November 7, 2021 6:20:24 am

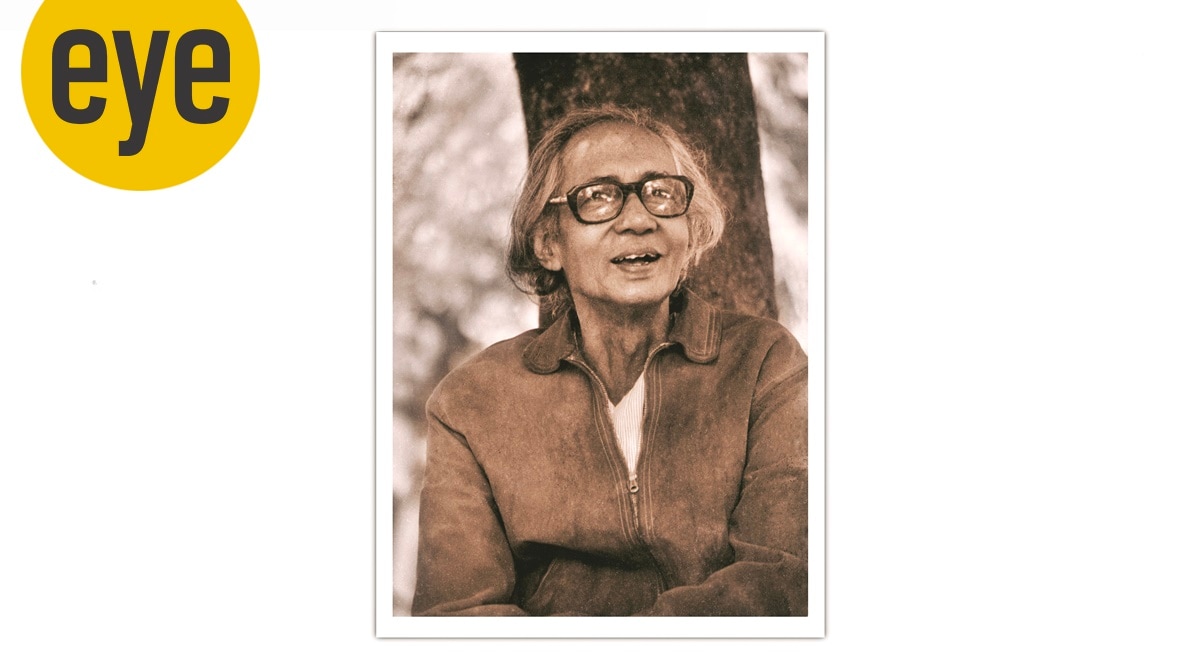

Hore was born in Barama, Chittagong, in 1921 (Source: Murali Cheeroth)

Hore was born in Barama, Chittagong, in 1921 (Source: Murali Cheeroth) By Murali Cheeroth

Wound as a word and an idea exemplifies the creative world of Somnath Hore. Both physical and philosophical at once, these are wounds that pervade the body and the soul, those inflicted by war, famine, violence and even ideologies. Hore was an artist with a deep understanding of history. The image of the “wound” was his metaphor that reflected impermanence.

Hore was born in Barama, Chittagong, in 1921, which is part of Bangladesh today. He witnessed the Japan bombing in his homeland in December 1942, when he was barely 21 years old. Within a year, another adversity struck. The Bengal famine devastated lives. Nearly three million people died or were forced to flee. Such experiences left him with severe trauma, which surfaced in his art.

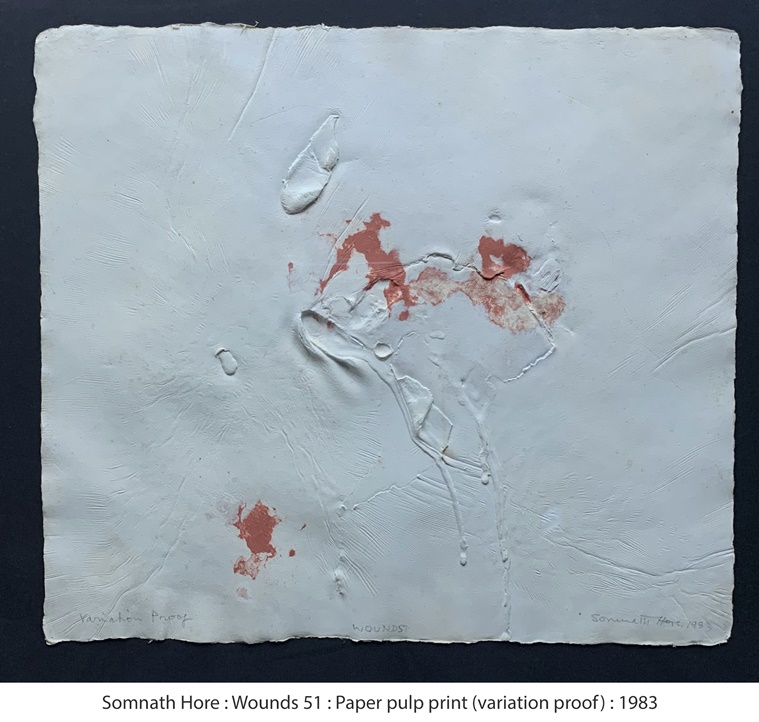

Somnath Hore’s #Wound51 artwork (Source: CIMA Gallery)

Somnath Hore’s #Wound51 artwork (Source: CIMA Gallery) Around this period, he was introduced to eminent artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, who showed him how one could express such unbearable sufferings in art. Later, the communist party assigned him to document the Tebhaga Movement, the farmers’ uprising in north Bengal, in 1946-47. Those sketches had blood marks that never dried. Wounds as an emblem of human suffering and pain began from there and, later, found its place in his sculptures, as well.

At the same time, he believed that real art cannot be a vehicle for politics, when it towed party lines. “Art may well reflect social consciousness; however, that is of small consequence,” he wrote in his quasi-autobiographical essay, My Concept of Art (The University of Chicago Press/2009).

During an informal interview with me, in 1995, he explained his engagement with wounds as a metaphor. “When I started drawing things like war, famine and riots, those were a reality before my eyes. And they have come into my work. Then, the medium which I had selected… that was somewhere similar, in the sense… like when I do woodcutting… digging the wood with a chisel or while burning the plate with some acid are also a kind of wound. So, the past, the experience and the mediums meet at a point of culmination and take you somewhere… Suppose while fixing the pieces of wax, one with another, I heat a knife and slice those wax pieces before fixing them, this treatment itself carries the sense of a wound. When I am fixing it, say a drop of heated wax is oozing out, it’s not that the drop is meant to show a teardrop, but it emerges as an expression of a wound.”

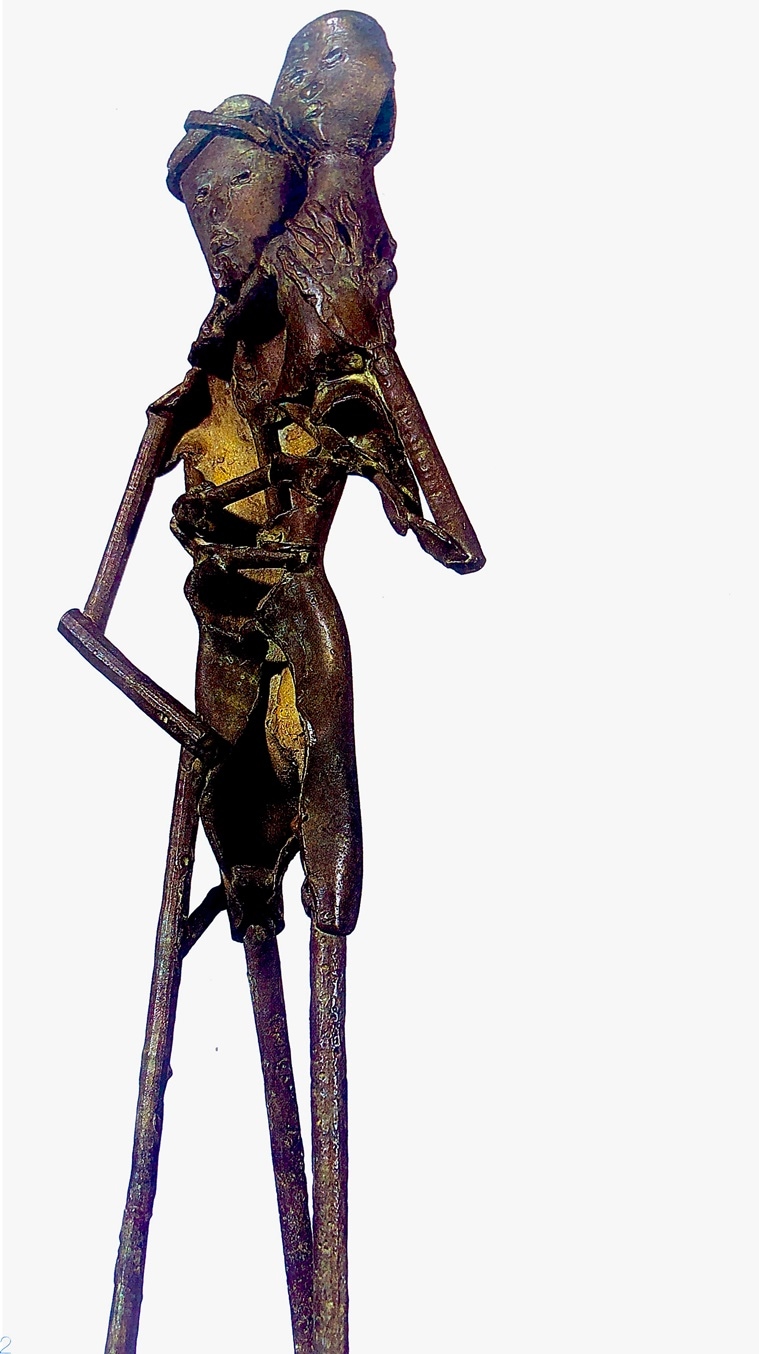

Father-and-Child-bronze-6-cm-X-14-x42.5cm (Source: Murali Cheeroth)

Father-and-Child-bronze-6-cm-X-14-x42.5cm (Source: Murali Cheeroth) The trauma of these tragedies haunted Hore so deeply that he resigned from his job as an art teacher at Indian School of Art (The Indian College of Arts and Draftsmanship), Kolkata, in 1958, and left Bengal. He joined the printmaking department at the Delhi Polytechnic, as its in-charge. This department later became the Government College of Art. It was a turning point in his career. He began experimenting with etching, aquatint and intaglio. But neither the new media nor the experiments freed the artist from the wounds within. He describes this in My Concept of Art, “During my stay in Delhi, I tried to free myself of the subject matter but the subject never let go of me. Quite unbeknownst to me, the wounds of the 1950 famine, the inhumanity of war, the horrors of the communal riots of 1946 — all these were inscribing themselves into my drawing. One would work without any preconceived notions as I chiseled the wood for my woodcuts, as I marked the metal with acid. Later, however, all those innumerable cuts and marks would bring intimations of only one subject matter — the helpless around us…”

In 1967, he resigned from the job as he found “the ambience in Delhi stifling”. Penniless, he and his wife Reba returned to Kolkata with their three-year-old daughter Chandana. What followed was a period of silence for almost two years and nobody knew what he was doing. He arrived in Santiniketan in July, 1969, thanks to his painter-friend Dinakar Kaushik. Here, he met artist Benode Behari Mukhopadhyay and sculptor-painter Ramkinkar Baij, and worked closely with them.

For him, this homecoming was in a sense an escape from the world. He began living in a modest house in the outskirts of Santiniketan. It is here that Hore explored the possibilities of sculpture as a new medium. At the same time, he continued drawing, printmaking, pulp print, lithography and engraving. But, his concern about the human predicament haunted him there as well. His paper-pulp prints, done in the ’70s, depicting gashes on an expansive white surface, have a meditative vein. These evocative impressions feature in Hore’s metal sculptures as well, where he effectively uses minimalism and abstraction.

An instance worth recalling is the portrait of Rabindranath Tagore that Hore did on the request of the West Bengal government in 1986. He had made it clear to them that it would not be like the normal portraits done in clay. They gave him a free hand and Hore brought to life the personality of the poet-guru — his boldness, sense of peace and compassion — through a semi-abstract sculpture that is still considered one of the best representations of Tagore.

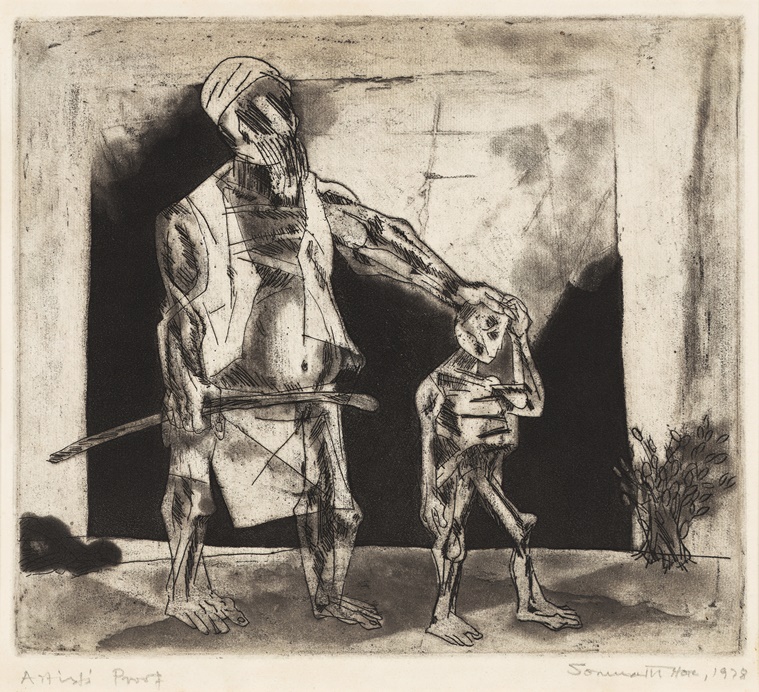

Untitled, Somnath Hore, Print, 1978 (MNF Collection)

Untitled, Somnath Hore, Print, 1978 (MNF Collection) Though Hore was not my teacher at Visva-Bharati university, Santiniketan, where I joined for Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1986 (he had retired in 1983), my interactions with him have shaped my vision. I have witnessed his wrath, as well. One such instance was when our principal at Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati university, called me to his office and said that a delegation of senior officials from US Embassy and Consulates (USEC) wanted to meet Hore. I mentioned that Somnath da seldom entertains visitors during the day, but the principal insisted that I take them along.

With great reluctance I took them to his house where one cannot reach by car. While they waited outside, I went in and apprised him about the visitors. He was visibly peeved. “Why did you bring them here?” he asked. I said nothing but reading my anxious expression, he said, “Call them in. I will tell them what I have to say.” I invited them in and made them sit in the spartan veranda. In a while he came out, draped in a shawl, looking like a sage. The officials said that USEC was planning to honour him with a fellowship and invite him to the US. While they unpacked their lucrative offer, Somnath da sat silently. Then, he pointed to the farther side and said, “There are many sculptors living over there who might suit your needs. I don’t want to leave my country, because the people here and the world around inspire me. My art takes birth from here, so kindly leave me alone.” He said this very gently. We left with a heavy heart.

I was a regular visitor to his home, but this was the first time I had such an experience. As I sat blankly under the tree at Kala Bhavana, a bicycle stopped in front of me. Somnath da, wearing his signature palm-leaf hat, stood there and called me to his side. Enveloping his hand around my neck, he asked, “Are you hurt? You know I don’t entertain visitors during the day… Murali! I never wanted to leave my country. I have seen many of my people in the organisation go out and come back. Many have not been able to write a word or draw anything since they returned. I often wonder what happened to them. I cannot leave my country till my last breath… My convictions are mine alone,” he said. As he held me close to his shoulders, he said, “Everything is time, time is recognition, even for history.” Saying this, he pedalled away, leaving me standing alone.

A santhal Mother .Bronze 13 Cmx20 x 43cm1994 (Source: Murali Cheeroth)

A santhal Mother .Bronze 13 Cmx20 x 43cm1994 (Source: Murali Cheeroth) Our meetings continued as usual. One such day, I told him about a contemporary museum project in Kerala and how they were interested in buying some of his work. He said it was good to have such institutions and how it was important for artists to have their works there.

A few days later, he called me to his house. He took a portfolio of his work and selected four rare graphic prints and wrote my name behind them. Signing them, he said, “This is for you.” It is a moment I cherish even today. Those works are currently in the permanent collection of the Madhavan Nayar Foundation’s museum in Kochi, as the gift from an artist to his disciple whom he never taught.

Murali Cheeroth is a Bengaluru-based painter, visual artist and academician

Life and Times of Somnath Hore

*Born in 1921, in the village of Barama in Chittagong. Hore lived through the Japanese bombing of WWII

*In 1943, he witnessed the ghastly famine that affected the entire Bengal. He was engaged in relief distribution and his drawings and posters often appeared in the Communist Party newspaper Janayuddha

*In 1945, he joined the Government Art College in Kolkata. He trained under artist Zainul Abedin and printmaker Saifuddin Ahmed

*In 1946, he was assigned by the Communist Party to travel across north Bengal to document the peasant’s uprising called the Tebhaga movement. The poignant diary entries and sketches have remained iconic

*Introduced to printmaking as a means to mass-produce images, Hore experimented with the medium extensively

*In the late ’50s, he moved to Delhi and took charge of the printmaking department at Delhi Polytechnic. He pursued the intaglio process of etching, and mastered the viscosity printing, applying different techniques to the same metal plate

*In 1968, he joined the printmaking department at Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan. He worked with masters such as Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij

*In the early ’70s, he started making white-on-white paper pulp prints from cement and clay that he called Wounds

*Around 1974, he started experimenting with wax discarded by students of Kala Bhavana’s sculpting department. One of his significant bronze sculptures, Mother with Child (1996), that paid homage to the people’s struggle in Vietnam, was stolen from Kala Bhavana and was never found. It left the artist disillusioned

*He later sculpted small-sized pieces, directly casting his waxwork into bronze

*After his retirement from Kala Bhavan in 1983, he lived in a modest house near a pond. He died at the age of 85 in 2006. He was honoured with a posthumous Padma Bhushan in 2007

By Vandana Kalra

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.