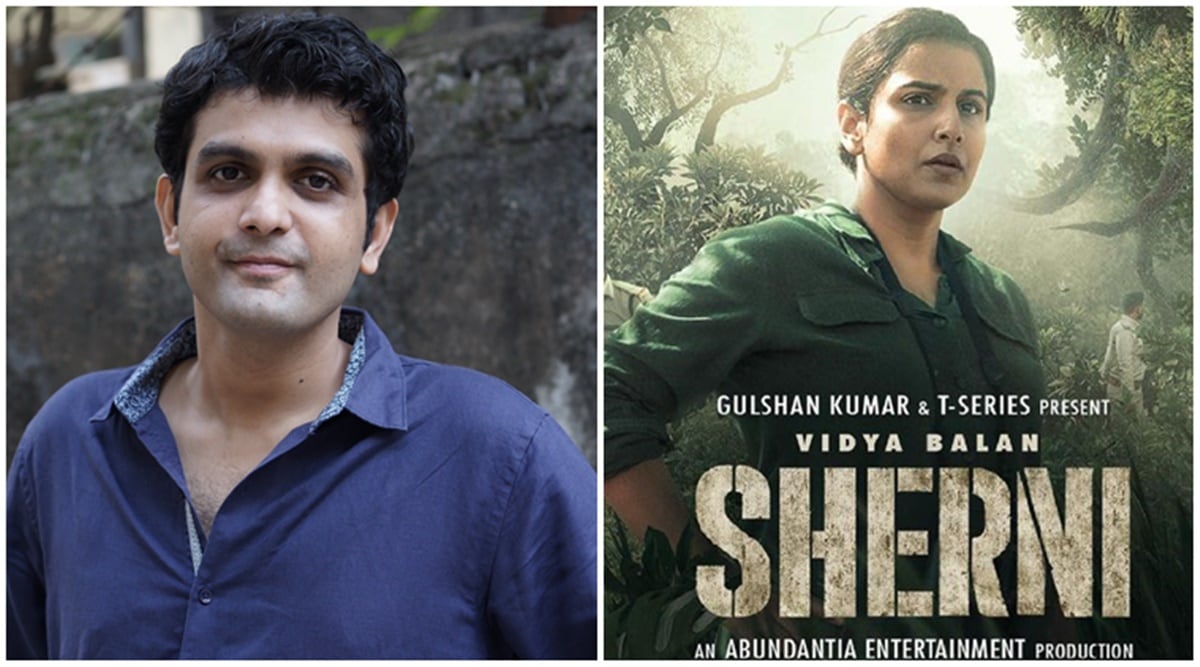

Director Amit Masurkar speaks about the making of Vidya Balan-starrer Sherni. (Photo: Aditya Naik, Vidya Balan/Instagram)

Director Amit Masurkar speaks about the making of Vidya Balan-starrer Sherni. (Photo: Aditya Naik, Vidya Balan/Instagram) Amit Masurkar is a man who works at his own pace, much like his films. A four-year gap between Newton and the latest, Sherni, might seem a lot to many, but the director is unfazed. He says, “It’s not deliberate.” The same can be said about the thought-provoking Vidya Balan-starrer, which seems to reflect the director’s own calm.

In an interview with indianexpress.com, Masurkar deconstructs the unhurried pace of Sherni, the brief he gave to Vidya Balan and why letting go of the “colonial” gaze is essential to telling a jungle film.

Many in the audience feel Sherni is perhaps the most full-fledged jungle film that Hindi cinema has seen in years. How does this response make you feel? Were you anticipating it?

We believed that people deserved a good jungle film, a good film about conservation because it is the need of the hour. You need a story like this to come out in Hindi cinema. It may sound a little audacious but we were expecting the conservation community to support it and also for the common people to like it. This affects us, the human beings, and it’s about our future as a species. So, it is something I believe should be watched.

It took you four years to bring your next after Newton, which was a huge success. Didn’t people tell you to work faster so as to cash in on the popularity that you received from Newton? How did these four years pan out?

It seems like a long time, but actually 2019 is when Aastha Tiku (story, screenplay) started writing Sherni. We were supposed to start in December 2019 and release it in 2020 but it takes time to write something like this, and then the pandemic happened. Hence the delay. Otherwise, the time gap was just organic. It wasn’t deliberate.

View this post on Instagram

What was it about Aastha’s story that made you feel it needed to be told?

It was the core philosophy that humans are a part of nature, not separate. Conservation is not a hero-driven process but it is something that requires an entire community to come together and put in a lot of effort and also share knowledge in order to get things done. And this has to be continuous.

The reason we chose the tiger is because it is at the top of the food chain in the jungle. To save the tiger, you end up saving the entire jungle and with that the entire ecosystem. All these factors contributed in me getting interested in the subject.

Also, the characters that Aastha came up with were pretty interesting. she doesn’t come from a typical film background, the characters were more real and they were coming from a space of research and personal experiences. So, I was attracted to not just the philosophy but also the way the story world was built.

It’s interesting how the idea of people coming together for a cause reflected in Newton as well. So was the concept of an sincere government officer trying to do their job without any heroism attached to them. And of course that both Sherni and Newton have jungle as the backdrop. Do you feel passionately for these aspects that they recur in your films?

Newton was a very different story. I had written it with Mayank Tewari and the basic theme was about democracy and about this one person, who was on a quixotic journey and was a very Donkeyote (2017 Spanish documentary film) prototype. It was a very different world and could have been set in various locations.

We chose to set it in the jungle because it was a very powerful visual of someone carrying an EVM machine in the middle of a jungle to conduct elections. But Sherni had to be set in the jungle because it was about the jungle and the forest plays an important character in the film.

How is Sherni so quiet? It seemed you relied on the atmospheric sound of the jungle to tell the story. Is it because the story itself is thrilling that it doesn’t need an external design to amplify its effect?

If you look at other jungle films, there’s a very colonial way of looking at it. Forest is a deep, dark, mysterious, dangerous place, full of unknown spirits and animals and they are wild and can attack you any time. So, you go in slowly, you creep into the jungle and somebody is watching you and you have that sound design around it.

Sherni director Amit Masurkar seen with DOP Rakesh Haridas and writer Aastha Tiku. (Photo: Aditya Naik)

Sherni director Amit Masurkar seen with DOP Rakesh Haridas and writer Aastha Tiku. (Photo: Aditya Naik)

So, our conscious effort since the beginning was not to look at the jungle with this lens. We wanted to look at it with a very native lens. In Indian culture and mythology, we don’t look at the jungle as something dangerous but as mother nature. We wanted to show it as an open, accepting, warm place. The gaze was very different and our DOP (Director of Photography) Rakesh Haridas is a nature lover and he grew up near jungle areas. So, when we collaborated, we were very conscious that we didn’t want to show it from a very orientalist perspective.

Now, when you talk about treatment, you also think about the background score. There were discussions that we were not going to use typical jungle sound production. There’s a certain sound that comes to your mind when you think about the jungle so we didn’t want to do that.

We also didn’t want to judge because background score can judge a character, their intentions and make them look scary. So, we had to work really hard on the background score to make sure we didn’t get this kind of effect.

View this post on Instagram

Similarly, we had to make sure of this at the editing stage. Dipika Kalra, our editor, had to cut the film in a way where the cuts are not sharp and you should not feel it’s piercing through. It had to have a certain pace, which is the pace of the jungle. When you go in a jungle, you walk for days and you don’t see a pug mark. So, that’s what we wanted to show through the film that it takes time. It’s very easy for someone to say catch the tiger. But how do you catch the tiger?

You hear a line in the film where the guard says, “You go in the jungle 100 times, you may see the tiger once but the tiger sees you 99 times.” It’s also the line that you can use to justify the way we shot and edited the film.

Your characters have agency and need not to be saved by others. For instance, the confident and fearless Jyoti (played by Sampa Mandal). Is it also the reason why you cast people from the village and the jungle area in specific roles?

Yes, it was a conscious choice because we wanted authenticity because everybody is talking in their own accent. Everybody is playing role that they play in real life. 99 percent of the forest guards in the film were actual guards. Most of the forest office staff you see are local people from the Balaghat town (Madhya Pradesh). Romil and Tejas, our casting directors, worked really hard to cast these people.

One of the most powerful aspects about Sherni is how it draws a parallel between the man vs nature debate and the fight between women and patriarchy. And in both her battles, Vidya is leading from the front but without drawing any attention to herself. How was the character conceived and what was the brief given to Vidya Balan?

Aastha met a lot of forest officers during her research, and she felt that that a lot of these female forest officers were actually people, who were there because they loved jungle. They were genuinely interested in it. Many people we met were not very aggressive but they were still very much in charge.

View this post on Instagram

They were people, who liked to learn and enable others. So, these were some of the qualities that Aastha wanted in the character and this was the exact brief that we gave to Vidya.

We told her she is a listener. She is someone, who learns from others. She is not someone, who keeps ordering people around but she leads from the front. That’s how she gets work done.

Even the climax justifies her unassuming nature, where she has blended herself in her new role and is going about her job with the same sincerity. But its mundaneness is surprising for a climax. What did you want to convey through this scene?

Initially, this scene was not in the script. After the pandemic happened and we were all at our homes and nobody knew what was happening with the world. That’s when Aastha though that the film should have a bigger meaning, with what is happening around us. It should be about the theme of the film. It should be something like a wake up call.

View this post on Instagram

This museum that you are talking about is the taxidermy department of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Vastu Sangrahalya (Museum). We have seen it before and we thought what if we set the last scene here and you see Vidya is doing her job as usual but then all the animals that you see in the jungle are taxidermied and they are staring at the camera. When everyone heard about this, they were like this is the only way you can end this story. It needs to hit you and be powerful.

And again it’s not just the idea and the visuals but also the background score. It really hits you.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.