A language class is ongoing, but nothing about this class or the lessons are ordinary. It is a school for Santal children, where the medium of instruction is Santali—the only one of its kind in India. (Express)

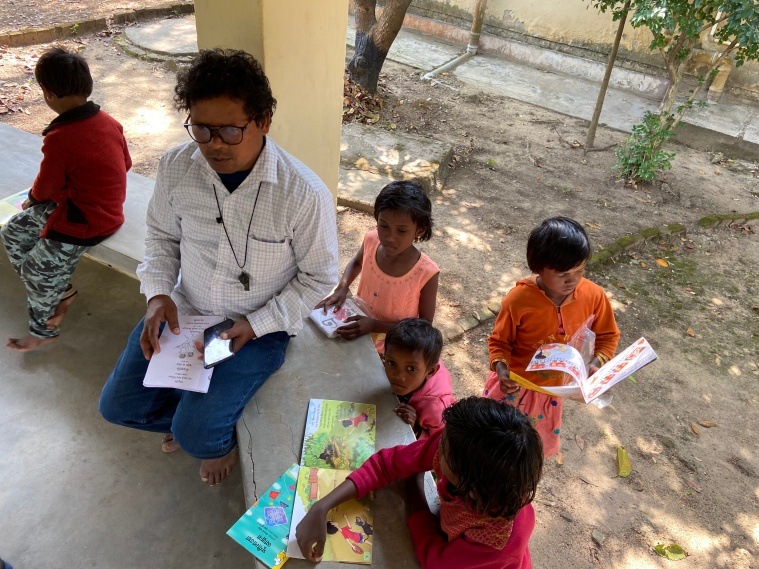

A language class is ongoing, but nothing about this class or the lessons are ordinary. It is a school for Santal children, where the medium of instruction is Santali—the only one of its kind in India. (Express) Dashrath Murmu is a patient teacher. Underneath a gazebo-like structure, some 20 children sit in front of a small backboard vertically propped up, and scribble alphabets into their books. Not everyone is paying attention, but Murmu gently coaxes and steers them back to the lesson, the last one of the day.

A language class is ongoing, but nothing about this class or the lessons are ordinary. It is a school for Santal children, where the medium of instruction is Santali—the only one of its kind in India. For three decades, Rolf Schoembs Vidyashram in West Bengal’s Birbhum district has been operating as a school entirely for Santal children, teaching primary school students.

Located approximately an hour away from Bolpur, more well-known in neighbouring villages by its abbreviation ‘RSV’, calls itself a non-formal school and is a privately run institution, which for many Santal children is their only chance at receiving an education and securing a better future. It was also why 26-year-old Kusum Baski made sure that her son was enrolled in the institution as soon as he was eligible. “If my children study in school, they will be educated. If they study, everything is possible. They will gain knowledge, they will be well, they can go anywhere. They will be able to make the right decisions on their own,” she says.

Linguistic barriers

In Asdullapur, a Santal village of fewer than 500 people, some three kilometres away from RSV, Baski has been toiling since morning in the paddy fields just beyond her home, with her infant daughter balanced on her back. As soon as her daughter is old enough Baski wants to send her to the same institution as her brother.

Located approximately an hour away from Bolpur, more well-known in neighbouring villages by its abbreviation ‘RSV’, calls itself a non-formal school and is a privately run institution, which for many Santal children is their only chance at receiving an education and securing a better future. (Express)

Located approximately an hour away from Bolpur, more well-known in neighbouring villages by its abbreviation ‘RSV’, calls itself a non-formal school and is a privately run institution, which for many Santal children is their only chance at receiving an education and securing a better future. (Express) A daily-wage labourer in paddy fields, Baski is well acquainted with the physical toll that the job has taken on her body over the years and she doesn’t want that for her children. “I have to work so hard under the open skies in the fields, under the sun. I hope that my children don’t have to work this hard. I’m sending him to school for that.”

Her seven-year-old son Suroj, is one of Murmu’s students and has big dreams, beyond his small village. “I don’t want to work in the fields,” he says. Suroj wants to be an educator just like Murmu.

For Santal parents like Baski, sending children to school can be hugely challenging, not because of the lack of access to government-run schools in the villages, but because of the language barrier that students from India’s tribal communities face. The medium of instruction in these government-run institutions is usually Bengali or English, languages that are foreign to Santal children.

Prof. Amit Kumar Kisku, the head of Vidyasagar University’s Anthropology department, remembers his childhood well and knows of the struggles that Santal students continue to face in India’s schools. “In my case, I studied in Bengali. I didn’t know what the teachers meant when they taught us about tota pakhi (parrot). I just memorised the words and later associated it with the bird and the word that we have for it in Santali,” says Prof. Kisku.

Language and knowledge are imparted through oral education, passed down from elders in the family and the community. The community has also preserved the Santali language this way. (Express)

Language and knowledge are imparted through oral education, passed down from elders in the family and the community. The community has also preserved the Santali language this way. (Express) Having observed the community from the proximity that he has, Prof. Kisku believes that the language barrier has been one of the primary reasons behind high rates of dropouts among Santal school children, particularly in West Bengal. Within the Santal community, education is imparted differently from what is witnessed in conventional classrooms.

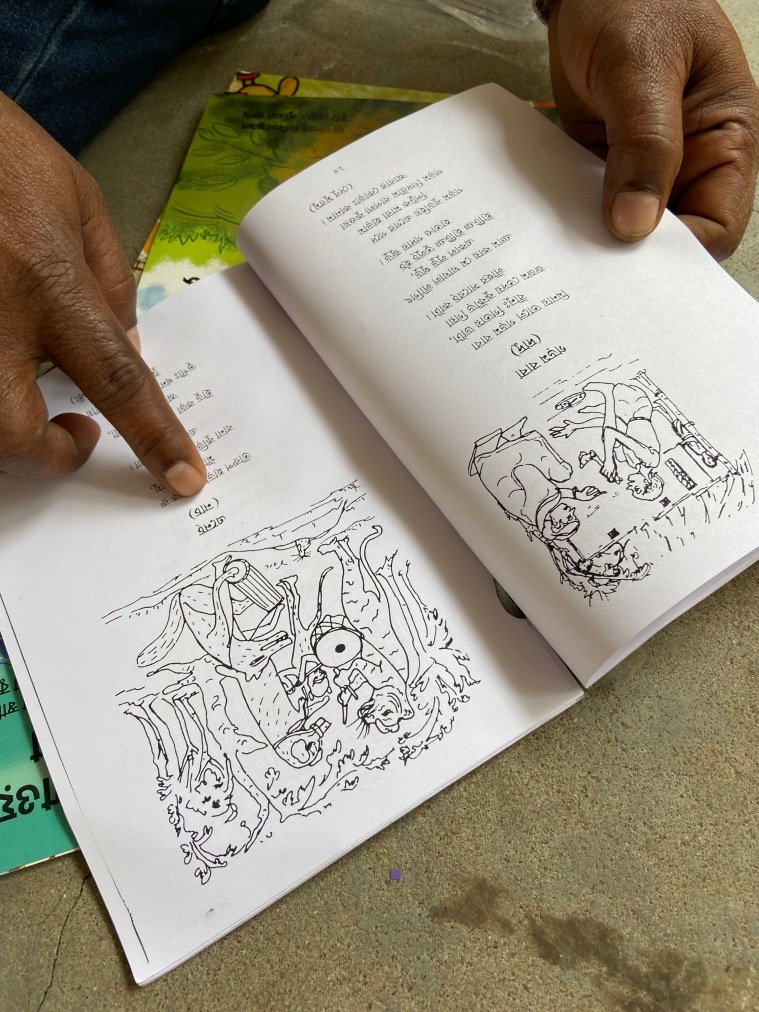

Language and knowledge are imparted through oral education, passed down from elders in the family and the community. The community has also preserved the Santali language this way. Earlier, the language did not have a particular script: for instance, Santals in West Bengal used the Bengali script, whereas those in Jharkhand and Bihar used the Devanagari script. But in 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santali to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, after which Ol Chiki has been recognised as a universal script for the language.

According to the 2011 Census of India, there are over 70 lakh (seven million) people who speak Santali across the country, and the community is the third-largest tribe in India, concentrated in seven states in large numbers, including in West Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand. The community’s geographic distribution is also spread across Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal.

“The financial conditions of most people in the Santal community are very poor. The children speak Santali at home, but go to Bengali-medium schools and have to learn Bangla. That becomes very difficult for them because they don’t understand what is being said in class and they don’t know how to communicate with the teacher,” says Sripati Tudu, an assistant professor in the Santali language at the Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University.

As a result, unable to cope, the students, particularly the very young, feel alienated in conventional classrooms and slowly lose the motivation to study, eventually dropping out of school. According to the 2011 Census, the literacy rate of the Santal community in West Bengal was 54.72 per cent, a figure that is lower than the national (73 per cent) and state average literacy rate (76.26 per cent).

This school tries to impart education in Santali by combining various aspects of Santal culture and life and conventional school lessons, that would help children transition to conventional classrooms after graduating from Class 5. (Express)

This school tries to impart education in Santali by combining various aspects of Santal culture and life and conventional school lessons, that would help children transition to conventional classrooms after graduating from Class 5. (Express) In West Bengal, there are several functioning government-run Santali medium schools in Bankura, Purulia, Medinipur, Jhargram, Birbhum, Hooghly, and Murshidabad districts, but these take in students from classes 1 to 12 and were established only in 2008, after repeated calls from the community. Educators in the Santal community say that the primary school years are the most crucial for students, when language skills are being developed, which is when most students drop out because of their inability to communicate confidently in languages other than Santali.

Language, identity and belonging

It was this gap that the founders of Rolf Schoembs Vidyashram wanted to fill when they first established the school in 1996, near the Ghoshaldanga village. The school is named after German astrophysicist Rolf Schoembs, who had given German educator Martin Kämpchen a considerable sum of money in his will for development aid.

Born in the Bishnubati village, Boro Baski was the first resident of his village to attend school and then go on to complete his master’s and doctoral degree in social work from the prestigious Visva-Bharati University in Shantiniketan, Bolpur. Now a social worker, Baski had understood early on that children in the Santal community needed an institution where they could learn in their own language and more importantly, feel that they belonged.

Baski, along with Kämpchen who was residing in Shantiniketan at that time, Sona Murmu, Gokul Hansda, and villagers from Ghosaldanga set up the Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha (GASS), under which RSV was set up as a non-formal institution for Santal children.

At RSV, the students have dispersed for lunch and Sanyasi Lohar, an administrator at the school, points to a large vegetable garden and fruit patch laid out beyond the open classrooms. (Express)

At RSV, the students have dispersed for lunch and Sanyasi Lohar, an administrator at the school, points to a large vegetable garden and fruit patch laid out beyond the open classrooms. (Express) This school tries to impart education in Santali by combining various aspects of Santal culture and life and conventional school lessons, that would help children transition to conventional classrooms after graduating from Class 5. Presently, 113 students come in from nine villages located within a three-kilometre radius to study at the school.

At RSV, the students have dispersed for lunch and Sanyasi Lohar, an administrator at the school, points to a large vegetable garden and fruit patch laid out beyond the open classrooms. “The teachers and students start their day by cleaning the campus and then we go to our open classrooms. The students also engage in organic farming, fishing, music and dance. We harvest the fruits and vegetables and give them to the students for their meals,” he says. The goal of these assignments is to study while holding on to their Santal culture and lifestyle where this knowledge is integral.

“We charge a nominal fee every month-Rs. 15. In the early days, it was Re. 1. We charge this money to make the child and the parents value the school. But if a family is genuinely unable to afford this, we do away with it entirely,” says Lohar. “There have been many cases like that in the past, but these days we see fewer.”

On one side of the large premises of the school is a hostel facility that provides boarding for girls and boys who require it. For many Santal families, the availability of a hostel attached to an educational institution can be a deciding factor in whether the child is able to pursue an education.

In the late 1970s, when the Left Front government came to power in West Bengal, it set up several hostels in what is known as the Jungle Mahal districts, where 90 per cent of the students living in the facilities were Santals. “I studied while living in a hostel and it is why I have managed to come this far in life. Had I stayed at home in the village, I may not have been able to,” says Tudu. These hostels provide Santal students with an environment conducive to learning that may not be available at home.

“In a Santal home, there will be domesticated animals to look after, household chores that the child is expected to do. Sometimes in a household if there is one child, the parent is compelled to take them to the fields because there isn’t anyone whom the child can be left with,” says Tudu. “When adults are away at their daily jobs, the child sometimes feels compelled to help with household chores even if the parent hasn’t asked for it, because of the environment that they grow up in, leaving no time for study.”

After-school hours

“Our teachers are also social workers. You need to understand the problems of the children. You can’t just say, ‘come to school’,” says Boro Baski. “If you go to the village or to their families, you will realise the kind of difficulties they face that stop them from going to school. Education is a luxury for them. Teachers sometimes have to go to the families to intervene in domestic problems.”

After the school day ends a little after noon, the students head back home, only to reconvene in the evenings for after-school lessons. (Express)

After the school day ends a little after noon, the students head back home, only to reconvene in the evenings for after-school lessons. (Express) RSV is not recognised by the government, Lohar says, but the Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha is, and the school is operated through this trust. “We didn’t try to get recognition because the government has several rules which we wouldn’t have been able to follow because of the way we impart education—differently from the conventional school. We wouldn’t have been able to follow those rules,” he explains. The school provides a certificate at the end of Class 5, which the students use to transfer to government schools. “The certificate has always been accepted and we have never heard of complaints.”

After the school day ends a little after noon, the students head back home, only to reconvene in the evenings for after-school lessons. Dusk is yet to fall in Bandhlodanga village, some 20 minutes away from RSV, and students trickle into Rina Hansda’s home for extra classes and help with homework. A large cotton mat is spread out on the ground outdoors and Hansda and her colleague, 28-year-old Gopal Marandi, sit with the 40-odd students who have come in.

Sometime in 2013, the Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha went to a handful of villages, from where the school received the highest number of students, to recruit teachers who would be available to help these students with after-school lessons. Hansda and Marandi, both residents of Bandhlodanga, had volunteered to help, and have been tutoring children from the village since.

For two hours every day, both gather on opposite ends of the village, with batches of some 20 students each, and try to give each child attention and help. “Their parents aren’t educated and those who have studied till Class 10, for instance, may not be able to give time to their children. The parents come home exhausted after a full day of physical labour and are too exhausted to help. The children don’t get guidance at home, and so these classes help them revise their lessons,” says Marandi.

Back in Asdullapur, propping her daughter on her hip, with a pail and trowel in the other hand, Baski heads home for the day. “I wanted to study but my parents weren’t able to educate me. We are poor people and I had many siblings. There was a paucity of food at home and school would have cost money,” she says. “I feel happy that my child is able to study. If he studies, he will be able to live well, he will be happy. That is what parents want.”

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.