Students arrive at an elementary school for the first week of in-person classes after a week of classes were held remotely due to a high rate of Covid-19 cases,, in Atlanta, Jan. 10, 2022. (Dustin Chambers/The New York Times/File)

Students arrive at an elementary school for the first week of in-person classes after a week of classes were held remotely due to a high rate of Covid-19 cases,, in Atlanta, Jan. 10, 2022. (Dustin Chambers/The New York Times/File) Written by Julie Bosman and Mitch Smith

More than 2,600 Americans are dying from COVID-19 each day, an alarming rate that has climbed by 30% in the past two weeks. Across the United States, the coronavirus pandemic has now claimed more than 900,000 lives.

Yet another, simultaneous reality of the pandemic offers reason for hope. The number of new coronavirus infections is plummeting, falling by more than half since mid-January. Hospitalizations are also declining, a relief to stressed health care workers who have been treating desperately ill coronavirus patients for nearly two years.

All that has created a disorienting moment in the pandemic: Though deaths are still mounting, the threat from the virus is moving, for now, further into the background of daily life for many Americans.

Source: NYT

Source: NYT Patrick Tracy of Mundelein, Illinois, has seen the disconnect up close. In his county, new infections have fallen in recent weeks as the highly infectious omicron variant has begun to recede nationwide. But as those case rates were dropping, Tracy’s wife, Sheila, died from COVID. Sheila Tracy, 81, a native of Ireland who was devoted to her grandchildren and the roses she tended in her front yard, was vaccinated but also had underlying medical conditions.

“The people that don’t get vaccinated — you tell them that almost 900,000 have died, and they say, ‘They’d have died anyway,’ ” Tracy said. “We have very little consideration for our fellow man.”

The omicron surge has brought with it an especially potent and fast-moving wave of death across the United States. The country’s per capita death rate still exceeds those of other wealthy nations, a reflection of widespread resistance to vaccines and boosters in the United States. During the omicron surge, hospital admissions in the United States have been higher than in Western Europe.

The pace of deaths across the country has accelerated throughout the fall and winter. When the United States reached 800,000 deaths in mid-December, the most recent 100,000 deaths had occurred in less than 11 weeks. This time, the latest 100,000 deaths — many from the omicron variant — have been reported in just over seven weeks.

That the 900,000-death milestone comes more than a year after vaccines were first authorized added to the pain, said Dr. Letitia Dzirasa, the Baltimore health commissioner. Federal data shows that the vast majority of deaths have been unvaccinated people.

“As a public health professional, it is unbelievably sad, because I think so many of the deaths were likely preventable,” Dzirasa said. She said her agency continued to organize vaccination clinics each week but that some of them were “barely attended.”

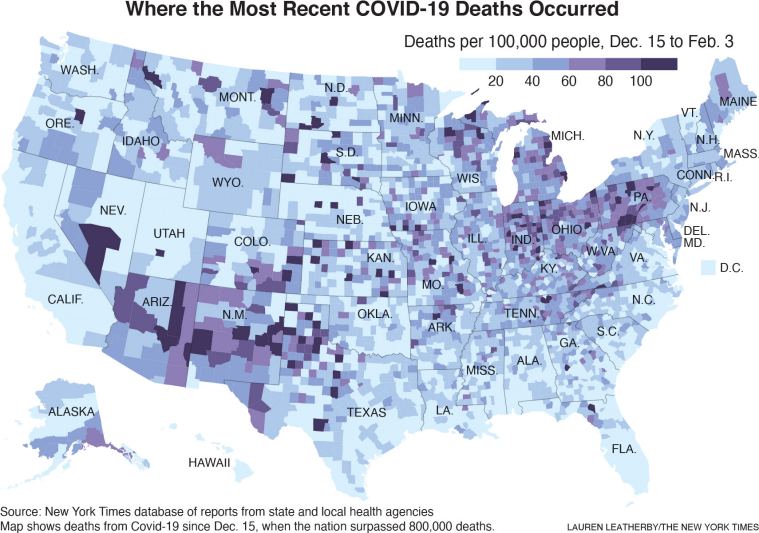

Deaths over the last seven weeks were reported in large numbers across the United States, with especially high rates in the Southwest and around the Great Lakes.

Much of the Midwest, Northeast and Southwest already were suffering large outbreaks fueled by the delta variant in December, before omicron became dominant. It is possible that many of the most recent deaths in those regions were caused by delta.

A month ago, when the omicron surge was driving cases to record highs, millions of Americans were out sick from work, coronavirus tests were hard to come by, and public health directors urged caution as hospitals filled. In the weeks since, as the outlook has improved, the sense of alarm has diminished.

In Cleveland and Detroit, where public schools briefly moved instruction online because of omicron, students returned to classrooms. In Chicago, city leaders said that they would consider lifting a rule requiring vaccination for indoor dining in the next few weeks.

The recalibrated message is more optimistic about the weeks ahead yet grounded in a more sober reality. The country is moving into a new phase of the pandemic, officials say, in which a virus threat will persist indefinitely but in which most people can rely on vaccines to protect them from the worst consequences.

“I’m going to go on a trip in March. I feel fairly comfortable reengaging in life,” said Linda Vail, health officer in Ingham County, Michigan, which includes the capital city of Lansing.

Vail said she remained worried about the dangers facing unvaccinated people, who continue to fill hospital wards and die. But for those who are vaccinated and boosted, and who do not have other conditions that make them especially vulnerable, she said it was important to accept some level of virus risk.

“It really is hard to get some people from that far end of being extremely fearful,” she said.

Kansas City Chiefs fans watch the 2022 NFL AFC Championship game at a pub in Kansas City, Mo., Jan. 30, 2022. (Chase Castor/The New York Times)

Kansas City Chiefs fans watch the 2022 NFL AFC Championship game at a pub in Kansas City, Mo., Jan. 30, 2022. (Chase Castor/The New York Times) The country continues to average more than 300,000 new coronavirus cases a day. That is down from more than 800,000 a day in the middle of January but still above the peak levels seen in every previous surge. More than 120,000 people with the virus are hospitalized nationwide, and deaths are being reported in higher numbers each day than at any point except for last winter.

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, increases in deaths have lagged behind spikes in infections because patients are often sick for weeks before dying and because it can take several days to report those deaths. The omicron variant, though still potentially deadly, tends to cause severe illness less often than previous forms of the virus. But because of the sheer number of cases — more than three times as many a day at the recent peak than in any previous surge — hospitalizations still rose to record levels.

Still, there is near-universal progress now, with case numbers plunging even in places like Montana and North Dakota that were among the last states to reach an omicron peak.

The improvement has been especially stark in eastern cities hit early by omicron. In the county that includes Cleveland, fewer than 300 cases are now being reported each day, on average, down from 3,200 a day around Christmas. New York City is averaging about 3,500 cases a day, down from 40,000 less than a month ago. The county that includes Chicago is averaging about 2,200 cases a day, down from 12,000 in mid-January, leading some to call for a return to fewer restrictions.

The virus has surprised scientists repeatedly, surging when experts thought it would ebb and mutating at speeds that initially caught researchers off guard. But there is wide agreement that COVID-19 will become an endemic disease, meaning that it circulates indefinitely at some level.

Some places are moving more quickly than others to treat COVID-19 like a routine fact of life. On Thursday, Gov. Kim Reynolds of Iowa announced that she would allow COVID-19 emergency declarations to expire later this month and that the state would scale back data reporting.

“The flu and other infectious illnesses are part of our everyday lives, and coronavirus can be managed similarly,” Reynolds, a Republican, said in a statement.

In the more than two years since the coronavirus was first detected in the United States, the country has sped past milestones that once seemed unthinkable: 1,000 dead, 100,000 dead, 500,000 dead. As the country reaches the latest marker, with 900,000 deaths linked to the virus — more than the population of San Francisco — the collective shock has lessened, even as the effect on victims’ families has grown.

“Everybody was so up in arms when we hit those first couple of milestones,” said Elle Stecher, a marketing manager in Lincoln, Nebraska, who recovered from a bout with COVID in January. But now, she said, “none of it is registering anymore.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.