From Olympic glory to fleeing prostitution, these youths were realising their dreams. Now all hope may be lost

They were poor but on track to beat the odds. Then the COVID-19 pandemic struck. The programme Insight meets young Indians whose once-promising futures, like graduating from a top university, are slipping out of reach.

Sunil Chauhan was training to be a top boxer; Avnish Kumar made it to Delhi University but had to drop out; Tabassum Jahan's family does not have enough to eat.

NEW DELHI: Brothers Sunil and Neeraj Chauhan were on their way to sporting glory — boxing for Sunil, 23, and archery for Neeraj, 19. It was what their father, Akshaylal Chauhan, had worked so hard for.

As a cook in a stadium in Meerut, India’s “sports city” in its most populous state of Uttar Pradesh, Akshaylal earned 12,000 rupees (S$220) a month.

The 51-year-old’s income from cooking for sportsmen and officials was barely enough to support his wife and three sons. So on most nights, he cooked at weddings and parties to earn extra. He worked up to 20 hours a day to help Sunil and Neeraj train and excel in sport.

The brothers progressed steadily over the years, winning medals at the junior, state and national levels. Neeraj, for instance, won silver in the 50-metre event in the Senior Archery Championship 2018. Sunil, meanwhile, won gold early last year at the Khelo India University Games, a national multi-sport event.

Then COVID-19 struck, and their father lost his job when the stadium canteen closed during the lockdown.

“First, the lockdown was for 12 days. We thought we’d manage somehow,” he told the programme Insight.

But the pandemic was only starting to play out. The family soon became desperate, and the brothers needed to keep up with practice. Akshaylal started a vegetable stall but struggled to provide two meals a day for the family.

Sunil and Neeraj had to stop training and help their father out.

A lifeline came in October last year when the then sports minister, Kiren Rijiju, announced that owing to their “acute financial crisis”, the brothers would receive 500,000 rupees each under the Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay National Welfare Fund for Sportspersons.

This is where the brothers’ stories diverge.

Neeraj, who completed Class 12 or the equivalent of A levels, has since found a job with the Indian paramilitary force known as the Indo-Tibetan Border Police. This month, he was declared the best male archer at the All India Police Archery Championship — part of the All India Police Games, the first to be held post-COVID.

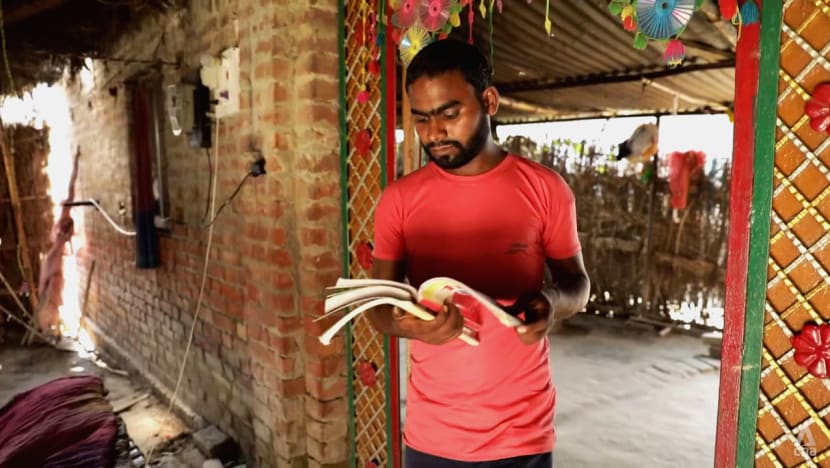

Sunil, on the other hand, has not found a job that will allow him to continue training. He said the government grant the brothers had received last year was spent on sports equipment and family expenses following the lockdown. His dream of competing in the Olympics is almost over, he said.

“To be an international boxer, one needs to strictly follow a proper diet, training and rest protocols … designed by a personal coach. Boxing is a difficult sport where injuries to the knee and shoulder are common, and the reason is not following a proper diet.

“Without training, how can I perform in any tournament?” said the first-year college student, who is pursuing an arts degree and used to train for 10 hours a day. “Everything is finished.”

Tenacity is what some Indian youths have in spades, but that may not be enough in the face of the pandemic. And sporting dreams are not all that have been snuffed out.

A STARK CHOICE: FAMILY OR EDUCATION

Elsewhere in Uttar Pradesh, 20-year-old Avnish Kumar seemed to have beaten the odds in his village of Narayanpur when he aced his Class 12 exams and was admitted to the prestigious Delhi University to pursue an honours degree in history.

If I focus on my education, then my family will become unstable. If I leave my family for my education, then the family will be destroyed.

His achievement was remarkable, given that the literacy rate in his village is only about 60 per cent. But COVID-19 forced him to choose between family and getting an education to fulfil his ambition to become a civil servant.

After his father caught the coronavirus and died in June, he dropped out of college and returned home. He set up a shack to sell some items to earn a few rupees. He has also put his academic skills to good use, teaching village children in the afternoons.

He wants his six young brothers and sisters to continue in school, but they need money to pay their fees. Since the pandemic, one of his brothers has already left school to look for a job, and a sister has also dropped out.

“If I focus on my education, then my family will become unstable. If I leave my family for my education, then the family will be destroyed,” he said.

“When I took admission to Delhi University, I had just one aim: To crack the UPSC (Union Public Service Commission) examinations. I wanted to give my 100 per cent … But first, Father’s health deteriorated. Then the pandemic came, and my education was interrupted. Now I think it’s interrupted forever.”

COVID-19 has killed over 464,000 people in India, and its second wave from April to June left more orphans in its wake than the first, child rights activists have noted.

Since then, India has had relative success in vaccinating its population of nearly 1.4 billion. It has administered over 1.14 billion doses, and 28 per cent of its population has been fully vaccinated, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

But according to anti-poverty charity Oxfam India’s chief executive Amitabh Behar, “beyond the vaccines, we’ve really not been able to handle the situation well”.

“Apart from the vaccination, we’ve really fumbled all around,” he said.

Observers also note that lockdowns and prolonged school closures have caused children to lose what they have learnt before. “It’s not just that they’ve lost these one or two years, but that they’ve gone back further,” said Amit Basole, an associate professor of economics at Azim Premji University.

“Children who were, let’s say, in grade three or four at the beginning of the pandemic should now be in grade five or six. But in learning terms, they may actually be back to level two.”

This, said Behar, is a “massive crisis”. Many have likened the pandemic to an X-ray that has highlighted the country’s cleavages, inequality and poor health infrastructure, he added.

WATCH: What COVID-19 Has Cost India's Youth: Of Lost Hopes & Broken Dreams (47:38)

ESCAPING SEX WORK, BUT IN LIMBO

Among the vulnerable members of Indian society is 19-year-old Rani (not her real name), born into a community where girls are forced into prostitution when they are in their early teens. Her mother and a sister are sex workers, but Rani resisted and ran away to Delhi with her younger sister.

The two girls managed to get into a school, and Rani, whose name has been withheld to protect her identity, performed well in her senior secondary school leaving exams. Then the hostel where she and her sister lived closed owing to the pandemic, and they had to return to their hometown.

They discovered that their mother had “sold everything”.

“She said, ‘You don’t need to contact me again. To me, you all are dead,’” Rani recounted.

With their studies disrupted, the sisters are being put up by friends and civil society activists in Delhi and managing to avoid the path taken by their mother — for now.

“We thought that after completing our education, we’d do something and secure our future,” Rani said. “Everything was so useless after lockdown. There was no motive in life. What to do? We were totally blank.”

Behar said he hears these “heart-wrenching stories” from his Oxfam India colleagues “pretty much on a daily basis”.

Sex predators also turn up at red-light districts to tell mothers to give up their children in exchange for food, said Ruchira Gupta, founding president of Apne Aap Women Worldwide, an organisation working to end sex trafficking.

“They’d sometimes say, ‘We don’t want physical sex, but we want to use them to make porn videos, and it’s not going to harm the child … Why don’t you let us have your daughter? She’s doing nothing at home,’” said Gupta, who is also a professor at New York University.

The Indian government has announced socio-economic measures for youths, such as the PM CARES for Children scheme, which supports the education of children who have lost both parents or their surviving parent or legal guardian to COVID-19.

“We’re absolutely confident that the younger generation will be put on a track where they become a citizen who can contribute both to the nation as well as to the globe,” said Member of Parliament Syed Zafar Islam, a national spokesperson for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

But Gupta said “government programmes aren’t even reaching the last girl” — referring to the most disadvantaged children, such as teenage girls who are poor and very often from an oppressed caste.

Tabassum Jahan, 16, who lost her father, the sole breadwinner, to COVID-19 in May, has this plea to the authorities: “Help me and my younger siblings to continue our education.”

As the eldest of six girls and a boy, who is eight, she had to quit school to help the family earn some money by selling bangles or stitching clothes. Her aspirations have turned to ashes.

“I wish to study, achieve something and help others poorer than me,” said Tabassum, who lives in Bhagwanpur, Uttarakhand.

But like Avnish, she faces a Hobson’s choice. “I can go to school only when the situation at home is better and my younger brother and sisters get two adequate meals a day,” she said ruefully.

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.