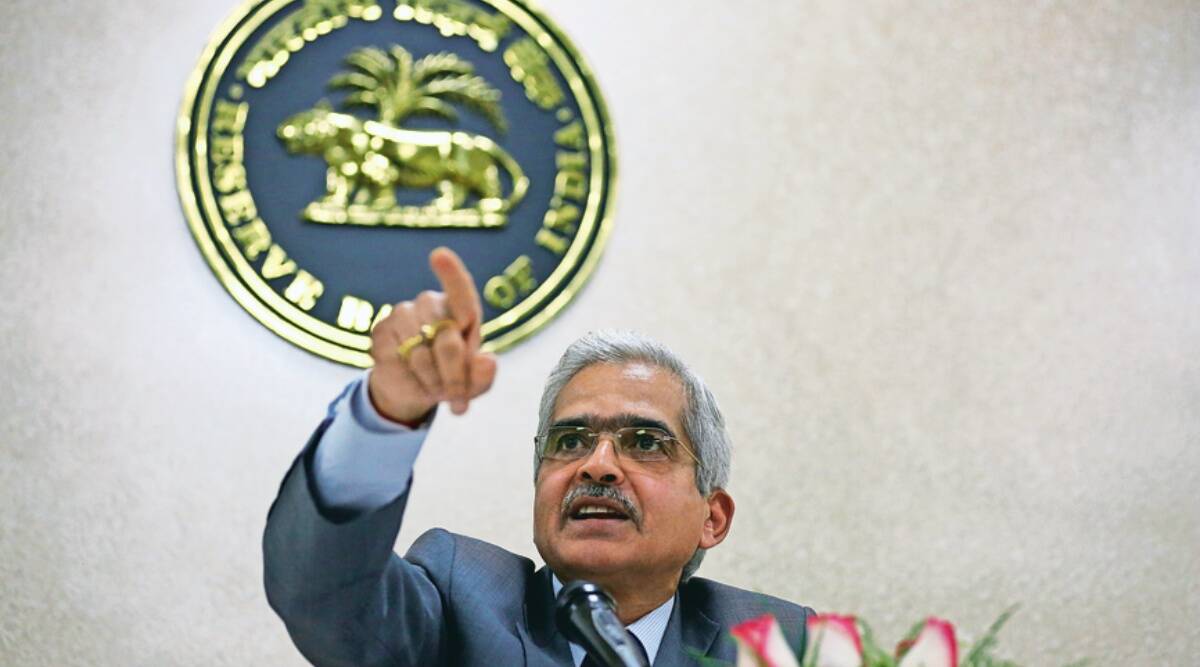

Shaktikanta Das Governor, Reserve Bank of India (File)

Shaktikanta Das Governor, Reserve Bank of India (File) The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) gave a surprise, with a formal start to policy normalisation. This was contrary to the predominant market expectations of a hold. The RBI reinforced the de facto normalisation, which had already started in November 2021. The Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) corridor was narrowed back to the conventional 0.25 percentage points from the earlier extraordinary pandemic widening in late March 2020. But with a twist. The cap of the erstwhile corridor was the repo rate and the floor was the reverse repo. Now, while the repo rate was held at 4.0 per cent and the latter at 3.35 per cent, the floor of the corridor was increased by 0.4 percentage points from 3.35 per cent. The de facto operative floor is now the rate of the new Standing Deposit Facility (SDF) at 3.75 per cent.

There was also a change in the monetary policy orientation, of which the stance is one component. The priority for monetary policy now is inflation, growth and financial stability, in that order. This is a reversal of the earlier priority. This has entailed a change in guidance on the policy stance as well. While the MPC voted unanimously to remain accommodative, in a change of language, the focus would now be on “withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that (CPI) inflation remains within the target (of 4 per cent +/- 2 per cent) going forward”. Remember, the RBI had become a (flexible) inflation-targeting central bank since FY17, whose primary objective is price stability, that is, inflation management.

These measures are still mostly normalising policy from the extraordinarily accommodative crisis measures back to pre-Covid levels. Actual policy tightening will begin with the first hike in the policy repo rate, which we now think will start sooner than our earlier expectation of around October 2022. In the interim, policy actions will focus on the management of system liquidity, which is currently at an (uncomfortable) surplus of Rs 8 lakh crore.

The likely reasoning for the unexpected tightening is as follows. Despite uncertainty over growth impulses and demand concentrated at the upper-income level households, inflation has increasingly emerged as a big concern. Unlike previous episodes of high crude oil prices, prices are now elevated across the board — gas, metals, minerals, commodities, food, gold, etc. This is likely to add to sustained price pressures, even after a cessation of hostilities. The RBI revised its FY23 CPI inflation forecast from 4.5 per cent (with balanced risks) in early February to 5.7 per cent, with a caution that extreme volatility and uncertainty make forecasting fraught with risk. Persisting high inflation increasingly suggests that consumer demand might actually be stronger than earlier anticipated. In addition, the RBI’s CPI inflation forecasts for the first two quarters of FY23 are 6.3 per cent and 5.8 per cent. Given that inflation is likely to average 6.1 per cent in Q4 of FY22, this increases the risk of inflation remaining above the 6 per cent upper target for three consecutive quarters, necessitating an explanation to the government by the MPC. One comforting aspect of this scenario is that household inflation expectations remain anchored, with the median of three months to one year ahead expectations (as of March ’22) rising by only 0.1 percentage points from the earlier January readings.

On demand conditions, the RBI scaled-down the FY23 real GDP growth projection to 7.2 per cent (from 7.8 per cent), indicating that a combination of continuing supply dislocations, slowing global economy and trade, high prices and financial markets volatility are likely to take a toll. Yet, there remains a point of ambiguity. RBI surveys indicate that manufacturing capacity utilisation (CU) was 72.4 per cent as of December 2021, up from 68 per cent in September. Despite the mild restrictions in Q4 FY22, this is likely to have gone up even further. Anecdotal evidence supports a narrative of tight capacities in many manufacturing sectors. One possible reconciliation with modest GDP growth is continuing weakness in services, which is also borne out by channel checks. Certainly, continuing high inflation is likely to lead to some demand destruction, which will act as, in economist parlance, an automatic stabiliser. A relatively loose fiscal policy is likely to offset some of this reduced demand, particularly with continuing subsidies to lower-income households.

The third priority is financial stability. This has multiple dimensions – interest and foreign exchange rates, market volatility, banking sector asset stress, and so on. An important objective for the RBI is the management of money supply and system liquidity. In a rising rate cycle, with a large borrowing programme of the Centre and state governments, interest rates on sovereign bonds are likely to increase without a measure of support from the RBI through Open Market Operations (OMOs). This will entail injecting more liquidity into an already large surplus, which might add to inflationary pressures. The introduction of the overnight Standing Deposit Facility (SDF) was a significant measure in this context. Unlike the reverse repo facility, this is an uncollateralised tool for absorbing surplus liquidity. The RBI will not need to give banks government bonds as collateral against the funds they deposit. This is thus a more flexible instrument should a shortage of government bonds in RBI holdings actually transpire under some eventuality, say the need to absorb large capital inflows post a bond index inclusion.

What are the implications of monetary policy tightening? First, interest rates will begin to increase but, for bank borrowers, this is likely to be a very gradual process. For corporates and other wholesale borrowers, who also borrow from bond markets, this increase is likely to be faster as the surplus system liquidity is gradually drained. Interest rates on bank credit will begin to rise faster once the repo rate hikes begin, since around 40 per cent of bank loans are now linked to external benchmarks (like the repo rate). How this is likely to affect demand for credit is uncertain, given the capex push of the government, some revival of private sector investment and likely continuing demand for housing.

What might be the sequence for continuing tightening? Any exit strategy following periods of extraordinary countercyclical responses presents difficult choices for monetary policy normalisation. This cycle will present a particularly difficult mix of economic and financial trade-offs, but RBI has demonstrated the ability to innovatively use the multiple instruments at its disposal to ensure an orderly transition.

(The writer is executive vice-president and chief economist, Axis Bank. Views are personal)

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.