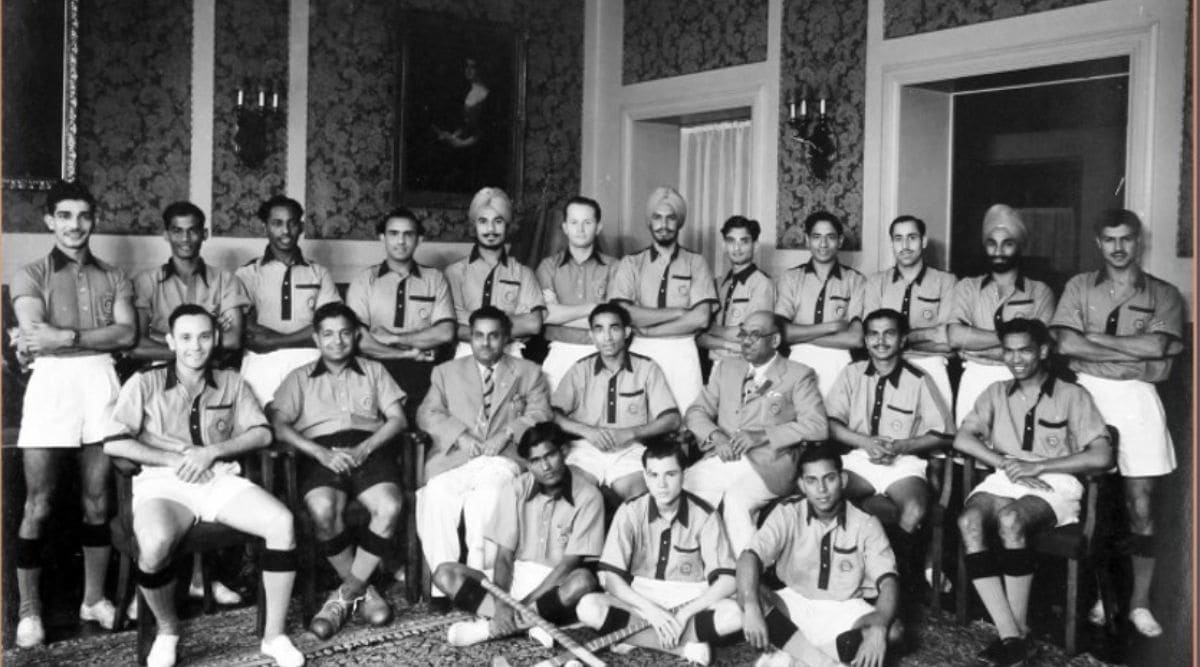

The Indian hockey team for the 1948 London Olympics. Grahnandan Singh (Nandy) and Keshav Datt (standing 2nd from right and right). (Pic credit: Taangh.com)

The Indian hockey team for the 1948 London Olympics. Grahnandan Singh (Nandy) and Keshav Datt (standing 2nd from right and right). (Pic credit: Taangh.com) Lahore’s Government College had five hockey players at the 1948 London Olympics — two from the newly-born Pakistan, three representing freshly-partitioned India. Classmates till a few months ago; they had parted with heavy hearts and scars that would never heal.

Among the countless casualties of 1947’s sudden geographical demarcation was the brotherhood of the Lahore-dominated combined Punjab team, the national hockey champions of undivided India. The new markings on the old map had split the close-knit hockey team along communal lines. Post partition, almost overnight, the solidly fortified 5-3-2 had holes at the positions occupied by the Hindus and Sikhs. They would get scattered, get busy with their lives, grow old, and eventually lose touch with their Muslim friends.

Till Bani, the 59-year-old daughter of double Olympic gold medallist Nandy Singh, thought of capturing on camera the heart-warming tale of the friendships firmed up on sporting fields that had survived turbulent times and the widening wedge between two bitter nations.

Titled Taangh — longing in Punjabi, the documentary has been premiered at the ongoing Trivandrum film festival and has black and white clips of young men in flappy loose shorts snaking through defenders, giving an early warning to the world about the subcontinent’s intention of owning field hockey at Olympics.

The priceless archival footage is artfully embedded in between interviews of those mesmerising stick wizards, now frail and weak, some in wheelchairs, shedding tears while talking about the days of winning medals, and losing friends.

The documentary began to take shape in November 2013, and Bani went to Lahore in Febuary of 2014. Her father would pass away the sane year. “I took up editing 2 years after that and it finished this September,” she says.

Bani with her father Grahnandan Singh (Nandy) (File)

Bani with her father Grahnandan Singh (Nandy) (File) Recording father’s legacy

What had started as a daughter’s amateurish effort to save her two-times Olympic gold medal winner father’s hockey stories for posterity would turn into an ambitious project.

“I missed out on knowing my father as a champion. By the time I grew up, his playing days were over. I guess my parents’ memories are important as they underpin mine. Every time I asked him about his hockey days, he would say go meet my buddies,” she says. After a brain stroke, Nandy Singh lost his speech and was partially paralysed but Bani’s drive would be undeterred. She would reach out to her father’s buddies.

The documentary sees her traveling to Kolkata to meet her father’s mate from college days in Lahore, Keshav Datt. He played centre-half for the Indian team that beat England at London in 1948 to win gold and, as the narration informs, made the future Queen of Britain stand up to Independent India’s national anthem.

It was during one such interaction that Datt would share a nugget from his final days in Lahore that would make Bani restless to cross the border.

The journey to her roots, searching threads that connect to her father’s youth, dominates the second half of this lovingly put-together tribute to India’s first sporting heroes. It’s the mutual longing of the two Punjabs, on either side of the border, to scale over the fence and revisit the land of their forefathers that gives the documentary its name.

But, in case, Bani hadn’t opted for Taangh, a title with gravitas, she could have well settled for “Searching for Shahrukh in Lahore”. It would have been apt. Shahrukh who?

The story goes that Keshav was part of the combined Punjab team that had traveled for the Nationals. That was early 1947, Lahore was burning. Keshav’s family couldn’t take it anymore. They would join the mass migration headed to Delhi. The plan was that Keshav wouldn’t return to Lahore after the Nationals. “They told me to get off at a few stations before Lahore and join the family in India. But with several Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus in the team, I thought I would come across as a coward to part ways with the team before Lahore,” he says.

But on reaching his empty home, Keshav would feel like an unwanted outsider in his own Lahore. He feared the armed mobs that hit the streets at night looking for Hindus and Sikhs. Enter Shahzada Shahrukh, his close friend from college and Punjab teammate. The trusted defender with rakish good looks would quell Keshav’s frayed nerves, and lull him to sleep.

In a chilling account, Keshav relives the trauma. He narrates how the very next morning Shahrukh would smuggle him to the railway station in a car, get him tickets and even put in a word for his friend’s safe journey.

Those were times of uncomfortable goodbyes and horror tales of trains with bloody stains. The childhood buddies would curse fate and circumstances that were thrust on them.

Making it to two Olympic teams

In a fresh twist, both would make it to their national teams for the Olympics. Pakistan’s vice-captain was Shahrukh and India’s trusted centre-half Keshav. While parting at the Lahore railway station, the London reunion within months was beyond their wildest dreams. Far away from their home, in London, they would catch up for coffee, talk for hours about their college days and the hockey games they played for Punjab.

But this wasn’t their good old Government College campus. Times had changed, there was an air of mistrust among old neighbours. The managers of both teams would ask the two friends to keep a distance. They did and with time they would grow further apart.

It was close to seven decades later, Bani made it her mission to locate her father’s and Keshav uncle’s dear friend in Lahore. The pursuit wasn’t easy. A Pakistan visa was difficult to get and Shahrukh was untraceable. Among the many setbacks she talks about in the documentary, there’s one about a gut-wrenching message Bani got from her contact in Pakistan. Shahrukh had died, an email informed her one morning. She was shattered, she thought her labour of love had been binned. Without Shahrukh the story was incomplete.

To her relief, it was proved to be fake news. “Later, I got a mail saying he was surely in Lahore but there was no address,” says Bani.

After several attempts, Bani would get the Pakistan visa. She would fly over the border that her father was forced to cross with mere memories of their lost home. Her original ancestral home, the land of her forefathers would welcome her with love. Lahore Government College would honour her. They were not aware that three of their own, now in India, had won two Olympic gold. They would sent mementos for her father. Bani would be a chief guest for an impromptu hockey game. She would also get Shahrukh’s address.

The moment of the documentary is when Shahrukh is wheeled into his home’s living room to meet the unexpected guest from India. Bani introduces herself and hands over framed pictures of her father and Keshav to the charming handsome man in a wheelchair. Shahrukh checks if he could keep the frames. Bani nods a yes. The old man plants endless kisses on the pictures of his old mates.

Bani had plans to connect the three on a video call, none agree. “They said our memories were better,” she says. Shahrukh tells Bani not to tell her father that he was wheelchair-bound. “Meri haalat dekh ke tera Abbu roeaga,” he says. He knew his friends well. The final frame of the documentary has Bani’s Abbu with tears in his eyes as he watches the pictures of his old friend from Lahore.

The documentary was also a sort of piecing together, a search of her roots and the story of her family’s origins. “I have been trying but am unable to pen down something about the ‘watan‘ my family lost. It is this gap in their stories that pulled me to Lahore. I wanted to understand what made them who they were and the answers lay in the land they came from.

“The irony is that their watan cannot be documented in the history books,” she says. “The watan is not a land that can be captured within political borders. It lives on in memories and stories that our parents tell us and this film is my way of passing on their stories to the next generation.”

In the seven years it took to make the documentary, all three friends passed away. But the story of Nandy and his buddies Keshav and Shahrukh lives on, reminding the world about the sturdiness of the seemingly fragile Indo-Pak hyphen that refuses to snap despite wars and failed dialogues.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.

Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google

Continue with Google