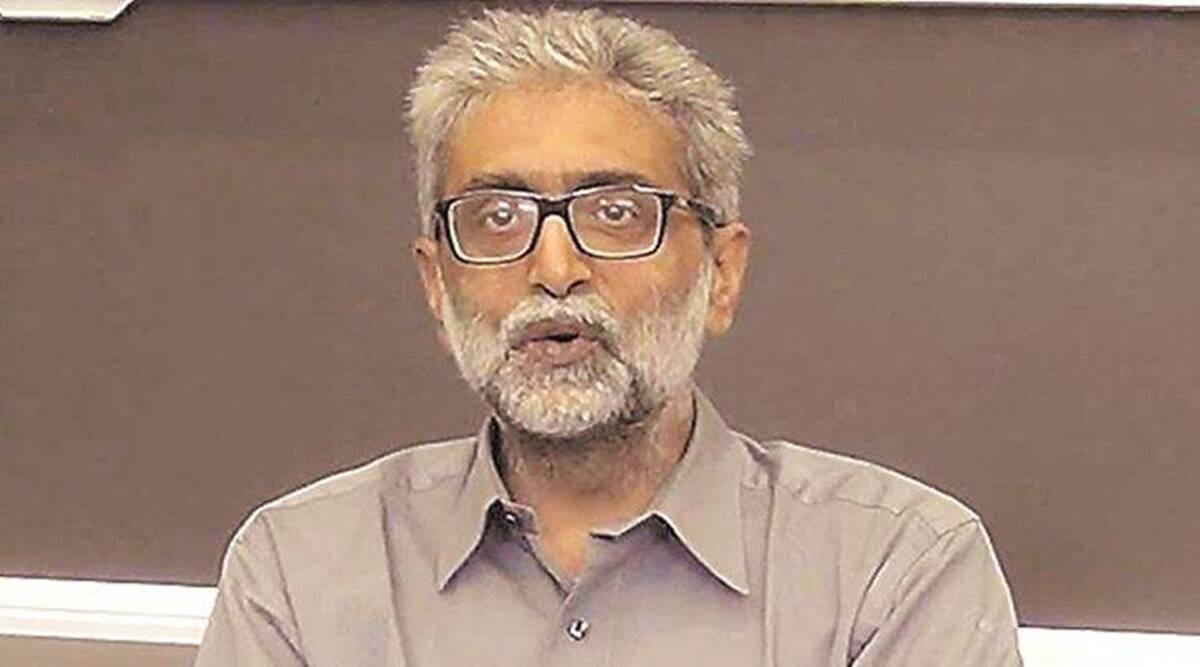

Gautam Navlakha (File)

Gautam Navlakha (File) Gautam Navlakha, the veteran human rights activist accused in the Elgaar Parishad case, had requested a copy of The World of Jeeves and Wooster. It was initially denied as a “security risk” by Taloja Jail authorities, a decision the Bombay HC termed “comical”.

What’s truly comical is that it’s Wodehouse. Even Indian fairy tales like Thakurmar Jhuli pack more subversion in them than the fading world of unflappable British valets, battle-axe aunts, and prize pigs. Even more ironic is that Wodehouse liked to claim he was apolitical. He was interned in a prison camp because he happened to be living in France when Germans invaded. When the Nazis released him, they asked him to broadcast some amusing stories about prison life. Wodehouse thought that was a plum idea and was baffled why the English were not amused.

Wodehouse remains a jolly good fellow even if the world he depicted feels archaic. Some might be surprised that Navlakha even wanted to read him in 2022. But as writer Evelyn Waugh presciently told the BBC in 1961, Wodehouse’s “idyllic world can never stale” because he continues to “release future generations from captivity that may be more irksome than our own”. Little did Waugh realise, in Navlakha’s case that captivity would be literal not metaphorical.

His enduring appeal to Indians can feel like a mysterious colonial hangover. Shashi Tharoor, who founded the PG Wodehouse Society at St. Stephen’s College and has read all 95 of his books, has written about how shocked he was when at a panel in England, the young moderator asked: “So how do you pronounce it — Woad-house or Wood-house?” But in India he has never gone out of fashion. However it’s not just nostalgia for the times of sahibs and memsahibs. Wodehouse’s appeal is that he appears untainted by colonial condescension, nor affected by post-colonial guilt. He is a guiltless pleasure. His books still serve as a masterclass in wordplay, effortless marrying the hifalutin with the silly as he tells us someone looks careworn “like a Borgia who suddenly remembered that he has forgotten to shove cyanide in the consommé, and the dinner gong is due any moment”.

That soufflé silliness that permeates Wodehouse has prevented him from being taken seriously by scholars. Inadvertently, the Maharashtra jail authorities might have given him a gravitas that eluded him in life. But it’s also true that the mischievous wit of Wodehouse feels out-of-sync in a country where stand-up comics can be picked up by the police for jokes they might crack. As comedian Anuvab Pal once said, in India, “the first question in a comedy panel is ‘what will you get in trouble for?’”. So it’s hardly surprising that a book by a humorist raised red flags with prison authorities.

Yet this flap about Wodehouse should not distract us from the real issue at hand. Navlakha, a man in his seventies, was also denied his spectacles and a chair for a bad back. Father Stan Swamy, a Parkinson’s patient, had to fight for a straw and sipper because he could not hold a glass. Lawyer Sudha Bharadwaj had to get a special NIA court order to be allowed five books a month. All of them, guilty or innocent, are entitled to their day in court. Until then, the larger issue is their treatment under incarceration and that, unlike Wodehouse, is no laughing matter.

In 1921, Gandhi’s follower Madeleine Slade aka Mira Behn was incarcerated in Bombay’s Arthur Road Jail. As recounted by Ramachandra Guha in Rebels Against the Raj, she wrote that the sum total of treatment of women prisoners in British jails is “obviously designed to try and crush our spirit”.

In light of that, this exchange between Wooster and Jeeves is more grim than droll.

‘Good evening, Jeeves.’

‘Good morning, sir.’

This surprised me. ‘Is it morning?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Are you sure? It seems very dark outside.’

(The writer is a novelist and the author of Don’t Let Him Know)

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.