June 27, 2021 6:35:27 am

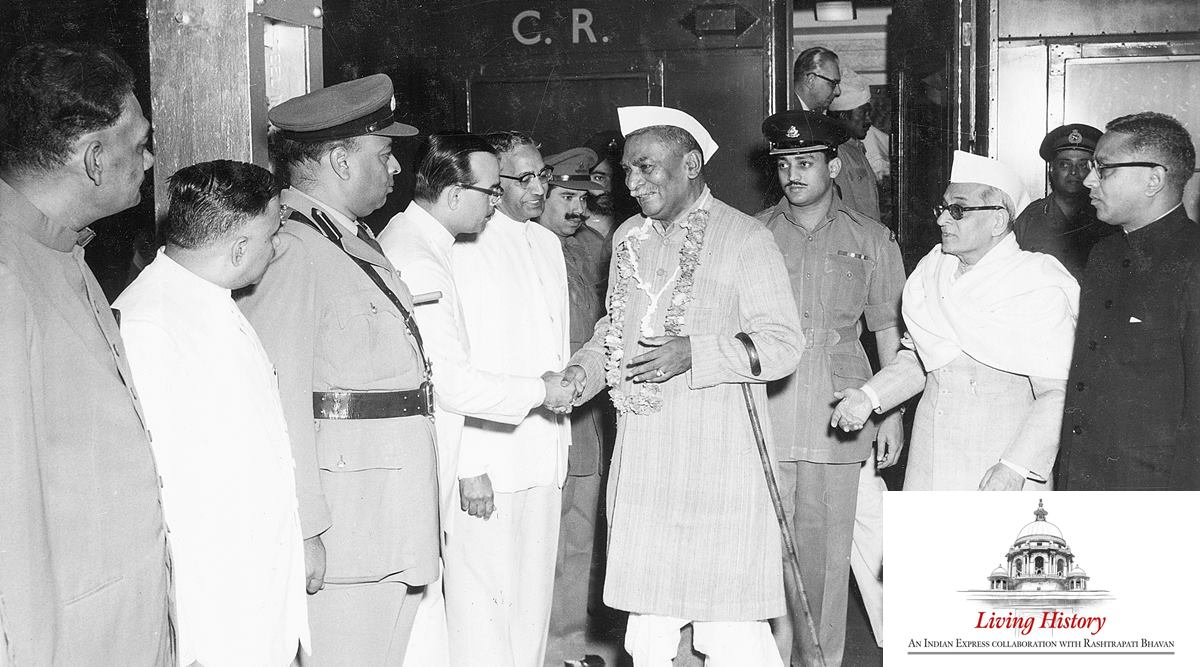

Officials receiving Rajendra Prasad at Haridwar station. (Rashtrapati Bhavan photo archives)

Officials receiving Rajendra Prasad at Haridwar station. (Rashtrapati Bhavan photo archives) By Praveen Siddharth

Ensconced in the hot and humid confines of the government house at Calcutta, British governor-generals were often desperate to get away to some place cooler. The idea of a “retreat” was born — from the heat, the dust and grind of daily work. In 1801, colonial administrator Richard Colley Wellesley, first Marquess Wellesley, took over a country house along the Hooghly in Barrackpore and made it a weekend home. He tried to connect the government house in Calcutta with this new bungalow through a straight road. But when the East India Company declined to give him funds, he proceeded to travel during the weekends in a grand barge along with his entourage in a flotilla of ships!

Another practice that soon developed among the early governor-generals was called “the march”. Governor-generals with their retinue would undertake long journeys to acquaint themselves with the lay of the land and impress upon the people the might of the British empire. These marches were lavish affairs, as novelist Emily Eden writes in her journal on November 30, 1837. “This morning we are on the opposite bank of the river to Allahabad, almost a mile from it. It will take three days for the whole camp to pass. Most of the horses and the body-guard are gone to-day, and have got safely over. The elephants swim for themselves, but all the camels, which amount now to about 850, have to be passed in boats: there are hundreds of horses and bullocks, and 12,000 people.” Eden was narrating a journey up-country, done over 18 months, by Lord Auckland, from Calcutta to Shimla to Lahore.

Such days of travel were often filled with unseen dangers. In October 1862, Lady Canning, the immensely popular wife of Earl Canning, the first viceroy of India, while on retreat to Darjeeling caught malaria and died. The residents of Kolkota still relish a sweet dish ledikeni, which was named after her. In 1872, Lord Mayo on a visit to the Andamans was assassinated by Sher Ali Afridi. He remains the only viceroy to have been assassinated. In 1873, a newly discovered butterfly species in the Andamans was named after him — Papilio Mayo. In 1863, viceroy Elgin died of more natural causes, from a heart attack. What was not natural however, was that at that moment he was attempting to cross a wildly-swinging rope and wood bridge over the river Chadly, in Kullu.

Lord William Amherst was the first governor-general in 1829 to go to Shimla while on march in north India. This practice became an annual custom, which began with viceroy John Lawrence in 1864 and continued all the way until 1947. Along with the viceroy, the entire government would move to Shimla from April to October each year. For almost a century, when the British empire in Asia stretched from Mesopotamia to Burma, a fifth of mankind came to be governed from Shimla.

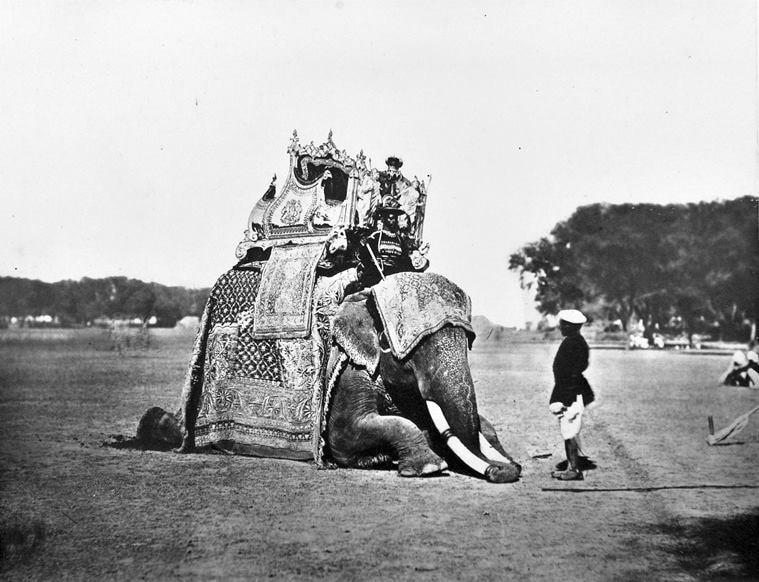

The Viceroy’s elephant. (Rashtrapati Bhavan photo archives)

The Viceroy’s elephant. (Rashtrapati Bhavan photo archives)

During these times, the most appropriate form of transport for the viceroy was unquestioningly the elephant. In 1852, the hathikhana of the governor-general consisted of 146 elephants. Lord Dalhousie had a silver howdah made, which he used when he met Raja Ghulab Singh of Jammu at Wazirabad in December 1850. This silver howdah became one of the most prized possessions of future viceroys, but they soon faced an embarrassing problem. They had no suitable elephants to straddle the howdah on! By 1888, in Lord Lansdowne’s time only three elephants survived. When the Earl of Elgin arrived in 1895, only one elephant survived.

Since the silver howdah had come to symbolise the power and prestige of the viceroys, a solution had to be found. The Maharaja of Benares stepped in by lending his gigantic state tusker. This was the mount that both Lord Lytton rode during the Imperial Assemblage in 1877, as well as Lord Curzon during the Delhi Durbar in 1903. A sweet irony that the heights of British supremacy were proclaimed from on top of a tusker that belonged to an Indian ruler!

The elephant would steal the show during these durbars. As The Illustrated London News recorded on January 27, 1877, the tusker seemed “to have a fair idea of his own importance. Instead of walking on quietly and steadily as a well-conducted elephant should, he would insist upon stopping every now and then and taking a look around. Nor could anyone persuade him to move until he had satisfied his curiosity. The result was that every few minutes the ‘halt’ had to be sounded, so as to preserve the line of procession unbroken.” Unsurprisingly, there were no elephants in procession in the durbar of 1911.

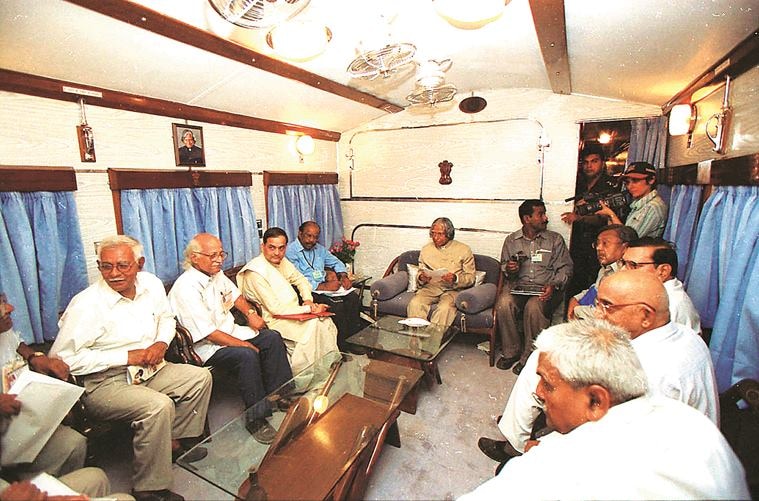

APJ Abdul Kalam on a train from Harnaut, Bihar. (Rashtrapati Bhavan photo archives)

APJ Abdul Kalam on a train from Harnaut, Bihar. (Rashtrapati Bhavan photo archives)

To the British, how they travelled mattered immensely since they had to show that they were the masters. On the other hand, after Independence, the concern of our presidents has been to connect with the people. Nevertheless, certain traditional modes of travel persisted. The gold-plated unique six-horse-drawn buggy was used intermittently, until as recently as 2017, by our presidents during ceremonial occasions. Today, this buggy rests in the Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum, New Delhi.

Another tradition that has continued, albeit with an entirely different purpose, is that of the “retreat”. The President has two retreats now, one in Shimla and one in Hyderabad. The decision to establish a retreat at Hyderabad was taken by Rajendra Prasad in 1956 to ensure that the office of the President is not perceived as belonging to just one part of the country alone.

This week, President Ram Nath Kovind travelled by train during his maiden visit to his village near Kanpur. Stopping at railway stations close to his village, the journey allowed the President to interact with the residents in a manner air travel would never have allowed.

Another president who had travelled by train in recent times was Dr APJ Abdul Kalam in 2006, from Delhi to Dehradun.

We have come a long way from the days of travel by extravagant steamers and unyielding pachyderms. And, like all journeys, we will do well to remember that it is not our destination that really mattered, but how we got here. Somewhere along this journey from viceroys to presidents, our nation was born.

(Praveen Siddharth is private secretary to the President of India)

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.

Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google

Continue with Google