Another 'Botched' Execution in Oklahoma Fuels Outrage

Oklahoma ended a six-year moratorium on executions last week with a lethal injection that was experts have called "botched."

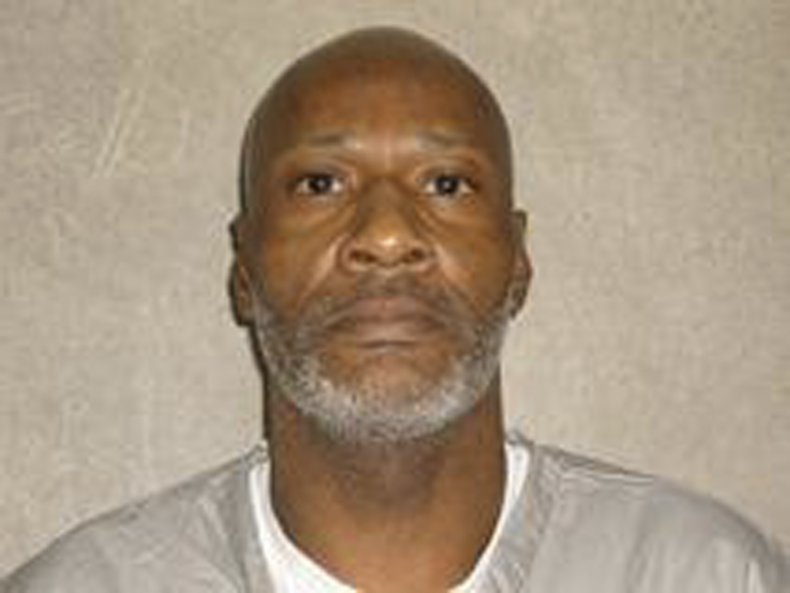

John Marion Grant, 60, convulsed repeatedly and vomited after the sedative midazolam was administered at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester on Thursday, according to the Associated Press. He was sentenced to die in 1999 for the slaying of prison worker Gay Carter.

Grant was declared dead at 4:21 p.m. after two more drugs were administered: vecuronium bromide, a paralytic, and potassium chloride, which stops the heart.

The account of Grant's execution from reporters who witnessed it differed dramatically from the version offered by the state Department of Corrections—a spokesman said it "was carried out in accordance with Oklahoma Department of Corrections' protocols and without complication."

"It's so typical for the Department of Corrections to say that what happened in the course of the botched execution... is normal procedure," Deborah Denno, a Fordham University law professor and lethal injection expert, told Newsweek. "That's simply not true."

Grant's execution was the first in Oklahoma since a series of flawed lethal injections led to a pause on capital punishment in 2015.

Richard Glossip, the lead plaintiff in the suit, had been hours away from being executed in September 2015 when officials realized they had received the wrong drug. In January that year, Oklahoma put Charles Warner to death using the wrong drug. The mix-ups came after the botched execution of Clayton Lockett in 2014. Midazolam was one of the drugs used to execute both Lockett and Warner.

The Oklahoma Department of Corrections has been contacted for additional comment.

Denno said Grant's execution served as a reminder of the need for neutral witnesses to be present at executions, particularly after Texas executed Quintin Jones earlier this year without media witnesses present. "Without reporters, we wouldn't be aware of these kinds of botches," Denno said.

Robert Dunham, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said Oklahoma is "attempting to paint a picture of an execution that has no basis in reality."

He told Newsweek: "Setting aside how blatantly false the DoC's description was, government officials have a vested interest in the execution appearing to have been normal. That vested interest will color both their perceptions and their descriptions. That's why even in the best of times, it's important to have neutral media witnesses there."

Dunham said Oklahoma's rush to execute inmates despite a pending lawsuit challenging the state's lethal injection protocols shows the state is determined to "kill prisoners now" and "willing to do so in a manner that provides an end run around judicial review."

He added the state's conduct will serve as "additional ammunition" to death penalty opponents arguing that states can't be trusted with the death penalty.

Abraham Bonowitz, the director of Death Penalty Action, was outside the prison when Grant was executed. "It's clear that governments can't be trusted with the death penalty," he told Newsweek. "And I'm not only talking about the lengths they will go to to carry out executions unlawfully."

He added: "The discussion should not be the mechanism for killing our prisoners, but that we are allowing executions at all when the criminal legal system is as broken as it is."

The state went ahead with carrying out his death sentence after the Supreme Court voted 5-3 to lift stays put in place for Grant and another death row inmate, Julius Jones, by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Oklahoma's Pardon and Parole Board on Monday recommended that Gov. Kevin Stitt spare Jones' life, but he has yet to announce a decision.

The appeals court had ordered both Grant and Jones to be reinstated in the lawsuit challenging Oklahoma's lethal injection protocols, which argues the three-drug method violates the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. A trial in that challenge is set to begin in February.

The Department of Corrections' account that Grant's execution was not botched could bolster the lawsuit challenging the state's execution protocol, Dunham said.

"One of two things is true: either they lied and the Department of Corrections can't be trusted or they told the truth and the protocol can't be trusted," he said.

Dunham said Oklahoma went ahead with its three-drug protocol despite the evidence that has emerged about midozolam since the state put executions on hold.

"The autopsy data consistently shows that prisoners who are executed with midazolam suffer flash pulmonary edema, which is a very quick buildup of fluid in the lungs," he said. "The Oklahoma federal judge described the three-drug midazolam execution as producing sensations akin to waterboarding, suffocation, and experiencing chemical fire. So all of that was known and Oklahoma went ahead anyway."

Dale Baich, an attorney for some of the inmates in the lawsuit challenging the state's lethal injection protocols, said the eyewitness accounts of Grant's execution show Oklahoma's protocol isn't working as it was designed.

"This is why the Tenth Circuit stayed John Grant's execution and this is why the U.S. Supreme Court should not have lifted the stay," Baich said. "There should be no more executions in Oklahoma until we go to trial in February to address the state's problematic lethal injection protocol."

Denno said she expects additional lawsuits to be filed following Grant's execution. "It's pretty clear that Oklahoma time and again, has had this incredibly troubling history of bungling executions and it makes it more urgent for states to develop a complete and detailed protocol," she said.

"It's actually no longer a mistake. It's a pattern and it's a predictable pattern. We know that these mistakes happen every time and that they'll happen again."