Queen's Brian May and Photo Historian Denis Pellerin Explore Stereoscopy's Origins in New Book

When he is not recording or touring as a member of the famed British rock band Queen, guitarist Brian May engages in another endeavor that is as dear to him as music: stereoscopy, the technique of seeing two almost identical photographs together through a viewer called a stereoscope to produce the illusion of 3D.

Over a decade ago, May resurrected the London Stereoscopic Company, which first came into existence in the 1850s as a seller of stereoscopes and stereo images (a.k.a. stereographs or stereos). Under May's stewardship, the reborn company maintains a website with information about stereoscopy and publishes books ranging from the 19th-century photographic works of T.R. Williams (A Village Lost and Found) to archival images of Queen (Queen in 3-D).

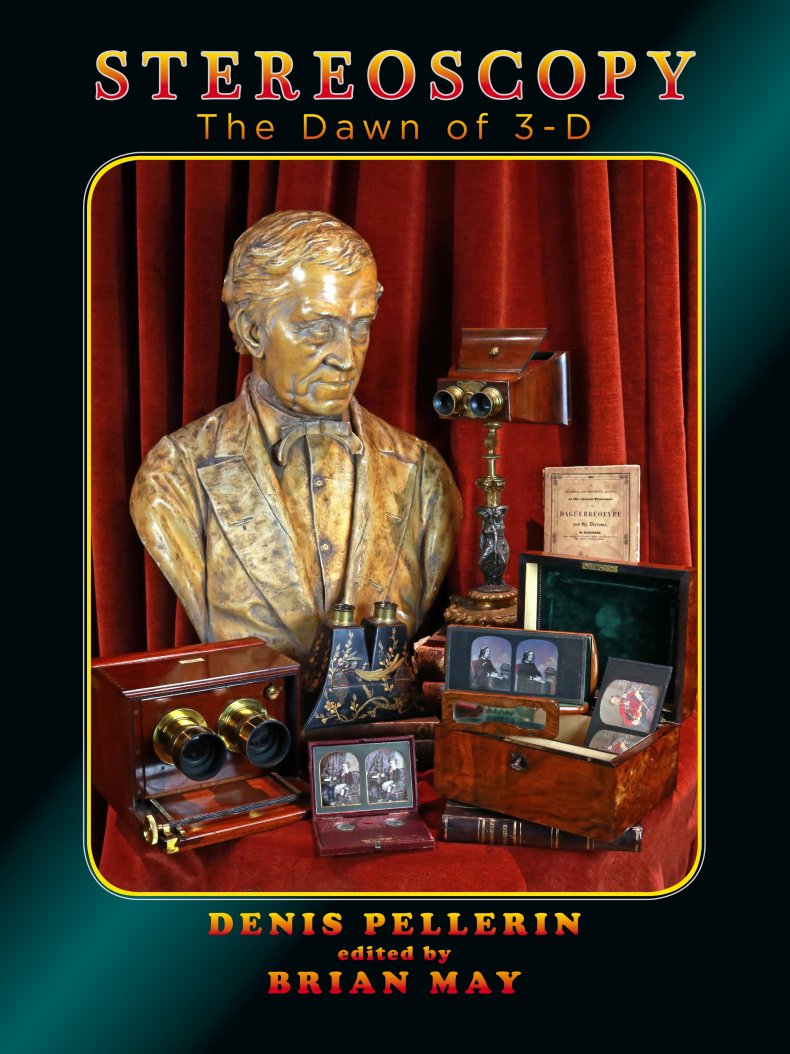

The London Stereoscopic Company's latest book focuses on the history of stereoscopy itself. Written by photo historian Denis Pellerin and edited by May, Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D traces the beginnings of stereoscopy during the Victorian era. Among its highlights are the British scientists/inventors Charles Wheatstone and David Brewster who played pivotal roles in the development of the stereoscope; the history of the original London Stereoscopic Company; and the popularity of stereoscopy due to the mass production of stereographs. It is also illustrated with scans of vintage stereographs that the reader can see in 3D with an OWL viewer designed by May and included with the book.

"It's the book that I wanted to put out since we began the London Stereoscopic Company," May tells Newsweek. "I wanted the birth of stereoscopy to be documented because they've never been documented really truthfully."

Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D attempts to dispel the inaccuracies and myths associated with stereoscopy's history. For Pellerin, the book was approximately 15 years in the making.

"When I started studying the history of stereoscopy," he says, "I found things that didn't sound right. There were stories about the beginning of stereoscopy, and of course, the famous myth about David Brewster giving a stereoscope to Queen Victoria—and suddenly thousands of stereoscopes were sold. I found that a bit fishy and not in keeping with what I knew about the Victorians."

About 30 years ago, Pellerin contacted the royal archives and asked them if they had the actual stereoscope that Brewster gave to the queen, as reported by the press at the time.

"They said, 'No, we haven't got it. We haven't got any trace of such a present,'" The historian later recalled. "I was in France at the time, so it was difficult to do any search. That was before the internet was something big and you could find information online. As soon as I arrived here [in Britain], I said, 'I need to find out what really happened.' And that's how we began."

The new book documents Charles Wheatstone as the inventor of the stereoscope.

"It revolves around the genius of Wheatstone," says May. "He actually figured out what none of the geniuses of the Renaissance did: the fact that we have two eyes in order to achieve stereopsis, which gives us an in-depth view of the world. I think he's a true genius and he's never really been celebrated in the way that he should be. So this is kind of putting Wheatstone in the place where he belongs."

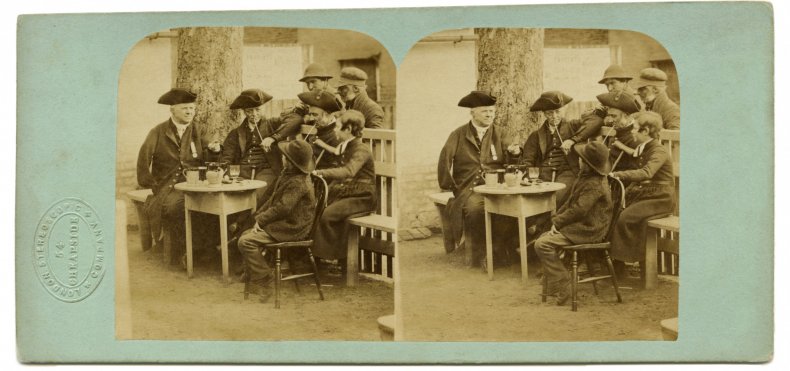

Stereoscopy was hugely popular during the Victorian period, especially in the 1850s, as the public became fascinated with stereo images ranging from portraits to famous places through the perspective of 3D. One of the reasons behind the fad, according to Pellerin, was that stereographs were the first photos actually owned by people.

"They could buy them, own them, keep them, look at them, show them to their friends, And of course, they were in 3D. It was a way to travel without any risks, any dangers. You didn't need a passport. You could visit the whole world. As early as 1859, there were photos of Japan, China, the States, all of Europe. There was a craze because people wanted to know more, they got curious and they wanted to see things: animals, famous people and whatever."

Stereo photography was the precursor to the more popular forms of 3D about a century later, from the View-Master toy to virtual reality. Yet stereoscopy's historical importance has never gotten its proper due.

"It became so huge," says May. "People don't realize—in the 1850s, stereoscopy was the biggest thing. There was no TV, no films, no radio, no Internet. Stereoscopy was the thing. Everybody pretty much had a stereoscope in their home. The motto of the original London Stereoscopic Company was 'No home without a stereoscope,' and they more or less got it."

"It's very strange that stereoscopy was never studied before," says Pellerin, "because it was overlooked by a lot of historians and academics. They said it was commercial. Really? What is not commercial? [Stereos] were there to entertain people, and for some reason, a lot of historians just rejected that and said, 'Well, they are not important because they are just entertainment.' And it's totally wrong. There are literally millions of stereos, and they tell the whole history of the second half of the 19th century and even later because we have thousands of stereos in the First World War."

Like all fads, stereoscopy eventually declined in popularity. For stereoscopy, its fall came by the 1880s as the cartes-de-visite became the new phenomenon—they could be considered, according to Pellerin, the ancestor of the selfie.

"People suddenly could have their own photo. Because it was not very expensive, they could actually buy lots of them, give them away to their friends: 'I give you my portrait, you give me your portrait.' So they had albums and they mixed celebrities and family and friends in the same albums. That's what actually killed the first Golden Age of Stereoscopy because of that."

Today, May, Pellerin and the London Stereoscopic Company are preserving the memory of vintage stereo photography; May himself owns a collection of rare stereographs.

"To me, it's a very exciting thing," the guitarist says. "I love bringing this fascinating and illuminating way of documenting things into the 21st century. I'm achieving a lot of success and hearing a lot of 'wows.' Everybody's blown away, including a lot of my friends in NASA, who I work with on making astronomical stereos."

"He was about 10 or 11 when he started really getting interested in stereos and taking his first stereo himself," Pellerin says of May. "The magic has never left him. He has seen millions of photos just like I have. When I see he's a bit down or whatever, I just have to tell him, 'Okay, Brian, I've got some photos to show you.' And suddenly he becomes this 11-year-old again. That's amazing because his passion has never left him. He still feels the magic of stereo."

Meanwhile, May and Pellerin are embarking on a new book project about a pioneer in stereo photography from the 19th century.

"There's one more book which I have to write before I pop off," says May, "and that is the other half of the T.R. Williams story, because A Village Lost and Found [which the London Stereoscopic Company already published in 2009] is all about his series 'Scenes in Our Village.' It's already mapped out, but I have to finish that book. I'm doing it with the help of Denis, who is my wonderful curator and photo historian. I'm very excited about Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D. It's this book that had to be written."

A virtual book launch for 'Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D,' featuring Brian May and Denis Pellerin, will take place on November 10. For information, click here.