Former Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee (Right) and Chief Economic Adviser Kaushik Basu at JFK airport lounge in New York, en route to Delhi. (File)

Former Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee (Right) and Chief Economic Adviser Kaushik Basu at JFK airport lounge in New York, en route to Delhi. (File) Writing a diary is easy. Reading a diary, however, has massive odds stacked against it. Comedian David Sedaris has warned: “If you read somebody’s diary, you get what you deserve.”

Part of the problem is that most people live rather repetitive lives — and, indeed, equate it with everything they value such as stability, continuity, and maturity. Consequently, the diary entries reflect that. British politician Enoch Powell said he never wrote a diary because keeping one “is like returning to one’s own vomit”.

But these unscientific generalisations can be suspended if the writer of the diary is a brilliant and curious economist, with a massive breadth of interests, who is recounting his experiences as a policymaker in the world’s largest democracy during a period when that economy and the society and polity were almost shifting shape. That is the promise of this book.

Kaushik Basu, professor of Economics at Cornell University, the US, shares his diary entries from 2009 to 2016 — the period during which he took a break from his life as an academic and focussed on being a policymaker. He first served as the chief economic adviser to the Indian government (2009-12) and then as the chief economist of the World Bank (2012-16).

For most Indian readers then, the first half of the book, dealing with when Basu was the chief economic adviser, is the really interesting part. The period between 2009 and 2012 was quite a remarkable one for India. On the economic front, 2009 became a watershed year as India started losing its fast growth momentum, and, by 2012, the economy had completely run out of steam. Investments by businesses — possibly the best marker of whether an economy can sustain a fast GDP growth rate — have not recovered since, even as all other metrics such as individual consumption, exports, the health of the banking system, employment levels, etc. have also petered out. The United Progressive Alliance UPA) II was characterised by decelerating growth and accelerating prices.

Politically, it saw the surprise return of prime minister Manmohan Singh-led UPA government and its rather quick decline in popularity, all within three years. By the end of 2012, it was clear that the UPA had lost most of its political credibility.

Socially, the steady stream of corruption allegations against public officials didn’t just erode the consensus around a liberal democratic order but also set many Indians towards the path of extreme Hindu nationalism.

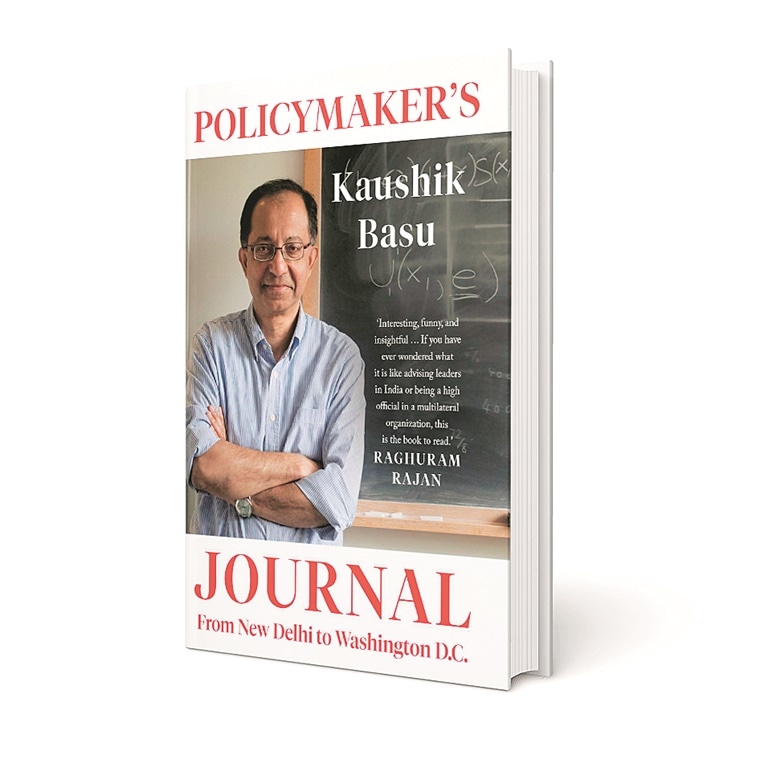

Policymaker’s Journal: From New Delhi to Washington D.C.

Policymaker’s Journal: From New Delhi to Washington D.C.By Kaushik Basu

Simon and Schuster

384 pages

`699

It is another matter that a decade later, many now look back at that humbling phase of national life quite wistfully. In that sense, the book is quite timely as well.

So, what was the view from the inside? How and why did the UPA allow such a fast slide, more so on the economic front, and especially since it was being led by a

top economist?

Being essentially a collection of diary entries, Basu’s book is neither intended to address any such direct query nor does it provide a clear compact answer. But reading it will reintroduce many to the not-so-vague helplessness that abounded policymaking in that era.

For instance, there are far too many diary entries that start with PM Singh summoning Basu to ask what can be done to bring down inflation. Basu does his best to tell readers that once set in motion, the wheels of inflation are not easy to stop and that the actions of the Union government alone are not responsible for spiking prices; other factors also play a part.

But these provide cold comfort even a decade later. Sample this entry from October 15, 2011, recounting PM Singh’s meeting on inflation with D Subbarao (then RBI governor), Saumitra Chaudhuri (from former Planning Commission member), C Rangarajan (then chairman of the PM’s Economic Advisory Council), Montek Singh Ahluwalia (then deputy chairman of the Planning Commission) and Basu. “The quality of the discussion was first rate. It is not difficult to see why through all the ups and downs, India’s economy has, overall, done so well in recent times,” writes Basu, as he ends recounting.

The fact is, as mentioned earlier, during this period the Indian economy was running aground, sustaining structural damage (such as, the growth of bad loans in the banking system) that continues to impede its movement even now — thanks, in part, to the equally inept economic management by the Narendra Modi government that succeeded the UPA.

Similarly, on November 19, 2011, Basu notes that “India is clearly on the verge of a major economic take-off, unless political stupidity derails us.” Again, in reality, the Indian economy continued to decelerate for another two years since that date.

Hindsight is indeed 20-20 but then this book, if not that diary, does not reflect that clarity of vision. There is a distinct sense that things were just as good as they could be because if they could be better, then they would have been. “I am a determinist. I believe that all creatures are fully determined by their genetic make-up and environmental influence. In other words, human beings live scripted lives,” writes Basu, on the eve of India’s Independence Day in 2011.

But faltering growth and sky-high inflation were just two examples. The UPA-II was spoilt for embarrassments and failures. There were the recurrent instances of corruption and the inability to build consensus among coalition partners, apart from policy blunders such as retrospective taxation, not to mention new legislation such as the national food security act 2013. Basu refers to them at different places and what stands out is the stark contrast between the strident irritation that citizens felt over many of these issues at that time and the apparently amiable discussions that took place in the highest policymaking circles.

What makes this a must-read is the way Basu charges each page with fascinating insights from economics. No issue is spared and the reader is just a phrase away from an example, a game theory or an anecdote from economic history.

The most cathartic and hilarious bits are when Basu shares his boredom as well as amazement at how top bureaucrats and politicians (both in India and abroad) manage to talk without making any sense. In fact, during a discussion on monetary policy in G-20 countries, he “decided to offer a meaningless comment which used the right words and had the right soundbites” but “had no meaning” and then sat back to enjoy people agree and disagree with him.

Basu also peppers interesting incidents from his personal life and doesn’t shy away from sharing the cheeky bits — like when he stole a menu card for a dinner that the PM hosted to honour Venkatraman Ramakrishnan winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry or the time when he almost joked that he always thought Mangalore was a spelling mistake!

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.

Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google

Continue with Google