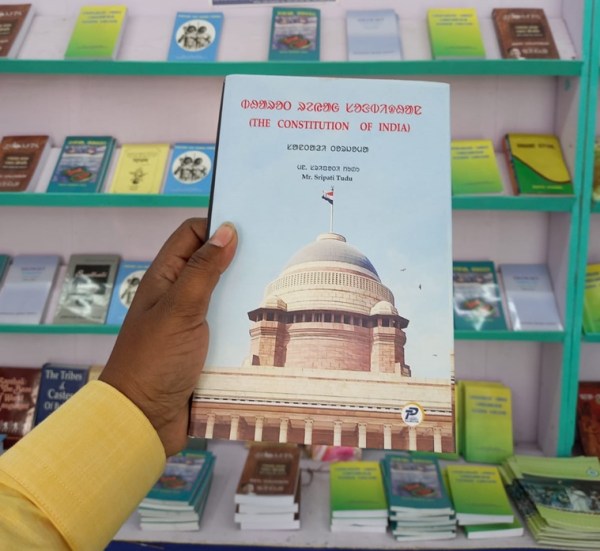

Translating the Constitution of India in Santhali had been on Professor Sripati Tudu’s mind for a few years (Express photo)

Translating the Constitution of India in Santhali had been on Professor Sripati Tudu’s mind for a few years (Express photo) Translating the Constitution of India in Santhali had been on Professor Sripati Tudu’s mind for a few years before he actually got down to starting the mammoth task: that of translating the longest written constitution of any country in the world—235 pages—in the Ol Chiki script.

An assistant professor in the Santhali language at the Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University in Purulia, West Bengal, Tudu started this initiative because he wanted the document to be more accessible and available for a wider group that may not necessarily be familiar with languages in which a translation of the Constitution is available. “The nation runs on the basis of the Constitution. But the community has been historically deprived and so people in the community need to read it to understand what their rights are, the provisions and what is written inside it,” Tudu told indianexpress.com.

In 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santhali to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, which lists the official languages of India, along with Bodo, Dogri and Maithili. This addition meant that the Indian government was obligated to undertake the development of the Santhali language and to allow students appearing for school-level examinations and entrance examinations for public service jobs to use the language.

According to the 2011 Census of India, there are over 70 lakh people who speak Santhali across the country, and the community is the third-largest tribe in India, concentrated in seven states in large numbers, including in West Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand. But their geographic distribution is not limited to India—the community is also spread across Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal.

In 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santhali to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, which lists the official languages of India, along with Bodo, Dogri and Maithili. (Express photo)

In 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santhali to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, which lists the official languages of India, along with Bodo, Dogri and Maithili. (Express photo) While the demands for the use of the language had been in the works for over a decade, the addition of Santhali to the Constitution’s Schedule VIII gave the language and the community an opportunity that had previously not been available. “At that time, the demand and scope for this language really increased. At the government level, it was taught in government schools. In West Bengal, we also got a Santhali academy,” said Tudu. In 2005, the Sahitya Akademi started handing out awards every year for outstanding literary works in Santhali literature, a move that helped preserve and give more visibility to the community’s literature.

For months before the chips fell into place, Tudu faced difficulties in finding a publisher for his book.“A large part of publishing Santhali books involves self-publishing, where the author has to put together funds. There are just five to six publications that publish Santhali books and they have a lot of conditions. They take a huge portion of the earnings, the copyright belongs to them etc.,” said Tudu.

Sometime in 2019 when Tudu met with Taurean Publications, a Kolkata-based publisher that had published its first Santhali language book only months prior, he found that it was eager and willing to publish his translation of the Constitution. “When the Covid-19 lockdown started (in March 2020), I began the work of translating it in earnest. I asked around, but the Constitution had never been translated in Santhali before. There were some who had translated parts of it, but it had never been done in its entirety this way,” Tudu said.

The book was published last year, and is available on Amazon and on the website of the publisher. Last week, at the Kolkata Book Fair, the Santhali version of the Constitution was also available for purchase at a stall run by the Paschim Banga Santali Academy.

Vinod Kumar Sandlesh, the joint director of the Central Translation Bureau, Department of Official Languages under the Union Ministry of Home Affairs, said “any Indian national can translate the Constitution in their own language”. The department oversees the implementation of the provisions of the Constitution relating to official languages and the provisions of the Official Languages Act, 1963. “They have every right to do so. They do not need permission for translations. The individual also has the right to generate income by selling their translation of the Constitution,” said Sandlesh.

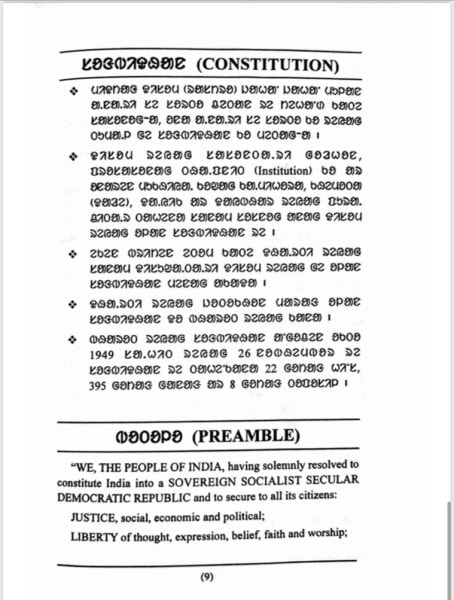

The first page of the Constitution (Express photo)

The first page of the Constitution (Express photo) Although finding publishers for Santhali language books is hugely difficult, in Tudu’s case, the challenges began only once he started the translation, because of the complexity of the terminology. The process involved multiple readings of the Constitution in English and Bengali to understand the nearest approximation of the terms in Santhali. “The words of the Preamble are so difficult to translate. So many terms didn’t have a Santhali word for them. I finished reading an entire Santhali dictionary but I couldn’t find the right terms,” Tudu recalled.

Tudu points to words like “dual citizenship” for which he struggled to find a Santhali equivalent; these eventually had to be explained in short phrases, with the original term in English typed next to it. “I couldn’t really ask others for help because there were very few people who had read the Constitution and were also fluent in Santhali. There are a few Santhali professors of political science whom I spoke with to understand concepts before translating, but there were times when they did not know the right Santhali term for a word. They were able to explain it to me in Bengali, but they did not know the specific term for it in Santhali,” said Tudu.

Two months ago, 27-year-old Balika Hembram, an MPhil student at Vidyasagar University in Midnapore, purchased a copy of the Constitution of India translated in Santhali. “There is a lot of demand for the Constitution in Santhali among students in the higher secondary level,” Hembram said. She hopes to teach political science in schools to Santhali students and the translation is indispensable for aspiring educators like her.

The Constitution of India has special provisions for the development of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and the translation has been useful in providing a deeper understanding of laws, powers and the community’s fundamental rights for readers like Hembram.

Adivasi scholars often point to Article 21 under Schedules V and VI of the Constitution that set out the rights of tribal peoples to development in ways that affirm their autonomy and dignity, and are considered by many to be the foundation of Adivasi rights.

For a community, the Constitution’s availability in Ol Chiki script is giving a chance to more people to read it for themselves.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.