In 1950, Joshi settled down in Pune, which had a very knowledgeable classical music milieu that appealed to several top musicians.

In 1950, Joshi settled down in Pune, which had a very knowledgeable classical music milieu that appealed to several top musicians. In January 1946, the Poona Music Club organised a major concert in Hirabaug to celebrate the 60th birthday of the living legend Sawai Gandharva; but the event would become a landmark in the history of India’s classical music because of another musician, Gandharva’s 24-year-old disciple Bhimsen Joshi.

Joshi, who had become popular by singing for the All India Radio, was assigned the opening slot in the concert because he was quite junior. “This was his debut concert on a public platform… he was a little anxious,” writes Kasturi Paigude Rane in the book, Pt Bhimsen Joshi. But, the vocalist “mesmerised the listeners and put them in a trance… the overjoyed guru was extremely proud”. Joshi, who would become one of India’s greatest musicians, would say that the concert changed the course of his life and “propelled him to fame in the true sense of the term”.

February 4 marked the birth centenary of Joshi, who passed away in 2011 at the age of 88 in Pune. “A lot of people don’t know that he was born in Gadag in Dharwad, Karnataka, which was a part of Bombay Presidency, in 1922 and that his mother tongue was Kannada. He learnt Marathi later. At home, he enjoyed bhakri, which is popular in northern Karnataka, as well as gur-poli that was made during Sankrant, though he was strict about food and rarely ate more than twice a day,” says Joshi’s daughter Subhada Mulgund, who used to accompany him on the tanpura.

Joshi’s father Gururaj Joshi was a teacher who had graduated from Fergusson College in Pune. The city would later feature more prominently in the vocalist’s life. The first time he had set foot in Pune was as a young runaway who had set out to find a guru in Gwalior but boarded the wrong train at Bijapur station. “He knew he had to get to Gwalior somehow but was not sure which route would get him there. Hence, he took a train to Pune and travelled without a ticket again. He managed to entertain his fellow passengers and the ticket checkers with his music and was able to get to Pune without being stopped by the railway staff at the exit point,” writes Rane. Without money or food, Joshi had wandered the streets of Pune and tried to make money by singing.

After travelling through large parts of India, he found his guru, Gandharva, and lived in the village next to his own in Karnataka. He trained with Gandharva till 1940 and is counted among the latter’s foremost disciples.

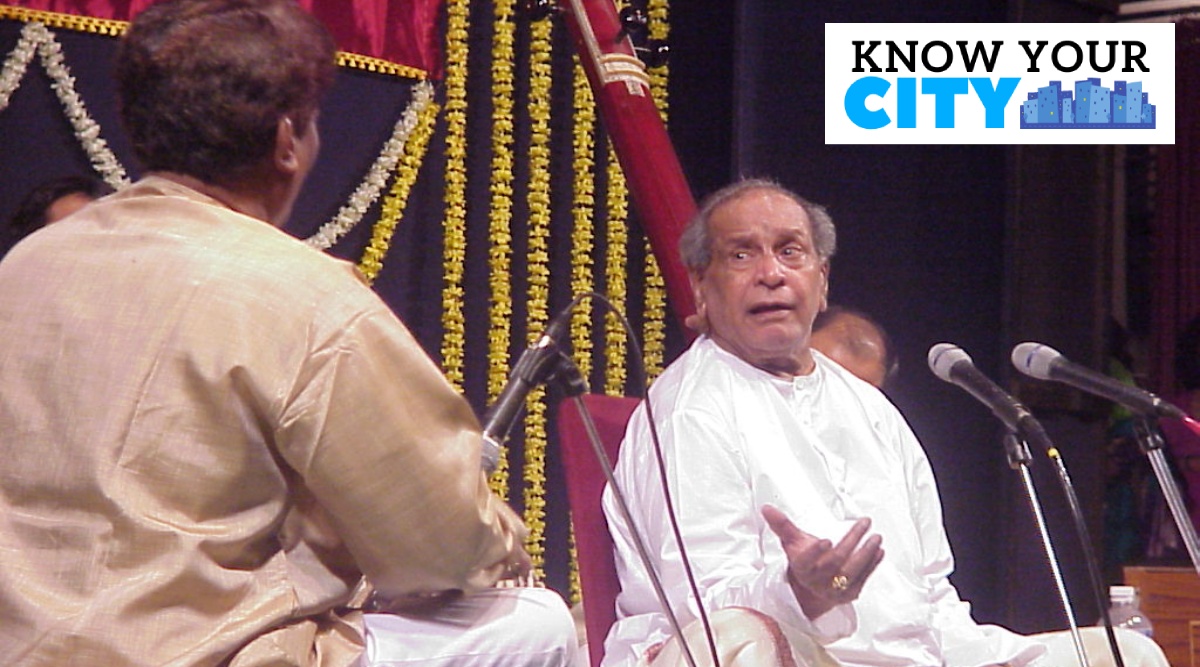

Joshi with his son Shrinivas. (Films division)

Joshi with his son Shrinivas. (Films division) In 1950, Joshi settled down in Pune, which had a very knowledgeable classical music milieu that appealed to several top musicians. “I must have been around four years old when I used to go with the rest of the family to my father’s concerts. In Pune, in those days, concerts would start after 9 pm and carry on all night, so I used to sleep. My sleep used to break because of the resounding applause that followed my father’s performances. I remember that everybody would be very happy and people used to surround him. My father used to look different after concerts as there used to be a glow on his face,” says Mulgund.

It was also the time when the Ganeshotsav in Pune used to feature classical music performances by organisations such as the ones in Mandai and Raasta Peth. Hundreds of people used to come to these performances in an era when entertainment options were few and traffic congestion almost unheard of. At the recent Pune International Film Festival, playwright Satish Alekar pointed out that Joshi could be at a prestigious venue or on the streets of Pune during Ganeshotsav, but have the same clarity, dedication and surrender to the Kirana gharana.

“He used to have mehfils in venues that do not exist anymore or, if they do, haven’t held a musical programme for years as the sensibilities of the city have changed,” says Mulgund. Some spaces have grown in stature, such as the Bal Gandharva Rang Mandir. With PL Deshpande as one of its moving forces, the major auditorium was inaugurated in 1968 with concerts by maestros such as Vasantrao Deshpande, Sudhir Phadke and Joshi.

The family lived in rented two-bedroom apartments near Tilak Road and, then at Rambaug Colony near Lal Bahadur Shastri Road. “Artistes did not make as much money as they do today, when even an up-and-coming musician can charge a hefty amount. Ours was a simple, middle-class family, where music was very important. My mother was his shishya and would sit with her music morning and evening, as soon as the housework was complete. Musicians and music lovers would drop in all the time. I remember Nirmala Devi, mother of the actor Govinda, as well as Ustad Vilayat Khan sahab, Pt Jasraj, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, Pt Ravi Shankar and Ustad Zakir Hussain visiting our two bedroom-home,” says Mulgund. In 1981, the family moved to the bungalow, Kala Shree.

Joshi with his family (Films Division)

Joshi with his family (Films Division) Jayant Joshi, the maestro’s eldest son, says: “Music was the reason for his existence. He used to say that a singer should channel his energy into singing. I have been to several music conferences with him and, once a performance was over, he used to get back. There was no wastage of time exploring cities as, for that, he used to organise different trips. He didn’t like to discuss or analyse theories of music as he used to feel that you should show your knowledge through your performance.”

On September 28, 1952, a little more than two weeks after the death of Gandharva, a group of his disciples including Gangubai Hangal and Joshi, decided to express their bereavement through music. They held a private concert and, the following year, a bigger public event in memory of their guru. The ritual was repeated every year and began to draw esteemed musicians and devoted listeners from across the country to Pune. It was the only event of its kind in the city.

Today, the Sawai Gandharva Music Festival has grown to be one of the country’s major concert-series and seals Pune’s place among the centres of Indian classical music. A lot of the musicians stayed at Joshi’s home during the festival as the city did not have many hotels at the time. “There was a good hotel called Poonam in Deccan, where some musicians stayed, but the music world was informal. Artistes travelled by train and were not motivated by money. It was a good time because we could meet everybody and talk to them. Today, everything is formal,” says Mulgund.

Performances were mostly for three nights and, on the second day, musicians filled Joshi’s home. Shrinivas Joshi, his son and disciple, remembers, “There was a time my mother was not able to attend a session because she wasn’t well. Pt Jasraj was scheduled to perform. When he came to know that she had not attended, he came the next day to perform for my mother at our home.”

Pandit Bhimsen Joshi at dinner table with family (Credit Films Division)

Pandit Bhimsen Joshi at dinner table with family (Credit Films Division) Joshi also indulged his love for wheels, buying second-hand American cars such as Buick and, as the price of petrol rose in the 1970s, a Fiat and then a Maruti 800. He enjoyed driving and took his family and friends on long road trips, especially driving from Pune to Kashmir in 1965 and then from Pune to Kanyakumari in 1966. At home, he was an expert carrom player with the children and friends who dropped in.

Later, he became busy performing across the country and the world as invitations poured in. One of the busiest artists in the country, he would prefer to rest once he was home. “For him, sleep was the solution to every problem. Sometimes, it happened that he did not sleep for three nights because of concerts. After coming back home, he used to sleep. He was a deep sleeper, could sleep whenever he wanted,” says Jayant. Mulgund recalls that Joshi would have one of his greatest qualities, of concentration, even when watching television. “If he were watching NatGeo, Animal Planet or cricket, he would be so immersed that he wouldn’t hear us when we spoke. It was my mother who looked after the family as well as supported my father,” says Mulgund.

Joshi had met Vatsala during a concert in Aurangabad, when he was 19 and she was a 13-year-old interested in music. “They were introduced to each other and, after some time, decided that they wanted to get married but my mother’s father opposed this because ‘the boy belonged to an orthodox family of Karnataka’. Later, a play was being staged, titled Bhagyashree, that had been written by my father’s paternal uncle, and my father suggested that my mother play the heroine because they couldn’t find an actress who could sing,” says Mulgund. By this time, Joshi had been married to Sunanda Katti, but Vatsala went to Dharwad for rehearsal. The play was staged there as well as in Mumbai and Pune. Eventually, when she was 21 and him 29, they got married. Joshi’s first wife and children continued to live in Pune.

Vatsala passed away in 2005 and Joshi, who was also suffering from ill health, is said to have lost interest in life. “After that he sang only once, in 2007 at Sawai Gandharva festival and only because the year before he had promised the audience a performance. In 2008, when he got the Bharat Ratna, he missed our mother very much,” Mulgund says.

Over the years, concerts have become more common in the city throughout the year. Entertainment options such as television and OTT, combined with heavy traffic and parking problems, have made it difficult for people to go out and attend concerts. The pandemic too posed fresh challenges for artistes and organisers. The Sawai Gandharva festival, however, still keeps its flame alive. “It is not a profit-making venture as we do it as a service to our guru,” says Shrinivas.

At the Savitribai Phule Pune University, the Lalit Kala Kendra – which Joshi had actively set up – instituted a Bhimsen Joshi Chair in 1999 to mark the doyen’s 75th birthday. Through lectures, workshops, demonstrations and examinations, the Chair continues to raise new generations of artistes.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.