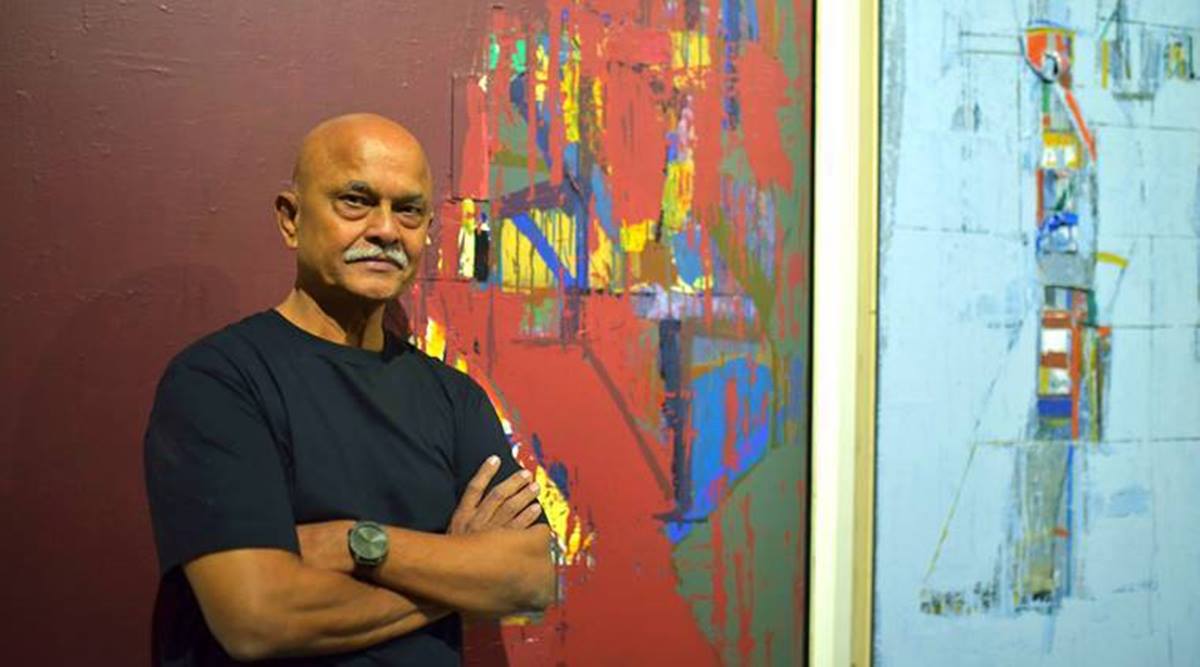

The lockdown has been Kolte’s most productive period, where he dared to have deeper conversations with himself, some of which resulted in bold installations. (PR handout)

The lockdown has been Kolte’s most productive period, where he dared to have deeper conversations with himself, some of which resulted in bold installations. (PR handout) He is not exactly a midnight’s child but he is 75 alright. And a polar opposite of what India has become. While the nation has aged with warts and speckles, well worn out with its cyclical routines of evolution, abstractionist artist and teacher extraordinaire Prabhakar Kolte feels just-born, frown lines hidden behind a child-like smile. Simply because he believes he has found his life’s purpose at 75, that of travelling within himself and exploring with the colours he has held within. If India became free 75 years ago, Kolte, who has been shaped by the nation’s history, has broken free now, giving free rein to his ideas to put together his most extensive collection ever with a bold passion play. He’s neither cynical nor transcendental, just plain elemental.

He isn’t exactly a rebel but won’t remain silent either. Returning to Delhi after 15 years recently, this time lending his name to the debutant Treasure Art Gallery (TAG), he says, “I never do subjects but situations and situations are such that I have to express them freely. The reality around me isn’t what it was. It has become melodramatic and vicious…the government is selfish and dead to me…so many people have died and are dying — and I am not talking about the pandemic — that we have become numb. Anything can happen to anybody and nobody will bother. Life is at its cheapest. I took this reality into consideration and started painting, delinking myself from the specifics of the externalities and expressing the honesty of felt emotions.”

“This is my way of living, my way to be heard,” he tells us, animating his beliefs with swinging hand gestures and luminous eyes.

Kolte, who began his early life with portraits, once painting 45 of them in 45 days, chose abstraction simply to have the freedom to choose his contexts.

Kolte, who began his early life with portraits, once painting 45 of them in 45 days, chose abstraction simply to have the freedom to choose his contexts. All the anxiety and angst that seem trapped behind the sombre monotones from his earlier work, tear through the canvas as streaks of bold, warm, colours finding their own way, a flesh and blood humanity breaking through the claustrophobic sameness and giganticism of superstructures or a superimposed authority, whichever way you might want to look at it. “When you get involved with your inner feelings, painting becomes a deeply intimate process,” says Kolte. There is a sense of materiality and texture that overlays each painting, a welling up of the truth that is desperately finding the light of day, a layering so complex that was never there in his earlier works. He deconstructs the geometric precision of black and white dots, splashing water on it when wet, the grey trickle a distillate of how fact and fiction lose their separateness. “Painting is a happening in itself and totally reflective of my mood, so there is tension and conflict in the here and now…I don’t see the past or the future, I just live in the present.”

So though Kolte has seen an India in change, that is not the subject of his paintings. But since they come alive in the moment of creation, they are palpable with the rawness of emotions and the human manifestation of that change.

Prabhakar Kolte, Acrylic on Canvas, 60-70 Inches, 2020 (Source: PR handout)

Prabhakar Kolte, Acrylic on Canvas, 60-70 Inches, 2020 (Source: PR handout) The lockdown has been Kolte’s most productive period, where he dared to have deeper conversations with himself, some of which resulted in bold installations. There’s a toy-like simplicity about broken bathroom fixtures, pieces of sanitaryware, broken taps, valves, used shampoo bottles and toothpaste, all of which have been painted over by white. “This way I removed the reality of their uselessness,” he tells us but what he really means is the way we whitewash what we have lost use for. The tyranny of a trapped childhood is represented through playful Lego cubes stashed behind a wire mesh. “Artist Paresh Maity and I were working in a space where these blocks were just lying around. And I could find a story in them.” Or take the slanted black frame of an upturned life with barred windows behind which are miniatures of Kolte’s own abstractionist art, colour pencils and daubs of spice-hot colours, again a symbolism of everyday life that refuses to give up despite being locked out.

Kolte, who began his early life with portraits, once painting 45 of them in 45 days, chose abstraction simply to have the freedom to choose his contexts. And he had inspirations and fearless idols to follow. “It has been a constant journey from the JJ School of Arts in 1962 and I am still travelling with no destination in sight yet. But I have been lucky to have had many milestones, having had a chance to interact with progressive art icons like VS Gaitonde, my teacher Shankar Palsikar, MF Husain, Hari Ambadas Gade… they weren’t bothered about living in the past or the future but reacted to the present. That, too, on their terms. The formlessness was incidental to their ideas that were flowing continuously and were evidenced by the play of colours. They were reactive and creative. That’s what inspired me to interpret the present. Having spent time with these modernists, I know I am not selfish but I have to live for my ideas, and frankly and truthfully react to the moment,” he says.

That’s how he shaped his artistic language and legacy, not painting a subject but becoming a subject for others to talk about. And he began breaking down the elitist barriers of art even as a student, defying formula at the risk of his grades. Recalling those days, he tells us, “If you want to do good art, you should be honest inside and outside. Figurative work was compulsory in our final year but by that time I came under the influence of Progressives and had started doing abstractions, without knowing much about the genre. My friends pleaded with me to complete my figures or I wouldn’t pass. I didn’t subscribe to the formula and I just scraped through. Those days art was a much freer space and about convergences. I interacted with a lot of poets and intellectuals in Marathi and these informed my work.”

Prabhakar Kolte, Acrylic on Canvas, 60-72 Inches, 2020 (Source: PR handout)

Prabhakar Kolte, Acrylic on Canvas, 60-72 Inches, 2020 (Source: PR handout) Ever since, he has stayed true to his spirit and followed his personal playbook, which some have found to be radical or simply outlandish. He has also been a teacher and served several committees on art promotion but has risked being labelled a “mad man” for suggesting freeing up the arts space, beginning with schools and institutions. “Art cannot be taught, it is about learning, not teaching. Students should be allowed to develop their own language of expression and teachers can guide them with their knowledge base. The degree matters little as the first class first student is nowhere unless he has become a teacher in some art school. The title of my idea is ‘teaching without teaching’,” adds Kolte who is pushing an arts residency project with Maity near Surat, where students can live for a month to pursue their passion unhindered with guidance and free boarding, equipment and facilities. The idea is to let them enroll in batches of 10, paint freely and engage in open dialogues and discussions.

It is his give-back moment frustrated as he is by the establishment’s encroachment of institutional spaces. “Our artists are neither united, nor is there anybody supporting them. And institutions like the Lalit Kala Akademi are now toothless. Earlier, they used to run camps and activities continuously. Perhaps they do not want to create good painters, they have enough budget but they don’t want to push change. The committees are just about signing files but nothing concrete happens, so I left,” the helplessness of driving change despite being one of India’s leading abstractionists evident in the raspiness of his voice.

And he’s exasperated by the silent censorship in the culture space. “Who can define vulgarity and morality? Who can define these, these are very personal, nobody has a copyright on these as a free man of this country. Fanatics destroy nudes because they are illiterate. Politicians are not interested in the arts. Students are more bothered about survival and creativity is secondary. It should be the other way around. If they do that, we won’t need politicians to survive.”

Prabhakar Kolte, Acrylic on Canvas, 60-84 Inches, 2020 (Source: PR handout)

Prabhakar Kolte, Acrylic on Canvas, 60-84 Inches, 2020 (Source: PR handout) In fact, it is to democratise the art space that Kolte is dedicating the next two years of his life to curating young artists. He feels that art would cease to exist if the young continue to be motivated by the business rather than being honest about their expression. “In the UK, I saw an art school where each student had a 8×10 ft studio. Students bring their stuff, remain for 10 hours and stay with their creation. JJ is existing but nothing is really happening. We put 70 students in one big hall and they end up chatting than finding their spaces and identity,” says the maestro, who himself might go full circle, trying a hand at portraits with the honesty of his grammar that he has developed over the years. As if as a reminder, he has mounted some of his early portraits — a captain of a ship, his son and his wife’s friend. For Kolte at 75, these have vanished from his mind and it is the instantness of an unfolding moment in time that is, in his words, “charging me up.” The next daub of colour will tell a new story.

📣 For more lifestyle news, follow us on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook and don’t miss out on the latest updates!

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.