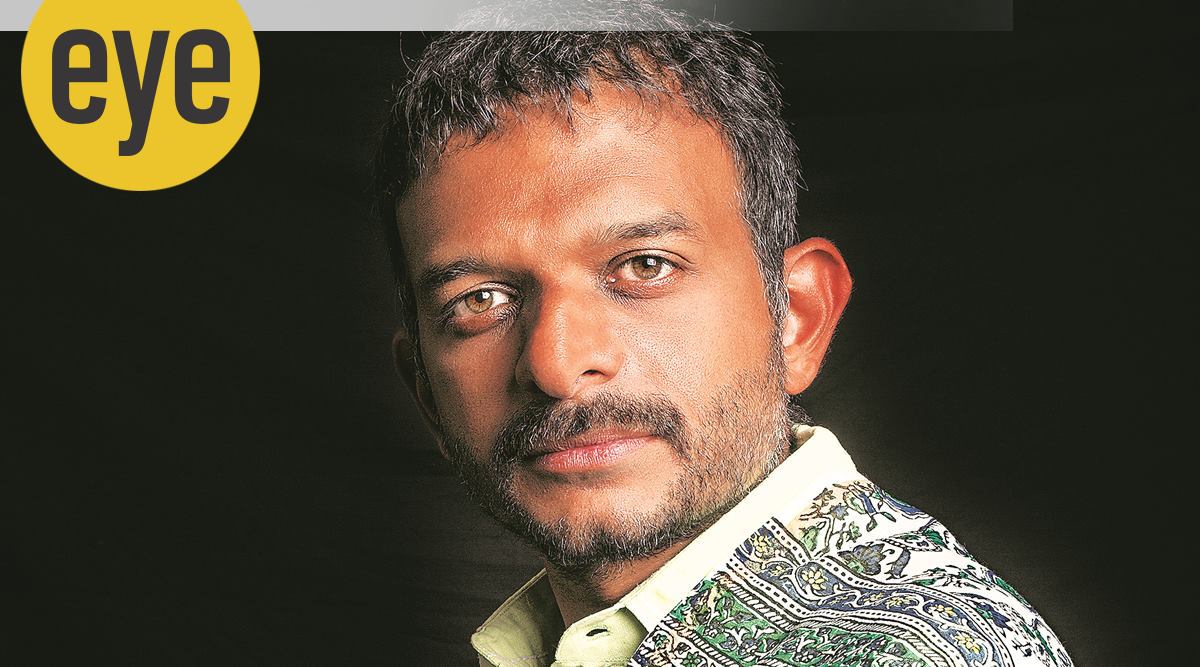

Taking Notes: Carnatic musician-activist TM Krishna. (Photo: J Keshav Ram)

Taking Notes: Carnatic musician-activist TM Krishna. (Photo: J Keshav Ram) What made you relook into your past writings in your new book of essays, The Spirit of Enquiry: Notes of Dissent (Penguin Random House, Rs 599)?

When I looked back, I noticed subtle differences even between the pieces. You usually don’t revisit what you write or stop to see if there’s been an evolution in your thought process. This book helped me understand that. Rethinking the past is lacking today because nobody wants to be seen in the wrong. People define wrong and right and want the politically acceptable position; none is willing to live with the fluidity. The only things consistent are honesty, integrity and ethical living. Everything else is fundamentally fluid. People confuse a change in thinking with hypocrisy, which is a result of dishonesty and entirely different from being willing to respond to new ideas and reflections. The book has creases, greys and contradictions.

Why did you respond to an old column — your letter to the Muslims of India?

It’s probably one of the worst pieces I’ve written. There was no serious engagement with the Muslim community when I wrote it. That is fundamentally wrong. Later, a friend of mine arranged a meeting with people of different social strata from the Islamic faith. After many discussions, I’ve learnt that good intentions are not good enough to have an opinion. My good intention never looked at the nuance of what it means to be this person and to be put through ridiculous scrutiny on a daily basis. I was entirely wrong and, hence, I have responded to it.

Your essay ‘Boycotts And Bans Are Not Enough, We Must Problematise The Work Of Artists Who Disturb Us’ talks of artistes and their art. Can the two be separate?

We tend to have two extreme positions. One is that artistes and art are entirely separate. So, I don’t care what kind of person the artiste is. The other, they’re not at all separate, so, throw the art of this horrible person into the dustbin. Both positions allow escape routes and don’t actually grapple with the contradiction. Say, you listen to the music of a person who has violent thoughts, believes in White supremacy or is controversial like (the German composer Richard) Wagner, what do you do with that music? Listen to the music is what I’m saying. Is the music beautiful? Are you horrified by it? Allowing that conflict, the ugliness to be alive along with the reality that the same person made this (art), such complicated memories are important for society to not forget the messiness of it. We want a certain absolutism, but there can’t be a clean solution.

You are often told to sing and to not talk politics. Why do an artiste’s political views disturb the audience?

The world we address — middle class, upper-middle class and the socially privileged — including artistes, say politics is gandagi (filth), don’t talk about it, just sing, dance, play the flute, write poetry. They don’t realise the politics of reality. But the artistes and communities that have remained marginal, their art has always been overtly political, because they have no choice. They have to tell you about the horrors of their life, be it rap or hip-hop. Some now say, you can be political the way I think you should be. If I say ‘yes, the temple in Ayodhya should be built’, they are happy.

The book cover

The book cover

Many have refused to listen to my music. They believe I’m a traitor of culture, as an insider, as an upper-caste male practising an art form that comes with much-believed historicity and antiquity. But, on the flip side, many who’d never heard my music are listening to it, based on something I wrote. Many are listening to Carnatic music. When you challenge powerful ideologies, call out an oppressive structure, it will be uncomfortable. I’ll practise, but I’ll question and create a conversation.

So, why did you pull back from speaking about Dalit politics?

I’ll never have the lived experience of a woman, a trans person, or a Dalit. I’m what you call an ally. The truth is, none of us actually know where the line is, when you are crossing it. The line can be different at different times, and we need to be respectful of it. I’m very clear that I’m not speaking for anybody. I’m speaking for myself, from a position of privilege to the privileged, about my understanding of what we carry as privilege. You could think I’m taking up space, that a Dalit person should speak rather than me. I welcome the criticism from the Dalit communities. I need that check, to be told, this is not your business, keep quiet. I pause and step back. It’s constant learning.

What are your thoughts on the cultural changes in ‘classical’ music?

Any kind of cultural change happens in a soft manner. You don’t notice it for a long time. It’s very complicated and layered. Among the younger generation, there’s far more recognition about the issues I raise. They engage robustly. They don’t need to agree with everything I say but that it’s generated this amount of interest to learn is refreshing and wonderful. Tags of classical and folk will slowly dissolve because of greater aesthetic experiences. Bluntly speaking, I don’t expect my generation to really change.

You recently moved the Madras High Court challenging the new IT rules.

I believe these rules have issues with freedom of expression and privacy. I’m challenging them as a creative private citizen. We are waiting for the government to respond.

Your next book looks at India through five symbols?

I’ve chosen the Preamble, emblem, flag, anthem, and motto — that have come to symbolise India. By eulogising them or considering them archaic, one isn’t engaging with them. The book, a critical hypothesis, will investigate them in today’s context and imagination.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.

Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google

Continue with Google