Jurassic Park, and the diabolically sumptuous pleasure of watching dinosaurs enjoy a human feast

To see a couple of privileged folk, frantically trying to scramble their way to safety, their faces whiter than their original white after what they have just seen. It is oddly satisfying to see how it ends for them, because I know it will.

When the going gets tough, we turn to our favourite guilty pleasures. But when entertainment is concerned, is there even any guilt to what gives one pleasure? In our new series Pleasure Without Guilt, we look at pop offerings that have been dissed by the culture police but continue to endure as beacons of unadulterated pleasure.

***

A dusty single-screen theatre in a cold corner of Shimla, speckled with a history of fire hazards and creaking balconies. For the first time, it is teeming with children who are fascinated by what they are watching even if they do not understand what they are watching. Some squirm, others shriek, and some, like me, even climb onto the seats and cheer; not because I understand what is happening but because of the sheer wondrousness of what I am 'experiencing.' I am a primary school kid, there with my classmates on a school trip. Theatre going is an experience reserved for adults, for people who require the interventions of love, romance, comedy, and rebellion. To us kids, this is new.

I watched Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park as a first-grader, in the dingy, now-lapsed Rivoli in Shimla. The utter smashing fun of watching these impossibly alien creatures terrorise fellow humans has since never lost its charm.

If I am asked to look back to a cinematic moment that etched the power of cinema in my brain, it would not be a Tarkovskian frame or an RD Burman number, as iconic as they might be; but the sight of a glass full of water, shaking, little ripples forming in its belly by the far-off thuds of a monster no human had contemplated before. Spielberg’s film, which came out in 1993 but was belatedly shown in cinemas in my hometown the following year, is to me, a cookie-cutting moment in the history, of not just world cinema, but Indian cinema. Theatres I remember were full from the morning onwards. I watched the film thrice, unsure at the end of it all, of what exactly it was that I had seen. And therein perhaps lies Jurassic Park’s importance, of creating a language, a narrative structure and scale that preceded any native anxieties about making a ‘global’ film. Film-going had suddenly turned into a spectacle, a festival of sorts.

To people, like me, who grew up in small towns before the internet invaded our juvenile borders with the wisdom of the world, quality cinema meant access to what had been watched and approved by metropolitan towns. In many ways, Jurassic Park is perhaps also the biggest global blockbuster of a post-globalised India. Cinema became universal overnight. Indian theatres suddenly saw value in screening English cinema, and it pushed open doors to other films that we could not have anticipated ahead of time. In smaller towns, cinema was often coupled with anti-social elements — people with too much time or money or their hands; not something the ‘cultured’ or the ‘mannered’ would do over a weekend. The arrival of global blockbusters, like Jurassic Park, turned obscure theatres into events too big to ignore. Even my father, who continues to deride the very idea of cinema, accompanied me to one of the shows.

Spielberg is of course known for inventing the summer blockbuster with his first breakout hit Jaws. He is perhaps the first director to see cinema through the lens of science and geography on scales that were only conceivable through the lens of war. In many ways, the Jurassic Park films are, in fact, like rides inside an amusement park. Narratively, they combine wonder, dread, withdrawal, and escape in just the right amount so you come out sweating, hooting, and feeling you have been on a ride. Spielberg might also be the world’s most popular proponent of environmentalism. All his films teach us to not screw around with nature.

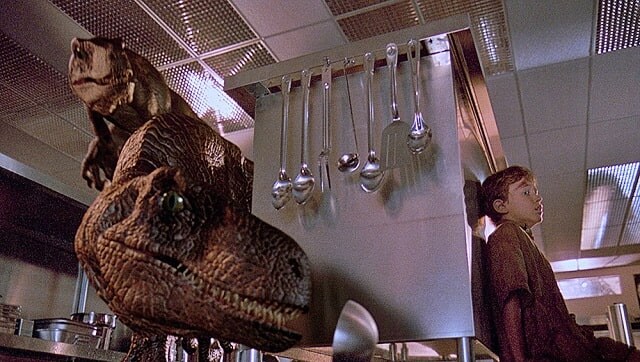

But what made me sit up as a kid while watching Jurassic Park was the baffling life-like monsters that, it seemed, the filmmakers had created through sheer imagination. Watching them trample, chew, and sling humans around like tennis balls was both hair-raising and fun. As I have grown older, that aspect of all the Jurassic Park films has retained its charm for me.

Nothing like an unsuspecting, languorous greedy white guy who is about to be chewed by a cunning Velociraptor (my favourite creature of the lot).

As is Spielberg’s forte, the man vs wild conflict, that most of us never experience, became an adventure worthy of the experience, however facile and made-up its particulars. It is a cinematic adventure like no other, and I simply cannot help myself but be on one.

This love for gigantic, man-eating creatures has since Jurassic Park extended to other films that are, of course, inspired by Spielberg’s narrative handbook – like Godzilla. The Jurassic Park films themselves have lost their sheen after kicking the bucket too soon, and losing in its attempt to serialise the acceptance of dinosaurs, its novelty and fearfulness. Dinosaurs simply do not inspire as much dread since they have been domesticated and traded as just about any other animal that man finds a way to colonise. Irrfan Khan’s appearance in the franchise makes it that much more special for a viewer sitting in India, but the films themselves have dried up in terms of ideas and the sheer otherworldliness that Spielberg’s first evoked.

On one end, these are murderous, brutal killing monsters. But despite its primacy, the dino-eat-man world of Jurassic Park is just too outrageously fun, and maybe entertaining rebuke against capitalism – if there exists that sort of thing. Nevertheless, I watch Dino mania, as I like to call it, every time it is on offer. It is a world so outrageously simple and yet intimately affecting for the child in me who still wants to believe. Especially when it is a couple of privileged folk, frantically trying to scramble their way to safety, their faces whiter than their original white after what they have just seen. It is oddly satisfying to see how it ends for them, because I know it will. Even the predictably cruelty of a baby T-rex, in this context, is adorably rebellious. So much so I wish some of them were around.

Read more from the 'Pleasure Without Guilt' series here.

Manik Sharma writes on art and culture, cinema, books, and everything in between.

also read

Dave Chappelle’s new Netflix Special 'doesn’t cross the line on hate', top exec says despite controversy

Netflix said will Dave Chappelle’s The Closer will remain on the streaming service despite criticism over comedian’s remarks about the transgender community

Britney Spears thanks #FreeBritney supporters after dad's suspension from her conservatorship

Singer-songwriter Britney Spears expressed gratitude to her fans for their "constant resilience in freeing me from my conservatorship."

Cinema is full of clichés — but as clichés ourselves, should we not celebrate that?

Attack of the Hollywood Cliches, a new Netflix documentary, mocks the cliches that cinema is riddled with. But let's face this: What is more clichéd right now than the nine-to-six, backbreaking, laptop-hugging jobs most people streaming this documentary are doing?