January 16, 2022 3:30:47 am

Fatima, Savitribai, and what they stood for and against

Fatima, Savitribai, and what they stood for and against (Written by Rosalind O’Hanlon)

The month of January is a particularly special time in the long history of popular struggle for education in India. On January 3, we celebrate the birth anniversary of Savitribai Phule, the lion-hearted pioneer of education for women and the socially marginalised, whose name now graces one of Maharashtra’s premier universities, Savitribai Phule University in Pune. On January 9, we salute what tradition marks as the birth anniversary of Savitribai’s fellow pioneer teacher in Pune, Fatima Sheikh.

Much of their history — particularly that of Savitribai — is now familiar to us. But it is still difficult to think of this pair without a thrill of wonder at their courage and breadth of vision. For, when the power of colonial rule was at its mid-19th century height, and the hold of conservative attitudes amongst many communities was yet to be seriously challenged, these two women stood forth to argue the case for education as a right that all should enjoy, not only the privileged few. And they did so not in one of the great cosmopolitan centres of colonial India, but in the city of Pune, the old headquarters of the 18th century regime of Maharashtra’s Brahman Peshwa rulers, and still in the mid-19th century, very much a bastion of social conservatism.

Many elements of their stories are now well known to historians. As the wife of Jotirao Phule, the great social reformer and campaigner against casteism, the young Savitribai joined her husband in establishing schools in Pune for girls, Dalits and other disadvantaged communities. Jotirao’s friend, Mian Usman Sheikh, a fellow resident in the city’s busy trading quarter of Ganjpeth, made space in his own home for the first such school, established in 1848. Savitribai and Usman Sheikh’s sister, Fatima, took on the work of teaching a small group of girls there, with the help of an American missionary based in Ahmednagar.

Other schools for Dalit and Bahujan children followed. The two women worked tirelessly, not only in the classroom, but going house to house in the city to promote the work of their schools, and to persuade reluctant families that they might safely send their children there. Such a stunning challenge to the conservative social norms of the city naturally drew opposition. The women faced a barrage of stones, mud and name-calling as they went about their work. Faced with such public disapproval, Phule’s father felt he had to ask the couple to leave the family home. Once again, Usman Sheikh came to their rescue. He offered them a place to stay in his own house, where the pair lived until 1856, when a temporary illness forced Savitribai to return to her own family home in Naygaon near Satara.

Owing to the labour of many researchers in the field, we know much about Savitribai’s subsequent life and career. But Fatima Sheikh remains a much more elusive figure. She did not leave any writings that have survived, and as a Muslim woman, she did not benefit from the energy of generations of Dalit and Bahujan scholars seeking to preserve her memory. Her name is now rightly celebrated, and a brief mention of her life features in Maharashtra’s Urdu school textbook, and in the textbooks of Bal Bharati. But much of the direct evidence of her life has been lost.

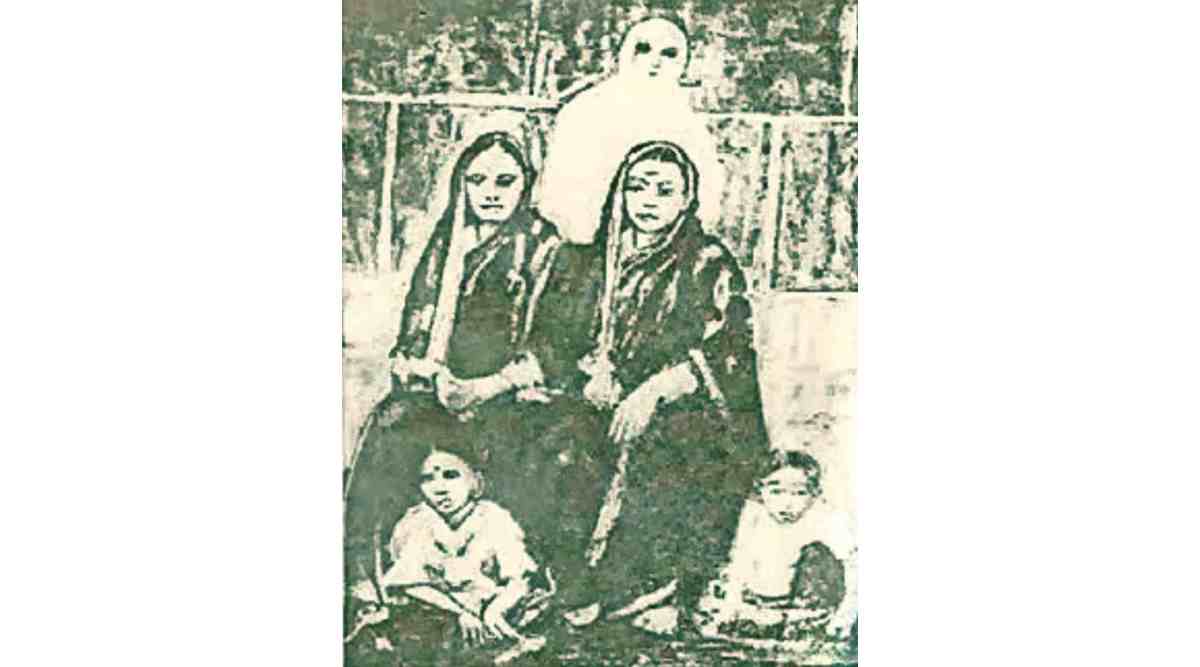

Fortunately, though, we do have a contemporary photograph of her, reproduced in this column. Although it is widely available on the Internet, most images that circulate of Fatima — and indeed of Savitribai herself — are modern artists’ impressions. But the photograph does deserve closer examination, and in fact can tell us quite a lot about Fatima, her circumstances and her role as a teacher. We can date it to the 1850s, when the technology of the daguerreotype was just beginning to make photography more widely available in India. We know that Phule himself and his progressive co-workers were familiar with the possibilities of early photography, since early images of a young Jotirao still survive.

The photograph here shows Savitribai and Fatima sitting side by side. Savitribai looks directly into the camera, while Fatima — possibly a little less comfortable with the technology — is looking away. The two women are dressed in strikingly similar saris, plain in colour, with simple and strong borders. This suggests that they wished to present themselves as professional teachers, clad in the same simple but dignified uniform. Their saris are tied in the ‘modern’ nivi style, popularised during the colonial era as women ventured more into public life and required a modest style of sari drape to cover arms and legs. Their pose is very much that of professional partners and co-workers, accustomed to working as a team and with a quiet poise in their presence.

Standing behind them is another very interesting presence, giving us further clues to the life of the household. Watching the two women, but also herself gazing directly into the camera is what looks like an older female figure. She is dressed in a traditional white khimar hijab, designed to cover the upper body of a Muslim woman. It may be that this photograph was taken during the Phule family’s stay in the house of Sheikh, and that the older woman was a senior family member — but one who nonetheless also wished to appear as a member of this group of early professional educators.

Perhaps — and here one speculates — she may have been another member of the Usman household, who helped make it a welcoming refuge for Savitribai and her husband. Two little girls sit at the two women’s feet. From the marking on her forehead, the child on the left seems to be from a Hindu background. The little girl to the right, on the other hand, looks to be wearing a child’s version of the khimar hijab. These two children clearly echo the main message of the photograph, of solidarity in the cause of women’s education that reached across the boundaries of age, social background and religion.

The photograph brings us just a little closer to Fatima, and her friendship with Savitribai. We salute both.

The writer is Professor, Indian History and Culture, University of Oxford

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.