Urf, new documentary on celebrity lookalikes in India, traces the individual artists' to find their primary identities

Geetika Narang Abbasi’s documentary Urf, currently playing at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, underlines that the work of a lookalike comes with an expiry date, that at some point, the need to find one’s own identity takes precedence.

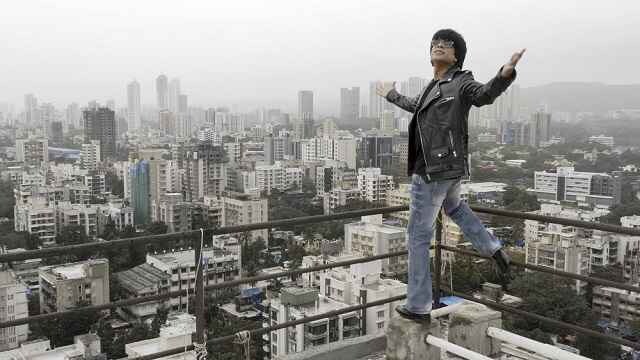

Still from Urf

He doesn’t imitate Amitabh Bachchan, he plays him. So insists Firoz Khan, also known as Junior Amitabh Bachchan, one of the three celebrity impersonators at the centre of Geetika Narang Abbasi’s documentary Urf [A.K.A], currently playing at the International Film Festival Rotterdam [IFFR].

Through a series of talking head interviews with Firoz, “Junior Dev Anand” Kishor Bhanusali and “Junior Shah Rukh Khan” Prashant Walde, the film offers us a glimpse into the world of what are known as “tribute artists,” lookalikes who play stars on stage, television, and in films. Interwoven with these interviews are vignettes from the production, promotion, and release of Amir Salman Shahrukh (2016), a minor movie starring lookalikes of three major Bollywood stars.

By means of relaxed exchanges in domestic settings, Urf examines the outlook of its subjects (and their family) towards their profession. Firoz “Bachchan” Khan emphasises that physical likeness to a star is only part of the requirement; the bulk of it, he says, involves research, practice, and hard work. Indeed, many of the artists we see in the film make up for what they lack in resemblance with a conscientiousness and charm that is impressive. Kishor believes that his mimicry of Dev Anand has a signature of its own that would inspire neophytes more than the star’s persona itself. Prashant is just happy if he could make people laugh, no matter in derision or delight.

Despite this touch of pride, their self-image proves rather conflicted. The three artists we see in the film are united in their desire to break away from being typecast and strike out on their own. All three appear to be on different stages of the same journey: Kishor, the most senior of the trio, has long transitioned into a busy career in light music. The middle-aged Firoz is now a regular on TV shows where he does not have to play Bachchan anymore. Prashant, for his part, seems at a crossroads, still trying to find his voice. The older men regard their earlier fascination with impersonation as youthful indiscretion.

In their testimony is a sense that the work of a lookalike comes with an expiry date, that at some point, the need to find one’s own identity takes precedence.

Underlying this ambivalence is a change in the nature of stardom and celebrity. In a mixture of wistfulness and self-deception, Kishor and Firoz view themselves as the last of their kind. The latter offers a striking diagnosis of why there are increasingly fewer impersonators in Mumbai: it is that there are scarcely any stars with their own styles anymore, absorbed as actors today are into an anonymous naturalist manner. And then, says Firoz, celebrity is not as scarce as it used to be. Technological advance, including multiplication of distribution channels, has meant that stars can be seen by fans any time they want, rendering the vicarious thrill of impersonators redundant.

Unusual though its subject is, Urf is a work that comes in the line of documentaries looking at various facets of the lives of impersonators. Premiering at the same IFFR 14 years ago, The Reinactors (2008) trained its attention on the community of lookalikes and cosplayers dotting the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Just About Famous (2015) normalised the practice, portraying these artists as consummate professionals serving a concrete cultural function. Perhaps the best of these documentaries, Bronx Obama (2014), spirals out from the private life of the president’s lookalike to explore America’s class and racial relations.

If celebrity impersonators in these earlier films were presented as social outcasts hustling to make ends meet, the individual we see in Urf can only be described as solidly middle class. We accompany Kishor on a visit to his spacious new apartment in a high rise, but professional doldrums aside, even Prashant seems financially better off than most of the hopefuls that make up the fringe of the Bombay film industry. At one level, their relative success marks them out as exceptions in a niche if competitive field, but it also reflects a vast demand for lookalikes that persists in spite of the pejorative associations the profession carries.

We see signs of this flourishing secondary market all through Abbasi’s film. The impersonators are featured performers in weddings and corporate events, play body doubles to their stars in commercials, and get top billing in parodies and B-grade knockoffs of popular movies. Urf relates this parallel economy to the insatiable thirst for celebrity that Bollywood inspires or, more often than not, manufactures. Ardent fans from all across the country assemble outside Shah Rukh Khan’s home to catch a glimpse of their idol, declaring with a zealot’s faith that “he will come.” Some of this adoration rubs off on his lookalike, Prashant, who is constantly asked for photographs by admirers who would not stand a chance of getting as close to the original.

These reflections notwithstanding, Abbasi’s film is a modest proposal. Unlike The Reinactors or Bronx Obama, it does not hazard wider socio-political arguments. There is certainly something to be said about the paradox that the work of these impersonators is devalued as being unoriginal by an industry that thrives on formulas and remakes.

But Urf is not the place for theoretical considerations. Abbasi’s film instead lets the human-interest stories take centre stage. It does not address the lookalike artists as a community. Its success, on the contrary, lies in individualising them, in letting them recount their journeys and aspirations without undercutting them. Far from the freaks of primetime television, they come across as decent, reasonable people providing for their families while trying to keep the inner flame alive.

Srikanth Srinivasan is a film critic and translator from Bengaluru. He tweets at @J_A_F_B.

also read

How extending my palette to beyond Bollywood helped me undo my stomach's inherent patriotism and vegetarianism

It took me years to realise I never took to meat because I barely saw it on the big screen. It wasn’t until I moved to Mumbai that I discovered a world outside Bollywood – and vengeful vegetarianism.

On Sidharth Malhotra's birthday, listing his six finest films from Ek Villain to Shershaah

The career-changing blockbuster, and one of Amazon Prime Video’s most successful indigenous products, Shershaah is to Malhotra’s career what Deewana was to Shah Rukh Khan and Jaanwar to Akshay Kumar.

Twitter Trouble? Siddharth could take lessons in apologising from Karan Johar, Kapil Sharma

What should Siddharth do if he doesn’t want to become the latest victim of cancel culture, where years of your life and career can be erased because of one offensive tweet/comment/act?