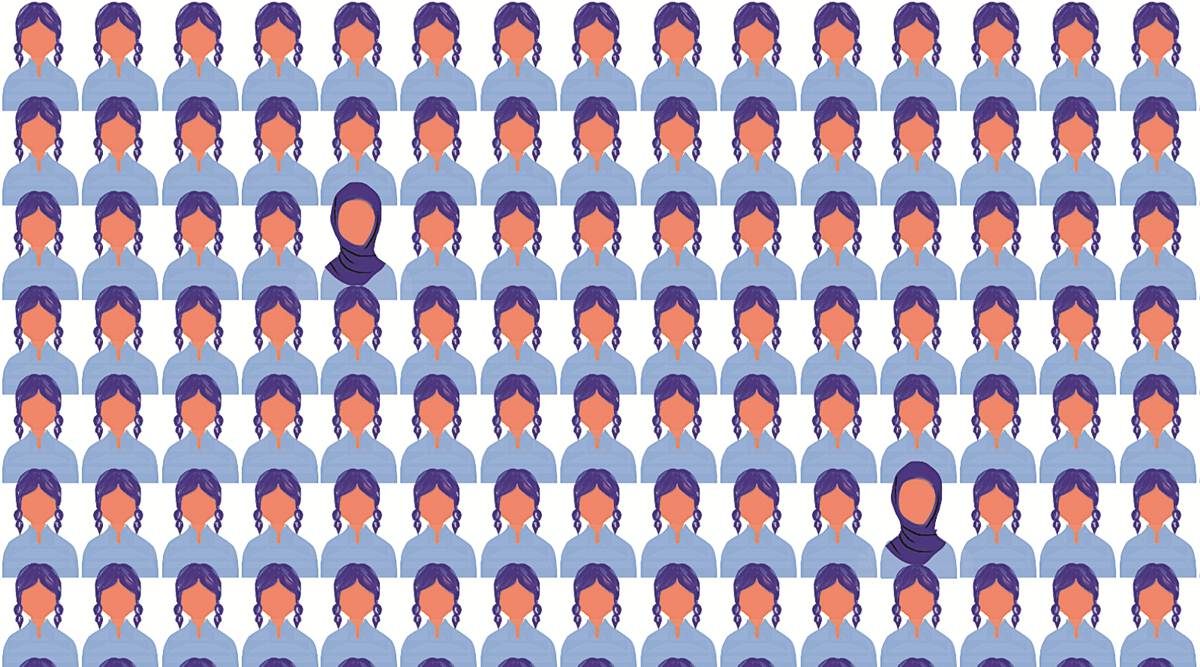

The KHC cites a passage from my book,The Future of Human Rights, which reminds us that freedom of conscience precedes the right to religion. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

The KHC cites a passage from my book,The Future of Human Rights, which reminds us that freedom of conscience precedes the right to religion. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar) The entire future of the Indian judicial process is being put at stake in the “faith vs Constitution” controversy. The primary task of constitutional politics is to transmute a partisan controversy into a reasoned public debate. Allegations of “judicial overreach” greet any adjudicative “reasonable accommodation”, especially when it engages the constitutional right to education under Article 21-A.

The Karnataka High Court (KHC) recently advanced the doctrine of “qualified public space” in the hijab case – something not usually noticed in the critical discourse engaging with the essential practice of religion or the rights to dignity, culture, and privacy. Even when it remains a contentious doctrine, it is worthy of emphasis that the KHC allows wearing hijab on the school campus or other public spaces, while disallowing the hijab in classrooms. This judicial feat, however, is marred by disallowing even “hijab of structure and colour that suit to the prescribed dress code”. The KHC is determined to prevent “non-uniformity in the matter of uniforms”, and an undesirable “sense of ‘social separateness”.

Why so, especially when empirical studies demonstrating this “separateness” are scarce? Intuitively, it invokes the fundamental duty of all citizens to ensure that “common brotherhood” is not affected by the hijab. But why are other religious symbols allowed (wearing kumkum, turban, beard, tilak, or cross) — whether as religious essentials or cultural preferences?

Identities are both ascribed and fluid. But I learnt from Shah Bano (as interviewed by Dr Seema Sakhare) that she was not a “napak aurat” (an impious woman) when she affirmed both her religious identity and deployed the modern law as a means to secure the rights of an Indian Muslim woman citizen. So did about 50,000 Muslim women who signed a petition to the prime minister demanding a law that would abolish instant triple talaq. She also taught me about the processes or practices of identification and there exist at least three related human rights: The human right to have an identity, to acquire different identities, and to manage conflicts of identity.

The KHC cites a passage from my book,The Future of Human Rights, which reminds us that freedom of conscience precedes the right to religion. The Constitution recognises that each citizen has a right to a moral faculty called conscience, which helps to choose or change a religion, or renounce all religion. Conscientious choices do not lead to separateness. Identity only makes social sense when difference is recognised and respected. Article 51-A enjoins as a fundamental duty of all citizens to “value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture”. A composite culture is a “culture of many cultures”, not a “culture of no cultures”.

The KHC does not have much to do with practices “derogatory to the dignity of women”. And, intriguingly, it remains silent on the duty to “value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture”.

Should all the new rights to dignity, privacy, and the right to be and to remain different be trumped by a single-minded insistence on the integrity of a uniform? May the ends of a uniform not have been met equally by other strategies of imparting learning? Do other ways exist to foster “engagement” with the “foundational” trinitarian values — dignity, equality, and liberty? And is respect for dress as symbolic speech not enshrined in the right to free speech and expression?

The hijab controversy ought not to make further make cracks in constitutionalism. Does suffering the nightmare of partisan constitutionalism, serving propaganda and power in competitive quasi-liberal politics, presage our common futures? Or does the struggle to realise the dreams of equality and constitutional plurality (equality of all) offer a better alternative?

The Supreme Court should strive to extricate itself from the crossfire of internal and external dissent since the Sabarimala decision. A resultant piquant situation has led two CJIs — CJI Rajan Gogoi (November 14, 2019) and S A Bobde (on January 13, 2020) — to make a reference to a larger Bench, now to comprise nine judges.

The Court has now to consider not just the Sabrimala review, constitutionality of Dawoodi Bohra female genital mutilation practices, the entry of non-Parsi women (married inter-faith) into the fire temple, and of Muslim women into mosques but also the larger questions about the scope and ambit of religious

freedom. Unsurprisingly, this encyclopedic matter is still to be heard.

If the KHC decision were upheld now, would it necessarily preempt some issues before the SCI larger Bench? How may the apex judicial outcomes on the ambit of Article 25 affect the KHC decision? How adroitly such questions are managed will carry a fateful impact on law, power, and justice.

Any credible threshold evidence that certain organisations promote an agenda for separation threatening the roots of public order, and unity and integrity of India, merits strict and swift judicial scrutiny. So do the chilling effects of the misuse of the law on freedom of speech and dissent and wrongful prosecutions.

The KHC was right in hoping that such allegations will be met swiftly. But prevention of the unconscionable othering of Indian citizens by governance cultures and the demonising of protesting publics should be high on any governance agenda. And civil society intolerance must pause to give the right of way to priorities of just social peace.

Constitutional governance entails rectitude, and responsibility, in the exercise of power. We should recall what Justice J Chelameswar [para 39, Puttaswamy case] insightfully said: “The choice of appearance and apparel are also aspects of the rights of privacy. The freedom of certain groups of subjects to determine their appearance and apparel are protected” and “need not necessarily be based on religious beliefs falling under Article 25.”

The writer is professor of law Emeritus, University of Warwick, and former vice-chancellor of Universities of South Gujarat and Delhi

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.