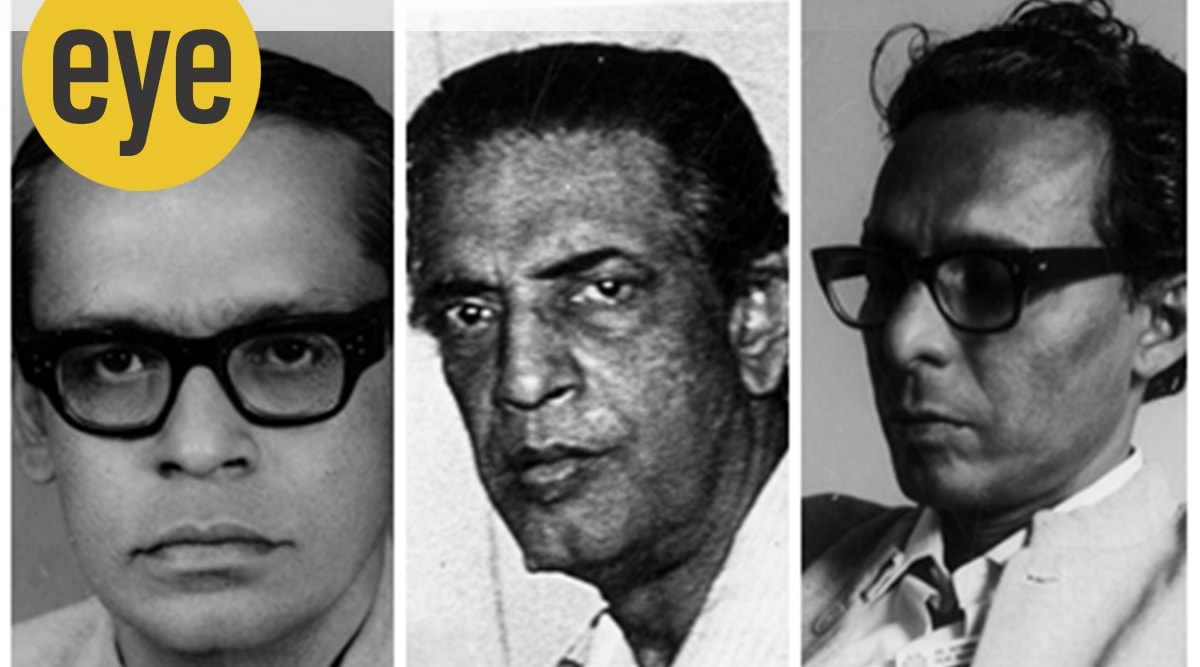

By revisiting the trilogies of the masters, Ritwik Ghatak, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Majumdar exhorts the pivotal role of Indian art cinema, as a tool of history, that looks at the past (India's march from an independent colony to a developing nation and the many could-have-been futures) to survive the present.

By revisiting the trilogies of the masters, Ritwik Ghatak, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Majumdar exhorts the pivotal role of Indian art cinema, as a tool of history, that looks at the past (India's march from an independent colony to a developing nation and the many could-have-been futures) to survive the present. A rock must land on our heads if one dismisses ‘Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures: Film and History in the Postcolony’ as yet another instance of a sentimental Bengali delving into that favourite Bengali pastime: discussing the past (an escape from the dystopian present — sociopolitical, cinematic) and the actors of history (not Tagore, Vivekananda or Netaji but the cinematic triumvirate), that enthuse as much as divide this ethnolinguistic group. Author Rochona Majumdar fills a gaping lacuna. While Bollywood/Hindi commercial films have been the poster child of popular and scholarly writing, Indian art cinema, like everything else to do with the form (state support, funding, exhibition), has often received the stepchild treatment.

Majumdar locates her oddly accessible academic book — exhaustively researched, evocative compendium of critical inquiries into Indian art cinema — in the “postcolony”, the post-independence decades, whence emerged directors such as Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray. Postcolonialism, to quote professor-writer Jane Hiddleston, unlike anti-colonialism, “which names specific movements of resistance to colonialism”, is “panoptic”, is the “multiple political, economic, cultural and philosophical” effects of and “responses to colonialism from its inauguration to the present day” — it is what Majumdar describes as the “long present”.

Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures: Film and History in the Postcolony; Rochona Majumdar; Columbia University Press; 307 pages; Rs 699 (Source: Amazon.in)

Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures: Film and History in the Postcolony; Rochona Majumdar; Columbia University Press; 307 pages; Rs 699 (Source: Amazon.in) Around their centenaries, the occurrence of a book like this one calls to attention the need to look back in anger, to the “forgotten futures”, the “utopian desire for unity” Ghatak ended his meditations on loss and longing with, the “betrayal of ancestors” that Sen invokes, to “hammer” in the speciousness of democracy — jolting public into “questioning national sovereignty, when people remained poverty-stricken, unemployed, insecure in the new republic of India”, for the “the history of India is a continuous history” of “exploitation, deprivation and poverty” while “thinking about cinema amid a maelstrom of leftist politics and violence”, to the faded optimism of Ray (in Mahanagar, “Arati voices her criticism of gender and racial discrimination pointing to a more equitable, yet unattained, future”).

Majumdar begins with the early efforts of English film-society activist-critic-filmmaker Marie Seton in the 1950s to establish “art cinema” as a universal idiom and the government’s Film Enquiry Committee of 1951 identifying art cinema as “good cinema” — aiding the nation-building process.

In beginning with Ghatak and ending with Ray, one hopes it is a righting of a historical wrong, an “epistemological break” from the time-worn engagement, popular and critical, with Ray, overshadowing his confrères. But, in the delineation of the postcolonial historical film, Ghatak is the most obvious point of entry.

What Majumdar does, to borrow from cultural theorist Roland Barthes, is consider the films, i.e. the texts, as the theory itself. She treads a fine line between interpretation and theorising. One has to agree with former New York Film festival director and writer Richard Roud, “the most rewarding way to study cinema is by considering films and filmmakers rather than the evolution of the medium”.

Majumdar problematises history through the trilogies of the respective auteur’s: Ghatak’s 1960s’ Partition trilogy (Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar, Subarnarekha), Sen’s (Interview, Calcutta 71, Padatik) and Ray’s (Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya) 1970s’ city films. If the “tragedy of Partition” was desolate and unrelenting Ghatak’s “lifelong obsession”, the Bengal famine (and, thus, food shortage) was angry Sen’s cinematic deliberation, the city is the film’s site for historical exploration for both Sen and Ray, but the “baffled” and “non-combative” Ray, who transitioned from a chronicler (a “Nehruvian template” as India transitioned from “a colony into a developing nation”) to an ethnographer, documented “the contemporary as deadlock in nation’s history”, the “script of historical transition” (from a now-free/postcolony to a developing nation) is “lost in his city films”.

Through framing shots and footage juxtapositions, Sen places Calcutta in a global setting (Vietnam and Biafra wars, etc. with the “long present” of the Bengal famine and Marxist/Maoist street-protests), while articulating the relationship between ordinariness and revolution. Sen created the original Angry Young Man on screen, much before Amitabh Bachchan’s rendition arrived in popular Hindi cinema to play the many Vijays, and yet, the political ambivalence, “complex and contradictory sentiments” of Sen’s Everyman disappeared from the Hindi film’s Angry Young Man. Missing, of course, is the woman’s question, especially displayed in the crisis of Ray’s historicism in his city films, women are ciphers, unlike their male counterpart’s “complexities/quirks”, theirs aren’t fleshed out. Ghatak’s woman was a sacrificial lamb, and Sen projected a disillusionment with the lack of intersectionality in the women’s movement, much like it was with the radicals’ fight in the name of the working-class peasants – both deflates.

History moves in circles. The first blow to art cinema, Majumdar notes, came with the restructuring of the National Film Development Corporation at the end of the 1980s (Indira Gandhi, through NFDC, gave “$6.5 million toward the $22 million required for Richard Attenborough’s biopic Gandhi”, which, among other changes like the boom of TV and video sectors, and move of social stories from film to television “contributed to art cinema’s continuing marginalisaton”), we are yet again at a juncture — a vortex — where the profit-oriented, loss-making NFDC is set for yet another restructuring, subsuming other, even bigger, public film bodies within its folds, and how the statist erasure of art cinema — and independent voices — might just be near-complete.

Majumdar “activates the pasts” to find in them “lessons” for “living in the present”. Art films, thus, offer “resources” with which to inhabit “our disorienting times” – “wracked by a global pandemic, authoritarian politics, [‘crises of refugees and migrants, of food and water, expanding precariat’], and tremendous might of neoliberal states challenging conditions of being citizens and humans”.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.