Mukbang Videos of Seafood Eaten Alive, Tortured Spread on Facebook, YouTube

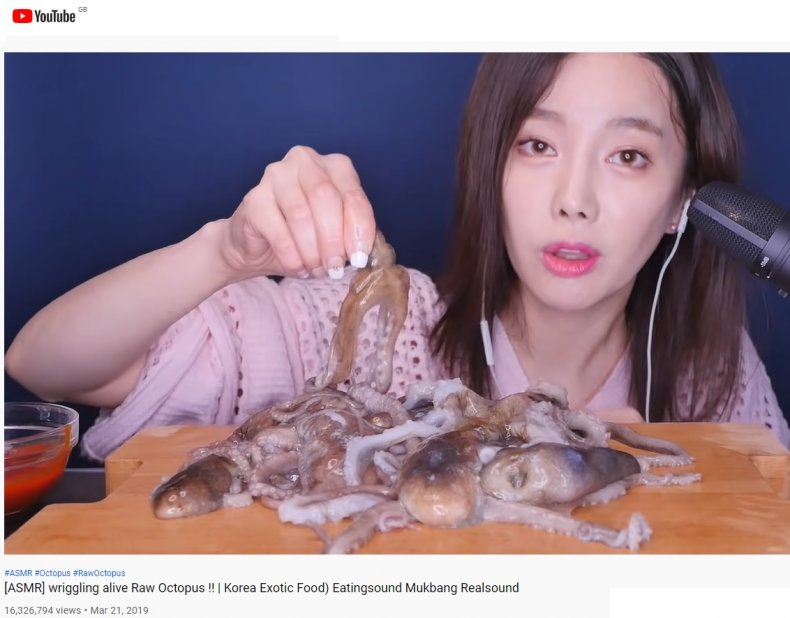

Spread atop a wooden board are about half a dozen small octopuses, alive and squirming. The Korean "mukbang" influencer Ssoyoung warns her viewers not to try the delicacy—a known deadly choking hazard—at home.

Not unlike her peers in the realm of internet eating shows, Ssoyoung had assembled a familiar set-up: Her plat du jour, a condiment on the side, and a professional microphone to amplify the squish and wriggle of every bite.

Ssoyoung grabs an octopus and tightly squeezes its tentacles from top to bottom, close to the microphone, before dipping the live animal in a red sauce and popping its whole, bulbous mantle—which contains its organs—into her mouth.

Distressed, the octopus splays its tentacles all over Ssoyoung's face. She chews and slurps up the mollusk's arms, one of which writhes into her nostril, occasionally giggling at its futile struggle as she prevents runaway octopuses from escaping the board.

The video [warning: graphic content], from March 2019, has generated 16 million views on Ssoyoung's YouTube channel, which boasts more than six million subscribers, at the time of writing.

It prompted widespread criticism from viewers and fellow influencers, who accused Ssoyoung of torturing the animals. Debates also arose over whether social media platforms should enact more stringent policies regarding mukbang content depicting animal cruelty.

Mukbangs have attained a global reach over the past few years, creating a new medium to manifest a universal love for food. First launched in South Korea, the phenomenon's name blends the Korean words for "eating" and "broadcast."

The videos involve people filming themselves enjoying food—either silently or in-between chatter, alone or with company—and posting it online. So-called "mukbangers" craft opulent platters of colorful, textured foods, capturing their meals with state-of-the-art recording equipment.

Many successful mukbangers stimulate their audiences' senses by deploying autonomous sensory meridian response, or ASMR. And in today's influencer economy, mukbang creators are able to profit from every bite and sip by monetizing their videos and securing sponsorships.

But like other internet subcultures, mukbangs—and the platforms that host them—have engendered controversy.

Beyond fads such as eating raw honeycomb and Hot Cheetos-flavored dishes, a highly provocative trend involving cooking or eating marine animals while they're still alive has garnered continuous backlash.

Across mainstream social media platforms, there exist widely-shared videos of people tearing off octopuses' wriggling legs with their teeth, biting through the shells of stressed crablets, smacking water-spraying geoducks, and placing vigorously moving sea creatures onto fired-up pans or grills.

This trend has attracted a polarized viewership, from wide-eyed fans clamoring for more, to revolted critics charging animal cruelty. The outcry has left many wondering how such content is allowed to be disseminated on the biggest social platforms.

Facebook, which also owns Instagram, prohibits content depicting violence against animals unless it occurs in certain contexts, such as food consumption and preparation. Google-owned YouTube's policy on animal suffering similarly makes exceptions for "traditional or standard purposes such as hunting or food preparation."

Mukbangs are inherently culinary in nature, meaning these policies bear cracks that allow content involving live marine animals to slip through, virtually unbridled. As a result, tormenting animals before eating them is a trend that enjoys a seat at the table.

Newsweek has contacted Facebook for comment.

Upon reviewing examples of mukbang videos involving live animals sent by Newsweek, YouTube spokesperson Ivy Choi said: "YouTube has never allowed content that's violent or abusive toward animals. Our Community Guidelines are designed to account for cultural differences when it comes to consuming animals, and the videos shared with us by Newsweek do not violate our policies."

Mukbangers vs. Animals

Ssoyoung is infamous for having tapped into the craze. While her 2019 octopus video was certainly her most controversial post, it wasn't a one-off.

The influencer's content employs a formula that involves preparing visibly distressed sea creatures for consumption, sometimes eating them alive. Despite creating content with live marine animals for several years, Ssoyoung handles them with excessive horror, revulsion and clumsiness.

She jumps and shrieks with laughter when squids spray water as she slices their mantles off, or when shrimp spring out of an overcrowded dish as she prepares to break their shells. She wails in disgust while holding gigantic still-breathing fish or octopuses before cooking them, and has wrestled with a large drum fish on the floor. In one video, she attempts to knock out a flailing striped beakfish by striking it with the back of a knife.

In another, Ssoyoung grabs a houndshark out of a tank with little water, only to drop it on the floor. As the panicked animal helplessly flounders on the ground, Ssoyoung acts terrified, falling down to the floor and backing away while screaming.

The influencer included this segment in a Facebook video titled "Ssoyoung vs. Food," a compilation of her misadventures in handling scared sea creatures.

On YouTube, some of Ssoyoung's videos are only available to users who are signed in and of age, with the added barrier of a content warning message and a button they must press to proceed.

Instagram has blurred 10 of the mukbanger's posts, along with a similar warning indicating potential "graphic or violent content" and a go-ahead button. Her Facebook content is unrestricted.

Newsweek has reached out to Ssoyoung for comment.

Borami Seo, Korea executive director at Humane Society International (HSI), an animal rights nonprofit, told Newsweek mukbang held a simpler meaning prior to its social media boom, having been used by Koreans to describe meals shared between family and friends.

"We see mukbang in situations where we enjoy eating food. But these days, the whole point of mukbang became more like making eating food like an activity for public display," Seo said.

"So the emergence of eating live animals is really about doing something so outrageous that you get more viewers. It's like provoking viewers to respond to that, so the more plays, the more profit."

Following widespread accusations of animal abuse and torture, a spokesperson for Ssoyoung told Insider in April 2020: "Ssoyoung channel's primary goal and intention is to introduce various kinds of food and to deliver joy to our beloved viewers across the world. As Ssoyoung is a Korean YouTuber, we put our basis on Korean food culture."

The representative went on to say the influencer acknowledged her content "may have caused some viewers to feel uncomfortable," but she "never had or will have any [intentions] of purposely abusing or torturing live animals under any circumstances."

The consumption of live marine animals is not foreign to South Korea, where small live octopuses are served as delicacies—named sannakji—in fish markets and restaurants. However, Seo believes any defenses citing cultural customs are moot because the practice itself merits reflection and debate.

"When you bring out your own culture defense, other people will back off and be wary of what they are going to comment on that," she told Newsweek.

"Eating live marine animals is widespread in Korea, [...] but I wouldn't call this Korean culture, because I believe culture is something that you want to respect and you respect and believe in values and customs that reflect Korean society.

"I think it's important to acknowledge that cultural customs change, it's not static, it changes and reflects the modern times that we live in. So not just from mukbang, not just for [Ssoyoung's] content, but eating live seafood in general needs some more society discussion, I think, in Korea."

Local Customs or Internet Culture?

The role culture plays in debates over live seafood mukbangs is not insignificant. The most prominent mukbang creators who feature live animals in their content are from east Asian countries, such as South Korea, China and Vietnam.

Backlash against the content has also included an onslaught of racist abuse towards the influencers, peddling the very rhetoric that fomented hate speech and violence towards Asian people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Amid the swirling anti-Asian narratives, racist scrutiny towards Chinese food culture has emerged from the claims that the country's wet markets helped the coronavirus transfer from animals to humans.

Chinese social media was not exempt from the mukbang takeover. Much of Chinese users' mukbang content is posted on video-sharing apps Douyin—China's version of TikTok—and its competitor Kwai. Seafood dishes slathered in sauce and seasoning are particular favorites among the country's influencers.

However, some mukbangers have taken it a step further, filming themselves cooking live sea animals prior to consumption, or outright eating them while they're still kicking.

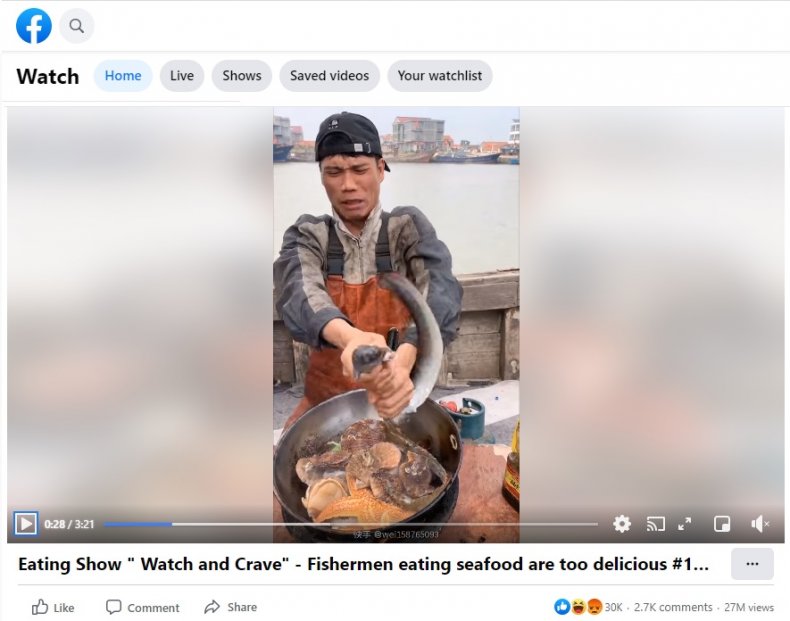

A subset of comedic mukbang videos has made internet stars of Chinese fishermen who, while docked at ports, are filmed cooking medleys of freshly caught marine animals, then eating the resulting dish. One popular creator, a fisherman named Haitou Hantou, has upwards of 4.9 million on Kwai and 4.2 million followers on Douyin.

In many of his videos, Hantou begins by placing vegetables in an oiled wok. The searing heat of the pan is apparent from vegetables crackling on contact, intense oil splatter, and the fisherman leaning back while making pained faces.

After throwing multiple live marine animals—such as fish, octopuses, lobsters, crabs, starfish, and clams—into the wok, Hantou sautées and coats them in various sauces. The fisherman savors his meals in separate videos.

When dumped into the pan, the animals can be seen writhing, with some creatures attempting to escape the pile. For Hantou, the latter present a comedic opportunity in trying to contain them.

In several videos, Hantou struggles with eels slithering chaotically out of the scorching wok. While yelling in apparent panic, the fisherman frantically attempts to return the scared animal in the pan and slam a lid on it.

The eels end up killed off-camera, as following videos show Hantou presenting their gutted bodies before cooking them.

Newsweek has contacted Hantou for comment.

Facebook, Instagram and YouTube are blocked in China. However, Chinese creators' videos have permeated to the platforms, by way of pages and channels dedicated solely to sharing various mukbang videos.

Mukbangs posted by gourmand fishermen can be found spliced together and re-uploaded on Facebook and YouTube. Hantou's YouTube channel has around 2,410 subscribers.

Footage of Chinese social media users eating live sea creatures, primarily sourced from Kwai, have proliferated on mainstream social media outlets via continuous re-posting.

In the videos, influencers eat from plates containing moving animals such as octopuses, small crabs, shrimp and geoducks. Prior to consumption, the mukbangers season the animals with soy sauce, chili flakes, and various other condiments.

Dr. Peter Li, China policy specialist at HSI, said there is "no cultural precedent" to the consumption of live animals in China, which would mean such content is purely entertainment-focused and leads to unnecessary animal suffering.

"Compared with the rest of the world, the Chinese eat very little, almost nothing raw," he told Newsweek. "Because there is a bad lesson the Chinese collectively learned because of disease—if you eat anything raw in China in ancient times, you're going to die."

The controversial mukbang videos could not only enable young audiences to "lose sympathy for animals," Li said, but also serve distorted narratives that antagonize Chinese people.

"For the Chinese themselves, if they do this in Chinese social media and it gets viewed outside China, [...] you are helping perpetuate the falsehood about your culture," Li said. "And for people outside China, when they see that, the misperception of Chinese culture—of Chinese people having a propensity to animal cruelty, the eating habits are backwards, uncivilized—they get reinforced."

Dr. Evan Sun, wildlife campaign manager at World Animal Protection, a nonprofit, told Newsweek that filming and viewing the controversial mukbangs "should not be accepted and encouraged."

He added that such content could enable food waste, as well as risks to public health posed by the consumption of live marine animals, such as zoonotic diseases and parasitic infections.

"The animals in these videos are clearly subject to suffering, purely for entertainment, and it is worrying that policies like this allow for these cruel consumption practices to become mainstream," Sun said.

"Social media platforms must act quickly to review and remove videos that depict this type of animal abuse. The longer these videos stay online, the more people view them, the greater risk they will spawn copycats elsewhere."

Mukbang videos are already on Chinese authorities' radar. In August 2020, President Xi Jinping boosted the country's "Clean Plate Campaign" to reduce food waste amid the pandemic. Days after the announcement, state broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) published a piece critical of mukbangers, accusing them of views-driven binge eating, as well as promoting food waste and unhealthy eating habits.

Beyond advocates for animal welfare, mukbangs that feature live animals have also perplexed some experts in Asian gastronomy. Food writer Corinne Trang, who has authored multiple cookbooks on Asian cuisine, believes such content to be "barbaric," with its creators showing disrespect towards their countries' culinary customs.

"If you really look into these different food cultures, they take such pride in the way food is prepared, in the way food is served, in the way they share food," she told Newsweek.

"These are old, traditional food cultures, and then you have these youngsters who want to reel in as many followers and they're going 'Oh, let's up the ante.'

"I've traveled all over, I've written eight books on Asian food cultures—not once have I seen this kind of behavior in Asia. Ever."

Trang specified that while there is no difference between the mukbang videos and instances of animals being cooked or consumed alive in other settings—be it lobsters boiled alive in restaurants or oysters eaten off the shell—there is a contrast in tone.

"In terms of shock factor, in one it doesn't exist, in the other that's all it's about," said Trang.

"It's not even about eating. It's not even food in the way food is supposed to make you feel as a person, which is usually comforting and satisfying. It's pure shock. It's pure entertainment."

While unfamiliar with the polarizing mukbang videos, Christine Ha—third season winner of competitive cooking show MasterChef and executive chef of Houston-based Vietnamese gastropub The Blind Goat—believes any cooking process involving animals should ensure minimal suffering.

"I think you really have to respect what you're eating and what the earth has given you," she told Newsweek. "So that goes from how you decide to butcher the animal or how you decide to kill the animal, that's why I believe it should be a quick kill."

Ha said there is a "fine line to tread" between educational content on cultural food customs versus exploitation of animals for social media clout.

"I think you can have a camera and take it to a seafood market and show, 'Oh, here are the different kinds of seafood you can get at a Vietnamese market, I'm going to choose clams and this fish today, and then let's show them how they prepare it after you pick it out, and then what does it taste like'—that's one thing," she said

"I feel like the person making the video will know in their gut which way they're going. And I think if you're doing a video where you're just trying to make it very extreme [...], you know when you're exploiting the animal for your own benefit."

The Science Behind Marine Animal Suffering

Concerns over pain experienced by marine animals in mukbangs have been a major point of contention, especially as the consumption of live octopuses pierces into mainstream content.

In a now-deleted video, hugely popular Canada-based mukbang influencer SAS ASMR, who boasts 9.21 million YouTube subscribers, ate a small live octopus during a visit to her home country Thailand.

Vietnamese mukbanger LINH-ASMR counts live octopus feasts among her most popular and highly-requested mukbangs, racking up hundreds of thousands of views on Instagram clips of her YouTube videos, which attract views in the tens of millions.

Unlike her counterparts in other countries, LINH-ASMR's videos do not feature theatrical performances. She instead makes use of ASMR to create tingling experiences for viewers while chewing on octopuses' curling tentacles, at times accompanied with other audibly textured foods.

When seasoning the octopuses, LINH-ASMR has squeezed lime or lemon juice, poured spicy sauce, or dipped them in soy sauce—all of which have elicited reactions from the mollusks. When octopuses have attempted to scurry away in some videos, the influencer could be seen promptly grabbing and returning them to the platter.

Following heavy criticism, the influencer added disclaimers to her live octopus videos, urging people to avoid watching if they are offended by the dish (which she has dubbed as "exotic food" from Korea.) Instagram has restricted some of her content with blurs and warnings, whereas YouTube—where she receives most of her views—has not.

Newsweek has contacted LINH-ASMR for comment.

Dr. Robyn Crook, assistant professor of biology at San Francisco State University, spearheads the Crook Lab, which researches injury-induced behaviors in cephalopod mollusks, such as octopuses and squids.

Crook said cephalopods differ from other mollusks in that their nociceptors, or pain receptors, respond strongly to a number of stimuli. They also exhibit complex behaviors following an injury, such as grooming and concealing wounds, heightened defensive and startle responses, as well as avoidance of settings linked to painful experiences.

Crook told Newsweek mukbang videos in which live cephalopods are dismembered are very likely to cause them pain.

"We know from experimental work on octopus welfare that being bitten would likely be perceived as painful," she said. "Not to mention the extreme stress of being removed from water and handled."

Referring to a video in which Ssoyoung helps a fish market worker invert a large octopus' mantle to remove its viscera, Crook said the process probably resulted in a "very slow death with significant tissue trauma."

Based on a study conducted by her lab, Crook said acids such as lemon and lime juice would be "exceptionally painful" to octopuses with skin damaged from being fished, held in close proximity to other octopuses, then handled roughly. Salt and soy sauce would similarly cause a great deal of pain on abraded skin, a reaction Crook said is akin to rubbing salt into a wound.

Due to its high level of sodium, soy sauce in particular strongly activates cephalopods' neurons and muscles, leading to the "dancing squid effect," which sees the mollusks moving their tentacles even soon after death.

As cephalopods lack thermal nociceptors, Crook said boiling and cooking them in hot oil may be less likely to cause them pain. This could also result in a lack of aversive response to capsaicin, the active ingredient in chili peppers, though this has not been tested experimentally.

On the other hand, bivalves, which include geoducks, mussels, and oysters—the last eaten live and considered a delicacy by many westerners—are unlikely to experience pain due to their "very simple" nervous systems with "little centralization."

While gastropods—such as abalones, which were consumed in some mukbangs—have a more complex nervous system and a wider array of responses to noxious stimuli, there is no clear-cut evidence as to whether they are aware of a sensation like pain.

Robert Elwood, emeritus professor at Queen's University Belfast's School of Biological Sciences, has researched the pain capabilities of decapod crustaceans, which include lobsters, crabs, and shrimp.

While scientists can't measure pain in animals, he said, there are ways to prove whether they exhibit awareness-based behaviors rather than simple reflexes. Studies conducted on decapods found their behavior to be "consistent with the idea of pain."

"They showed very rapid avoidance learning towards noxious stimuli, they show prolonged rubbing of a wound or guarding of a wound," he said.

"Animals who have been subject to electric shock show signs of anxiety, there are long-term changes in behavior and they will give up very valuable resources to escape the noxious stimuli and they show physiological stress responses."

Dismemberment of the animals, whether by pulling their claws off or taking bites out of them, is highly likely to cause pain, Elwood said. His research has found crustaceans do not respond to capsaicin, though acids such as lemon juice are "highly aversive."

Depending on the crustacean's size, dropping it into boiling water might hurt it for a couple of minutes or less. As for heated pans, decapods' vigorous escape attempts indicate a good chance that they are sensing pain.

In many mukbang videos, lobsters and shrimp can be seen flicking their tails repeatedly, a mechanism that has resulted in shrimp ejecting themselves from influencers' pans and plates. Elwood said this is an escape response typically used underwater.

"When they flick their tail, the tail is out straight, and they flick it under the body, which would normally make them jerk backwards, away from what's affecting the head end," he said. "And that's what they're doing in those [mukbang] environments, they're doing what they would normally be doing to escape."

From an animal welfare perspective, Elwood said the humane way to consume crustaceans is by killing them quickly beforehand. "You wouldn't hack the leg off a live sheep and then cook that," he said.

"We can't prove that a sheep feels pain, but we accept it's so likely that they experience pain that we must give them some protection, that we can give them the benefit of the doubt—what we call in science the precautionary principle.

"We take precautions, and even though you can't prove something outright, you still take precautions to maintain the animal's welfare."

The U.K. parliament is debating a landmark bill that would consider invertebrate animals such as octopuses, squid, lobsters, and crabs as sentient beings. Amendments to the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill would mandate more humane ways of killing them and possibly ban practices like plunging lobsters in pots of boiling hot water.

'Huge Stigma'

Despite widespread condemnation, however, not much has been done to address mukbang videos involving live sea animals.

While stricter regulation on social media platforms would be a start, the content continues to flow freely, promoting methods that torment the animals and providing fodder for hate speech towards Asian people and cultures.

Ha said that while racism is never warranted, such controversial content can play into existing inclinations to paint Asian cultures with the same brush. "I'm not gonna say I'm better than someone else who [eats live marine animals]," Ha told Newsweek.

"But I do agree that there is a huge stigma now, especially after COVID-19 and people believing that it came from the wet market or whatever, I think it has kind of blanketed Asian cuisine as a whole.

"I feel like, perhaps, yes, with these videos, there might be generalizations made. Like, 'Oh, because this person in South Korea is eating this, this must mean that every person that looks similar to them, [...] they must all be eating the same things.'

"It's a slippery slope and it's a dangerous slope to go down, too. Once you start generalizing a mass of people, I think it becomes dangerous in all sorts of ways, not just food."