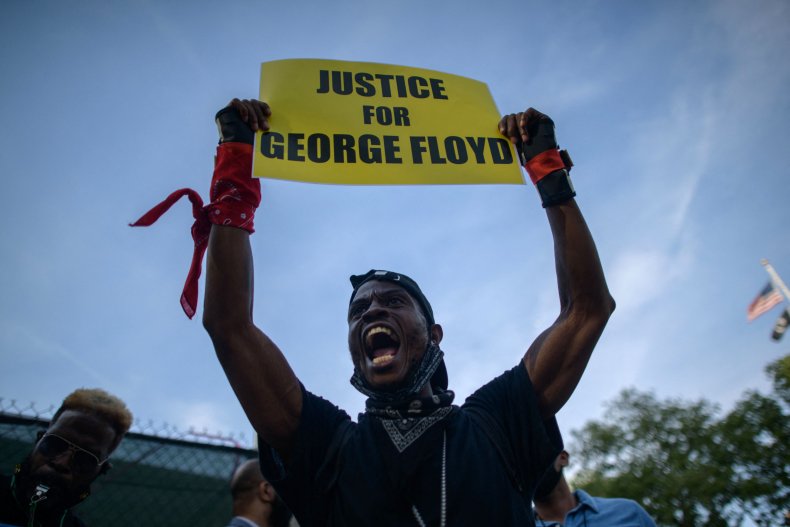

They Still Can't Figure it Out: One Year After George Floyd's Murder | Opinion

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Congress is deadlocked on the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. They're bargaining and can't reach an agreement that protects Black people.

Does it really matter how diverse the George Floyd protests were? Or the numbers of industries that spoke out against racism? And why did it take an almost perfect aligning of stars to gain convictions, given the widespread outrage over Floyd's killing? This nation treks in racial contradictions. And Black folks can hardly catch a breath between them.

Within weeks of George Floyd's murder, folks were praising various displays of support as unprecedented change. Police officers were kneeling with protesters in the streets and even dancing the Cupid Shuffle with them. Democrats were ceremoniously wearing kente cloth stoles during a moment of silence. And the NFL decided to start playing the Black National Anthem.

While some may have been well-intentioned, these acts did not turn the world right-side up with justice for Black people.

The truth is that nothing busies this country more than pandering, or the coddling of racism through kumbaya-type moments. And many went all in on performing and benefiting from it. Much of which has meant justice further delayed and denied, as more Black people are killed.

In this sense, "ain't nuthin' changed, but the year" is how Terrance, 36, of St. Louis explained it. He is a Black male participant I've encountered through my research, who not only described his own encounters with the police but a litany of historical injustices and state responses as "the same song" essentially.

I have spent years, in and out protests, accounting for racially discriminate trends as a sociologist. The kinds that rarely lead to swift actions beyond politicking and performing.

Since the murder of George Floyd, more than 200 Black people have been killed by police. This includes Atlanta's Rayshard Brooks, Brooklyn Center's Daunte Wright, Columbus's Ma'Khia Bryant and Elizabeth City's Andrew Brown, Jr. And this count does not begin to address those injured like Kenosha's Jason Blake, shot seven times in the back and paralyzed.

How does America suppose building trust with the Black community under these circumstances? Where "enough is enough"—but the murders of Black people keep increasing and even overlap?

Nothing could be more egregious than privileged people declaring alliance and change, while Black surviving families are growing in numbers and meeting in solidarity with the newer ones. The Floyds meeting with the Wright family is an example. This is also happening across decades of tragedies. Philonise Floyd, the brother of George Floyd, bonded with Deborah Watts, the cousin of Emmett Till. Meanwhile, state officials keep offering condolences from distant press conference podiums.

This is the pervasive disorder that I account for. It is socially and historically dysfunctional. And as it stands, racial reconciliation across this nation is hard pressed. There has been no true reckoning.

Case in point, over 74 million Americans voted to re-elect a largely anti-Black Lives Matter administration. This matters. It was regardless of George Floyd's televised torture, nationally expressed horror, and ongoing murders and decries from Black America. It's also telling that while Congress is stalled on the George Floyd Act as initially written, Republicans covered most states in a few months, introducing almost 400 restrictive election bills.

This why Karah, a Ferguson protest leader once pronounced through her bullhorn: "They got all these high-profile attorneys that's trained to kill us on paper."

It's because these inconsistencies are not lost on Black people, regardless of political party. They're costing lives, and symbolic to kneeling on the necks of Black America through legal and legislative decisions.

And the Senate's refusal to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Act is but another example. It reveals more of the same—the systemic elimination of Black America through political engagement.

These issues are connected. Police misconduct is a consequence of the broader problem. And it speaks volumes that Black people's right to humanity is still being denied and negotiated, just weeks ahead of Juneteenth—a day commemorating the freeing of enslaved Black people after a two and a half-year postponement, following the Emancipation Proclamation.

The truth is that America cannot square these conflicts. Avoidance and warm, one-off approaches cannot fix this. And campaigns to stifle racial and cultural education only worsens it.

This nation would do best acknowledging historical racism—the ways it lingers and compromises Black lives daily.

Andrea S. Boyles, Ph.D., is an associate professor of sociology and Africana studies at Tulane University. She is the author of Race, Place, and Suburban Policing and You Can't Stop the Revolution.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.