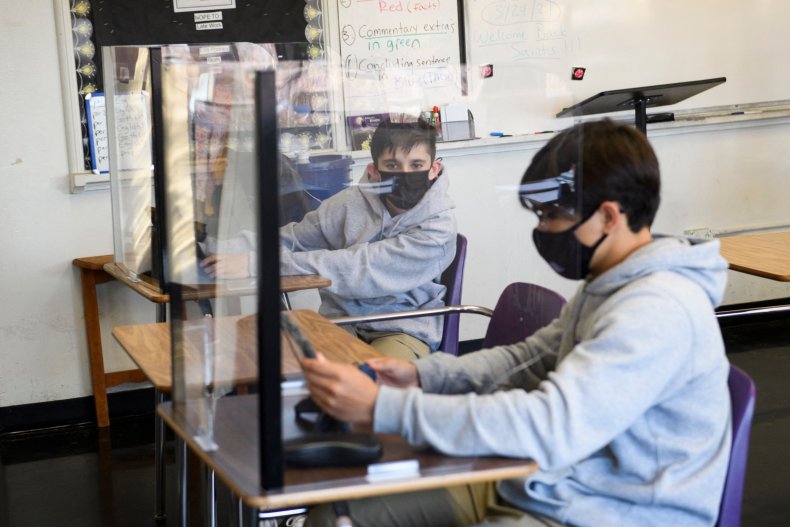

Plexiglass Dividers at Work Won't Protect You From Delta, Says Expert

A University of Minnesota aerosol scientist has said plexiglass dividers offer limited protection from Delta, the dominant COVID-19 strain in the U.S. for office workers as employers attempt to make workplaces secure for their employees.

Professor Chris Hogan cast doubt on the effectiveness of using plexiglass in offices as it could offer limited protection from COVID-19 variants.

Speaking to KVUE, Hogan said: "The dividers are...sneeze guards. A decent proxy for it is when we used to have smoking and non-smoking sections in restaurants. There would be the occasional restaurant that would do this with a divider, and you knew that you could smell smoke in the non-smoking section if you were right next to it."

He continued to tell the outlet the dividers were useful at places such as checkouts as face-to-face interaction is limited, but settings where the COVID aerosols have time to remain would limit the plexiglass' effectiveness.

The professor then encouraged employees to learn more about ventilation systems at their workplace, especially if they worked there for long periods at a time.

Hogan continued to tell KVUE: "One of the things that you can ask about is the air changes per hour, ACH, in the office space where you work. This is the number of times per hour that the air in that space is kind of swept out and replaced. They often aim for an ACH of around four in modern offices. More in bathrooms and higher in lunchrooms."

He later added other technology could be used to better protect workers in offices and that it had already been adopted by some employers.

The professor continued to tell the outlet: "One technology gaining more popularity in buildings involves UV lights that help inactivate viruses. [...] We did a study of what's called in-duct UVC light, inside a duct, and you would pass airflow through."

Hogan added: "Only one out of every 10,000 viruses that went in, was still infectious at the outlet."

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (USFDA), UVC radiation "can only inactive a virus if the virus is directly exposed to the radiation."

It added: "UVC is commonly used inside air ducts to disinfect the air. This is the safest way to employ UVC radiation because direct UVC exposure to human skin or eyes may cause injuries and installation of UVC within an air duct is less likely to cause exposure to skin and eyes,"

The USFDA did admit, however, "there is limited published data about the wavelength dose and duration of UVC radiation required to inactive the SARS-CoV-2 virus."

But, with the more contagious Delta variant now the dominant strain of COVID-19 in the U.S., Hogan said there were other effective low-tech ways to keep workers safe from the virus.

He encouraged workers to wear face masks and maintain social distancing while also improving ventilation by opening windows and by also working remotely if possible.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recommends improved ventilation in buildings as a way to combat the spread of COVID-19 in the workplace as one of several measures to protect workers from becoming ill.

In a June 2 update, the CDC said SARS-CoV-2 viral particles spread between people more readily indoors than outdoors. Indoors, the concentration of viral particles is often higher than outdoors, where even a light wind can rapidly reduce concentrations.

"When indoors, ventilation mitigation strategies can help reduce viral particle concentration. The lower the concentration, the less likely viral particles can be inhaled into the lungs (potentially lowering the inhaled dose) contact eyes, nose and mouth or fall out of the air to accumulate on surfaces."

It continued: "Protective ventilation practices and interventions can reduce the airborne concentrations and reduce the overall viral dose to occupants."

Newsweek has contacted Plexiglas and Hogan for comment.