The first presidential election in India after Independence was held on May 2, 1952. After four days of the election, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, with 5,07,400 votes, was declared the winner. In 1957, he won the election for the second time and to date, he is the only person to hold the President’s office for two terms. The first four presidential elections were held in May, however, since 1977, the polls for the same have shifted to July.

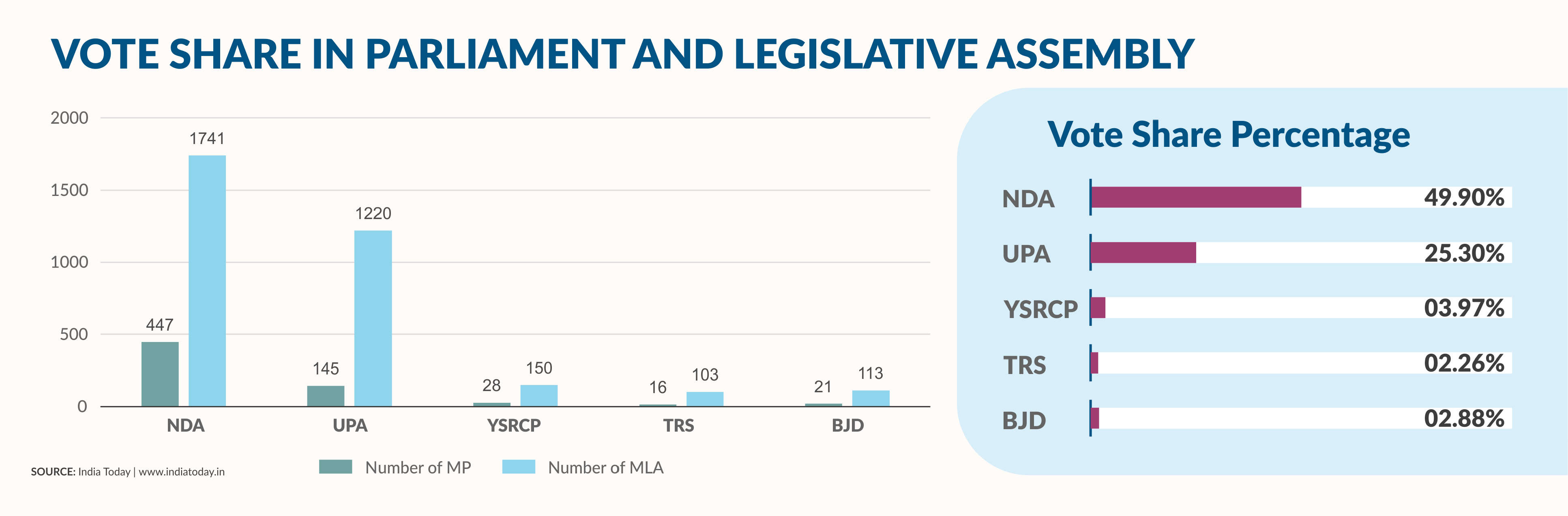

The 2022 presidential election will be the 16th presidential election to be held in India.The term of President Ram Nath Kovind is set to end on 25 July 25, 2022. The next presidential election is scheduled to be held in mid-July next year after polls to five state assemblies – Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Manipur, and Goa – are concluded. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which currently enjoys a majority in the Lok Sabha holds 49.9% of the electoral college, while the Indian National Congress (INC) led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) holds around 25.3% of the electoral college.

HOW IS THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA ELECTED?

As per Article 56(1) of the Constitution of India, the President of India shall only remain in office for a period of five years. The Election Commission of India is responsible for conducting the election to the offices of the President and the Vice-President. The qualifications required to be eligible for election to the office of the President are: (i) The candidate must be a citizen of India; (ii) should be 35 years of age or above; and (iii) should be qualified to become a member of the Lok Sabha.

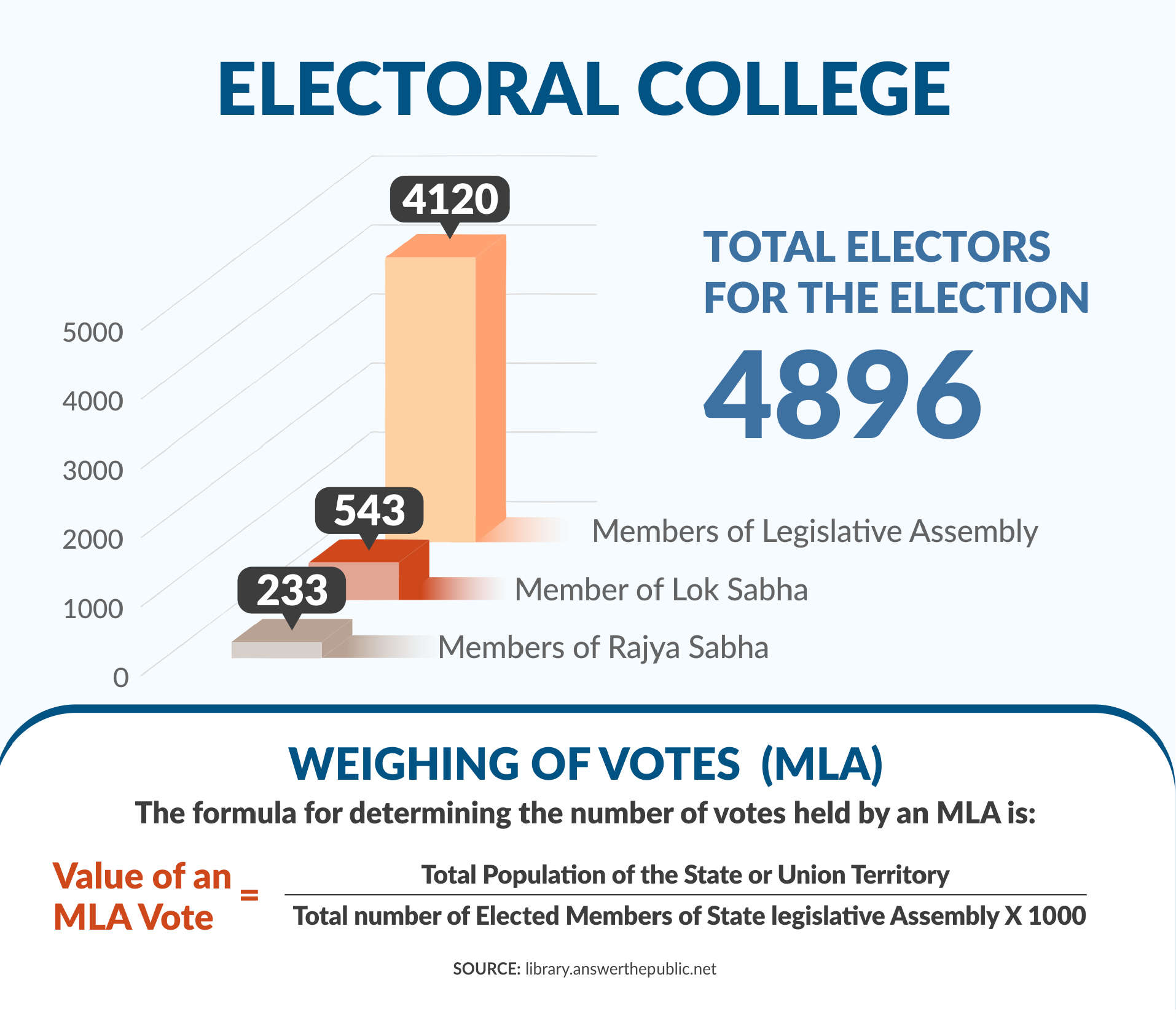

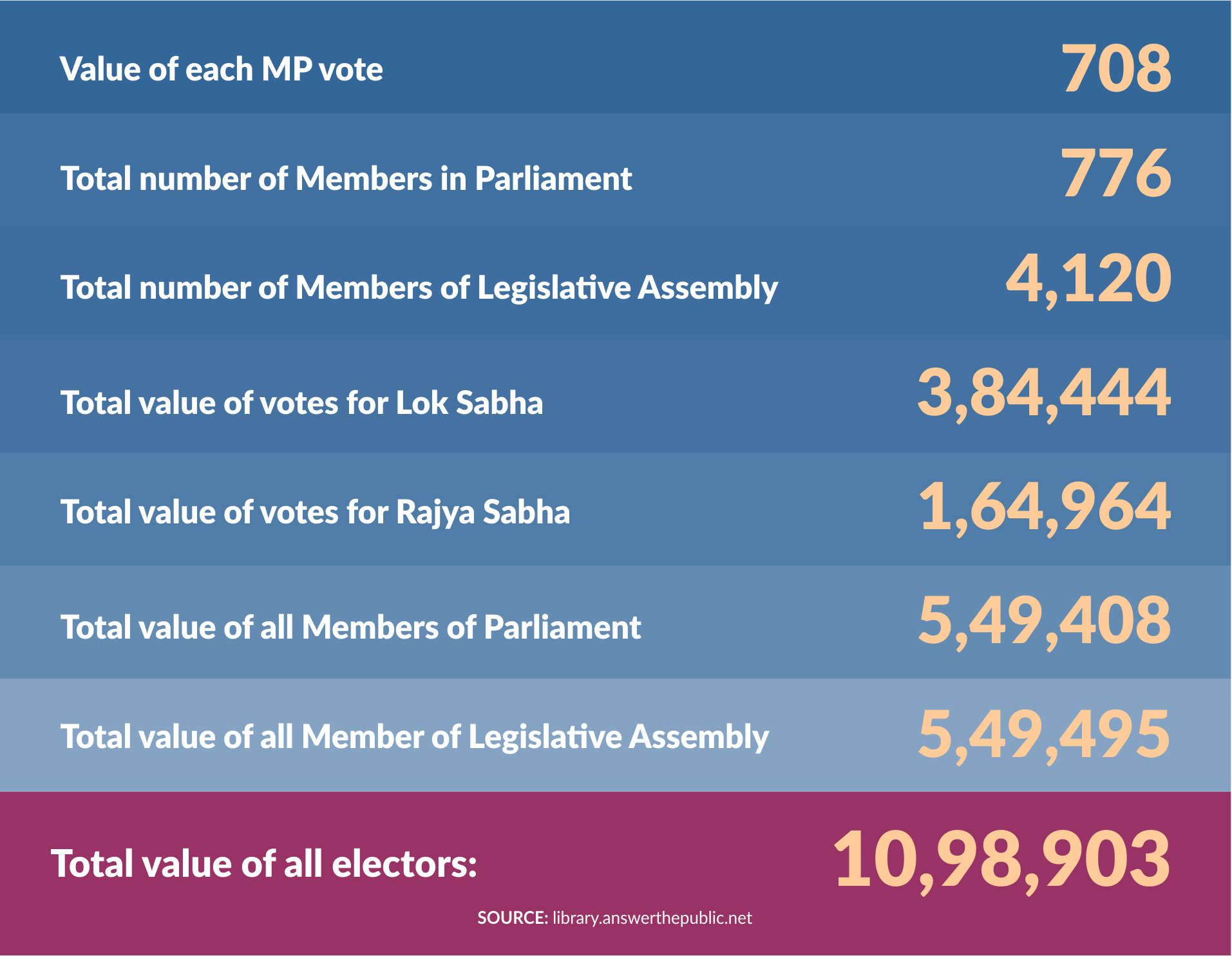

The President of India is indirectly elected by an electoral college consisting of the elected members of both the houses of Parliament, the elected members of the Legislative Assemblies of the 28 states, and the elected members of the legislative assemblies of the Union Territories of Delhi, Puducherry, and Jammu and Kashmir. The 12 nominated members of the Rajya Sabha are not allowed to vote for the Presidential elections. This means that 4,120 members of legislative assemblies and 776 members of Parliament elect the President. As per the electoral college system, the value of votes that each Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) and Member of Parliament (MP) has varies as per the population of the state. This simply means that the value of an MLA’s vote will vary from state to state in order to reflect the population of each state. A simple formula is used to calculate the same. The total population of the state (as per the 1971 census) is divided by the total number of MLAs in the state and then multiplied by 1,000. For instance, the value of one MLAs vote in Delhi is 58, 208 in Uttar Pradesh, and only 7 in Sikkim. The value of the vote of a member of parliament is the same across Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha – 708. The total value of votes of all elected MLAs and MPs gives the final number of votes in the electoral college, which is 10,98,903.

A secret ballot under the transferable vote system is used to elect the President of India. Each MLA and MP ranks the presidential candidates in their order of preference, and the candidate with the lowest number of votes will drop out. Votes given to this candidate are then redistributed based on the next preference, and this goes on until one candidate secures the needed majority. In order to win, a candidate must have more than 50% of the votes.

BJP AND NDA’S LANDSCAPE IN 2022

The BJP-led NDA does not currently enjoy a majority in the Rajya Sabha and has lost power in some important states such as Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand, and faced defeat in the high stakes West Bengal Assembly Elections. It has also lost some key allies such as the Shiv Sena and the Akali Dal. In 2017, when the NDA fielded its candidate, the current President of India, Ram Nath Kovind, BJP and its allies ruled over 70% of the country, but now its national footprint is down to around 45%. While the importance of the BJP and its allies have diminished in both the Houses of the Parliament, Assembly Elections scheduled in key states such as Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Manipur, and Goa scheduled to happen before the 2022 Presidential elections, will have a major impact on the NDA’s tally.

Currently, the NDA has 334 members (out of 540 members) in the Lok Sabha and 116 members in the Rajya Samba (out of 232 members). The nominated members of the NDA can not vote in the Presidential elections. Given the total value of the electoral college (10.9 lakh points), NDA has around 5,42,957 votes, which comprises around 49.9% of the electoral college. The UPA consisting of the INC, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), and Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) has around 2,74,655 votes, which is around 25.3%. Others, including some major regional and state parties, have around 24.8% of the votes. This last section has majorly three different kinds of parties. The first category has parties that directly align with the Congress. The second category includes parties such as the All India Trinamool Congress (TMC), Left, Shiv Sena, Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM): these are parties that oppose the BJP, and could potentially align with the Congress just to ensure the loss of the BJP.

The third category includes important regional players such as the Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP) of Andhra Pradesh, the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) of Odisha and the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) of Telangana. These regional parties hold a vote share of 9.1%. Given this, it is clear that both the NDA and the UPA would aim to gather the support of parties such as YSRCP, BJD and TRC during the upcoming elections. YSRCP holds 3.97% of the vote share, while BJP holds 2.88% of the vote share and TRS holds around 2.27% of the vote share.

If the NDA manages to get the support of the third category of regional parties (around 9.1%), its vote share would increase to 59%, giving it a comfortable winning majority. Similarly, if the UPA alliance manages to win the support of this category of parties, it would increase its vote share to 51.1%. While this would be a narrow margin of victory, as the NDA currently has 49.9%, it would still be ahead.

Photographs from Wikimedia Commons

WHAT IMPACT COULD THE 2022 ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS HAVE ON THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION?

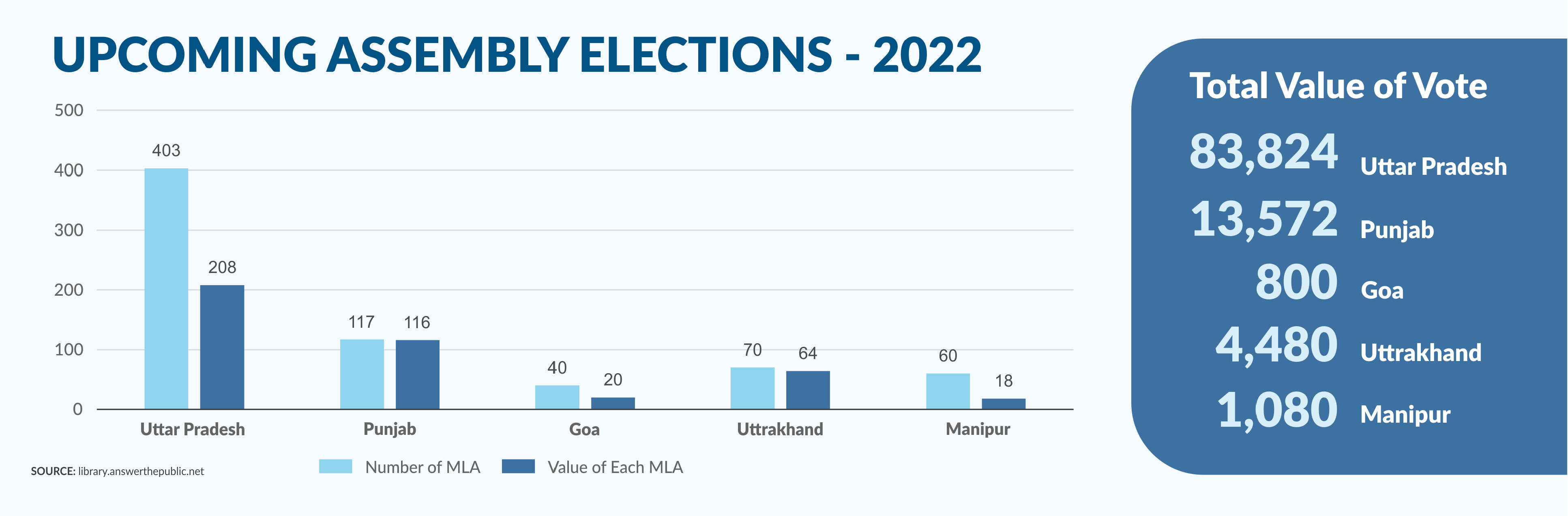

Given the current scenario, the NDA is slightly short of a majority. However, this includes the alliance MLAs and MPs in states such as Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Goa, and Manipur, all of which are set to go to polls early next year before the Presidential elections. The INC is in power in Punjab, which will also be heading to the polls at the same time next year. In Punjab, each of the 117 MLAs has a vote value of 116, out of which only two MLAs are from the BJP. Given the NDA and SAD’s decision to part ways with each other, and the unrest due to the farmer’s protests ongoing in the state, it is unlikely that the NDA will be able to increase its tally in the state significantly. Uttarakhand has 70 MLAs with a vote value of 64 each and a total value of 4480. While the BJP is currently in power in Uttarakhand, the political crisis in the state and high anti-incumbency will prove to be a challenge for the BJP to win back the state in 2022.

Due to the population of Goa and Manipur, these states do not carry a significant vote value in the electoral college. Manipur has 60 MLAs with a vote value of 18, and their total value is only 1080. Similarly, Goa has 40 MLA’s with a vote value of 20 each making the total vote value 800. Uttar Pradesh has the highest vote value of five states going to the polls. Given that there are 403 MLAs from UP, it holds a vote value of 83,824 or 15.25% of the votes of state MLA’s in the electoral college. Currently, the NDA has 304 BJP MLAs and 9 MLAs from the Apna Dal. Any change in the number of MLAs the NDA currently has in UP, could have a domino effect on the Presidential vote, due to the high value of votes of each MLA from UP. If the BJP wins the state by a smaller margin, the value of opposition parties and parties on the fence will increase. While the party will still be able to win the electoral college vote, even if its margin reduces in poll-bound states, the upcoming elections will influence the bargaining power of the opposition and other parties.

The Daily Guardian is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@thedailyguardian) and stay updated with the latest headlines.

For the latest news Download The Daily Guardian App.

File photo of PM Narendra Modi with Donald Trump.

File photo of PM Narendra Modi with Donald Trump. File photo of Vladimir Putin, Narendra Modi and with Xi Jinping.

File photo of Vladimir Putin, Narendra Modi and with Xi Jinping.