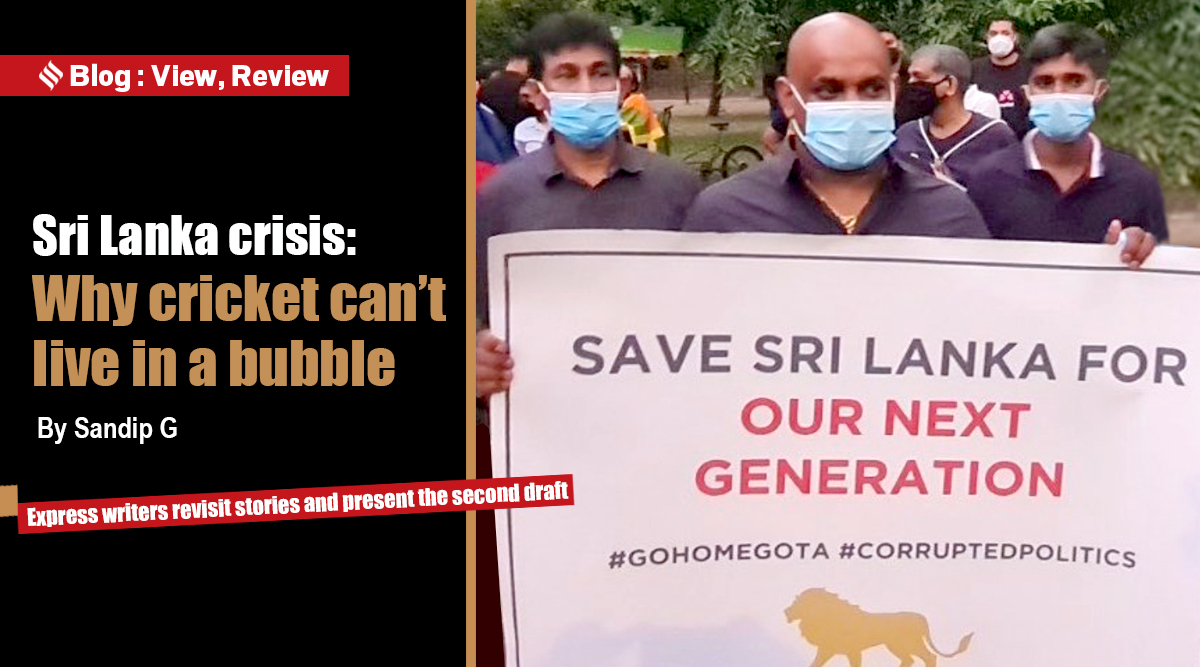

Sri Lanka are going through an acute economic crisis and countries former cricketing stars are raising their voices against the ruling party. (File) As Sri Lanka descends further into chaos and despair, some of the country’s most recognisable cricketing faces have stepped onto the streets and social media space to express their anguish and agony over the gloom that’s wrapped the island nation. The explosive former opener Sanath Jayasuriya was at the forefront of a protest march to the president’s house, brandishing a banner, “Save Sri Lanka for the next generation.” In an interview to a news agency, he grimly warns: “If the situation is not addressed properly, there will be a disaster.”

— Sanath Jayasuriya (@Sanath07) April 1, 2022

Some of his former teammates and current players too have offered strong words of support. His former captain Arjuna Ranatunga, former minister of ports and shipping, voiced deeper concerns: “I am very scared. I don’t want people to start another war, which we suffered for 30 years. Some of the politicians who are in the government are trying to show that this is created by Tamils and Muslims. By doing that, they (government) are trying to divide this country again,” he said.

When Injustice Becomes Law, Resistance Becomes Duty! – Thomas Jefferson#SriLanka #SriLankaCrisis #EnoughIsEnough pic.twitter.com/Qx0ZOHDyg4

— Arjuna Ranatunga (@ArjunaRanatunga) April 5, 2022

Even the usually social-media-shy Mahela Jayawardene and Lasith Malinga too penned touching notes on Twitter and Instagram. So have some of them watching the anarchy unfold from Mumbai, the leg-spinner Wanindu Hasaranga and big-hitting batsman Bhanuka Rajapaska (unrelated to the Rajapaksas that govern the country and whose ineptness and mismanagement are widely considered the reasons for the crisis they are wading through).

Their lives might not change dramatically. They have made their careers and shall continue to earn paychecks in dollars. So would a clutch of others plying in various franchise leagues across the world or have been regulars in the national side. But not so with the rest, those playing in the clubs, in the schools, or those wanting to be cricketers, When a country becomes embroiled in a shuddering crisis, be it cultural, political, social or economical, when there is an acute shortage for everything from fuel to food, milk to vegetables, sport becomes an easily dispensable luxury.

— Mahela Jayawardena (@MahelaJay) April 3, 2022

Sports thriving in war or catastrophe is a grand but vacuous illusion, a narrative spun by those that have never seen a war or been through a crisis. The rise of cricket in Afghanistan is often cited as an example, but it’s an exceptional exception, and for all their rapid progress, cricket is still in its infancy in Afghanistan. Cricket, or any sport, has no power to stop a war, or fill the stomach, or bring peace, or pay off debts. In the present milieu, it could not even offer an escape from the bruising realities that the average Sri Lankan encounters.

— Bhanuka Rajapaksa (@BhanukaRajapak3) April 3, 2022

In a country where the school exams had to be cancelled because of paper shortage, where they have to stand in a queue from dusk to dawn to get ration, where forget milk, even milk powder is running short, what balm does cricket offer? How would a young, aspiring cricketer sidestep the crisis and focus solely on his cricket? How could he be immune to his environment and build a career? What of his nutrition, motivation, mental state? Could he be thinking of cricket or the next meal? Modern sports and sportsmen need a conducive background to flourish—there are outliers that flout patterns, but in general, sport is not immune to socio-political developments around it.

The pangs of this downturn would be felt more harshly by those playing for the country’s clubs, its schools and the cricket academies. The young and the aspiring. That the Sri Lankan cricket board is not recession-proof would further make their lives harder and future bleaker.

The board, like the country, is not a model in governance. Players are perennially disgruntled over their salaries; the revolting players are duly banned; bribery, nepotism and favouritism hardly register a shock. They have not yet recovered from the losses it incurred in rebuilding the stadiums for the 2011 World Cup, which landed them a debt of 15 million dollars. In 2015, the debt had soared to 70 million dollars, according to local newspapers. The Lanka Premier League offered a ray of hope, but in the prevailing circumstances, its immediate future looks bleak. As would the future tournaments – they are scheduled to host the Asia Cup later this year, and bilateral series, the chief income of the board. The whistle-stop white-ball series between India and Sri Lanka last year had made the board richer by 6 million USD.

To sustain, the board would cut corners. More people would lose their jobs, more would endure salary cuts and the funds to grass-root and youth development would be reduced or stopped altogether. Second-tier circuits are the most susceptible to collapse if sponsorships further fade. Disillusionment would waft across the island.

I would’ve joined this crucial movement if I wasn’t in Bangladesh right now. But I can’t stress enough how proud I am of these brave Sri Lankans #PowerToThePeople pic.twitter.com/fTtrr9N6gt

— Upul Tharanga (@upultharanga44) April 4, 2022

It does not help that Sri Lankan cricketing itself is careening treacherously through the edge of the precipice–their glory days are long gone and they are but a pale shadow of the entertainers they once were–the national crisis could shove them down the slope to the abyss of oblivion. A national crisis would impact the most robust of economies, and for the not-so-prosperous, it could push them to the darkest of days, the hardest of times.

Inevitably, the crisis would have a direct impact on sponsorship. The national team might continue finding a sponsor, so would big matches. But it would not be the case for local tournaments, or for local schools or academies or clubs. Many of them could shut shop; many of them would reel; many of them would ignore the game. In these difficult times, a sport is the least significant of casualties. And without adequate support, encouragement and guidance, the supply line to the national line would be snapped.

Cricket would not die in the country. Its roots run so deep; it throbs their subconscious. But it would survive as a painful monument of the crisis—as a skeleton, as shambles, like it is now in Zimbabwe. Turmoil struck Zimbabwean cricket just when it seemed to come of age, just when it seemed that a genuine cricketing nation was rising. A host of players, some of their best players, left the country after the growing influence of ministers in the affairs of the cricket board. “We felt we had no future in the country. We would have been killed, or we would have been bankrupt. We lost our land and our dignity. We could not lose more,” former batsman Murray Goodwin had once told this newspaper.

Goodwin moved to Perth to play Shield cricket and later switched to real estate. Henry Olonga, who wore black armbands during a World Cup match to mourn “the death of democracy” moved to Adelaide and became an opera singer. Andy Flower shifted to England and later became England’s coach while Tatenda Taibu swapped his gloves for The Bible. He became a pastor in England. The nucleus of a competitive team was thus disassembled. Years later, the ICC banned Zimbabwe. They were reintegrated, but they are but a walking shadow of what they once were. The political crisis in Zimbabwe soon escalated into an economic one, under which the nation is still tottering. If it were to happen to Sri Lankan cricket, it would be even more cruel.

There are other examples too—economic crisis impeded once thriving football cultures in Zambia, Nigeria and Greece. The civil war eliminated Syrian football, once full of promise.

Sri Lanka has weathered many storms in the past—the prolonged civil war, the 2004 Tsunami, and more recently, the Easter bombings among others. But many fear the most devastating of all could be the economic unrest that’s making the island in the shape of a tear-drop shed more tears. Cricket could be the least foremost of Sri Lanka’s concerns, when there is an acute shortage for food and fuel, but a great cricketing culture could be lost forever, sunk into the bowels of the Indian Ocean.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.