The Daily Guardian is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@thedailyguardian) and stay updated with the latest headlines.

For the latest news Download The Daily Guardian App.

Published

2:11 am ISTon

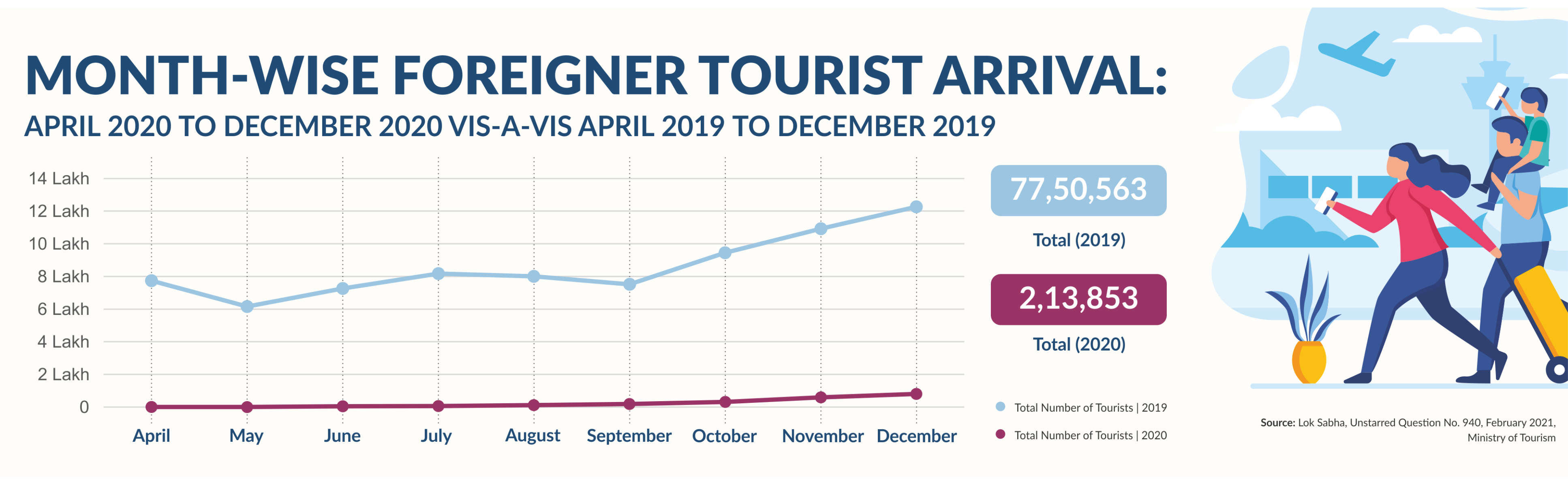

During the Covid-19 pandemic, most industries were forced to adapt to new ways of doing business, as employees began to work from home and customers were approached through online platforms. While some industries tackled this shift quite easily, some others, like hospitality and agriculture, could not make the transition. Service-driven tourism and hospitality is an industry that has next to no provision to be able to continue economic activity remotely. Neither employees nor customers can access these services remotely. One way that this is reflected is by a drop in the number of foreign tourists arriving in India which went from 12 lakh in December 2019 to 470 in April 2020. Even after India and other countries began slowly opening up their borders after the decline of the first wave, only 80,000 foreign tourists visited India in December 2020. While this reflects only one part of the rampage the pandemic has inflicted on the sector, which is heavily dependent on the movement of people across national and international borders, the other part, the domestic tourism sector, has a similar story to tell.

The pandemic has affected lakhs of families as the death count in the country has reached the third highest in the world at 3.29 lakh. The financial impact of the pandemic has affected many more as the economy recorded a negative growth of 7.3% in 2020-21 (provisional estimates of the Central Statistics Office) as the tourism, communications, and transport industries took the biggest hit recording a dip of 18.2% in 2020-21. The microeconomic impact of this decline has manifested in the form of falling demand, consequently, a decline in revenue, and finally, reduction in salaries and increased job cuts. Despite relief measures announced by the central and state governments, it is unclear whether the tourism sector across states – which is one of the biggest sources of employment for millions – will be able to fully recover from the impact of the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Daily Guardian is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@thedailyguardian) and stay updated with the latest headlines.

For the latest news Download The Daily Guardian App.

Published

11 seconds agoon

June 2, 2021WHAT IS HAPPENING TO THE TRAVEL AND TOURISM SECTOR IN INDIA?

Ongoing consecutive “waves” of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns in countries across the world have had an impact on almost every global industry. While no industry, business (big or small), and/or individual has completely escaped the financial impact of the pandemic, some industries have been impacted much more than others. Undoubtedly, one of the most widely affected industries worldwide has been the tourism industry. Tourism is the third-largest export sector in the world, accounting for 7% of global trade (2019). For some countries, tourism accounts for over 20% of overall GDP and is the source of direct and indirect employment for millions.

In November 2020, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) said that by the end of 2020, 174 million people worldwide could lose their jobs if the restrictions on travel continued. Actual figures revealed that 62 million jobs were lost in 2020 and figures published by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) revealed that roughly $1.3 trillion was lost in export revenue in 2020. Tourism is an extremely labour-intensive industry and provides scope of employment for low-skilled workers. While some countries in the world have begun to lift restrictions on foreign and domestic tourist arrivals, India is experiencing a deadly second wave of the Covid-19 crisis and has closed its doors to domestic and international tourists. The travel and tourism industry in the country, accounting for roughly 9% of its GDP (WTTC, 2018), has experienced a sharp decline as tourist footfalls have taken a hit across the country. Most states in India continue to be under lockdown, and even as curbs on movements begin to be lifted, the tourism industry is unlikely to witness an immediate recovery.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic hit India, the tourism and hospitality industry in the country was operating at an all-time high. Travel and tourism is the largest service industry in India and was estimated to be worth $247.37 billion in 2018 as per WTTC data. The industry was the largest Foreign Exchange Earner, with earnings of $29.962 billion in 2019 (y-o-y growth rate of 4.8%). For the same year, the sector contributed nearly $194 billion, around 6.8%, of GDP. In addition to this, the tourism industry accounts for 8% of employment in the country, employing around 39 million people (2018-19). In fact, the government made the industry a major pillar in its “Make in India” program due to its potential for creating jobs. The threat of job losses persists as many jobs are currently supported by government retention schemes and reduced hours, which could be lost without the full recovery of travel and tourism.

With borders closed to foreign and in some cases, even domestic tourists, and the complete shutting down of public places, including hotels and restaurants, the industry fueling the Indian economy in so many ways came to a crashing halt. During the budget session this year, the Minister of State for Tourism said that the total number of tourists arriving in India went from 77.5 lakh during April-December 2019 to 2.13 lakh for the same period in 2020. Foreign tourist arrivals during April-December 2020 registered a decline of 97% as compared to the same period in 2019. Apart from direct revenue generated by foreign tourists and the complete halt of the hospitality sector, domestic and international medical tourism, the MICE (meetings, incentives, conferencing, exhibitions) sector, and MSME output in the tourism sector have all been adversely affected.

In August 2020, Tourism Secretary Yogendra Tripathi said that roughly 2 to 5.5 crore people employed in the tourism sector, directly or indirectly, have lost their jobs in 2020, while the revenue loss in the sector was estimated at INR 1.58 lakh crore. This figure is likely to be much higher in 2021, after the impact of the second wave. The rollout of vaccines in January this year had revived the possibility of increasing domestic tourism, giving those in the industry hopes of a “normal” summer, which is considered to be the peak time of operations for the industry. However, the ravaging impact of the second wave, which swept across the country at a faster speed than the first, took away any chances of a revival. For many in the domestic tourism and hospitality industry, who had hoped to recover losses in 2021 as restrictions were being relaxed, the impact of the second wave and losses could mean final blows to their businesses.

Covid-19 has changed the way people, businesses and countries are approaching tourism with the impact on the industry across the world being unprecedented.

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Published

7 days agoon

May 26, 2021As the deadly second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic continues to ravage India, most Indian states continue to be under lockdown. As of May 24, 2021, the total number of Covid-19 cases in India is 2.68 crores, making it the second-worst affected country in the world, after the United States. India is the largest producer of vaccines in the world, producing around 60% of all vaccines worldwide. Yet at the same time, the inoculation drive for Covid-19, cited by the Indian government as the “largest vaccination drive in the world” which started on January 16, has only been able to fully vaccinate 3% of its entire population. At the current average administration speed of 10.8 million per week, it will take until December 2024 to administer all 2 billion doses of the vaccine.

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Following the announcement of the government on May 1st, that vaccinations would be open to all above the age of 18, around 600 million Indians have become eligible for the Coronavirus vaccine. However, at the same time, several states, including Maharashtra, Delhi, Karnataka, Gujarat, have either temporarily suspended the vaccination program, citing shortage in vaccines, or postponed vaccination drives for those between the ages of 18-44. There has been an overflow of blame and misinformation about the vaccine program and policy. While some blame the shortage on India’s decision to export vaccines, others are stating that the government is increasing dosage gaps simply to buy more time to fix this crisis. In this column, we visit the arguments and misconceptions about the Covid-19 vaccine policy in India to attempt to decipher the various causes of the vaccine shortage in India.

IN BETWEEN THE GAPS: UNDERSTANDING THE INCREASE IN GAPS BETWEEN THE TWO DOSES OF THE CORONAVIRUS VACCINE

The announcement of the increase in dosing interval between the Covishield vaccine earlier this month, at a time when vaccine shortages were reported from multiple states, has raised several questions. While many argue that the increase in gaps between the two doses has been conveniently timed to allow the Indian government to buy more time to fix its vaccine shortage, the government maintains that this decision was based only on scientific evidence.

In January 2021, when the Covishield vaccine was approved for emergency use by the CDSCO, the prescribed gap between two doses of the vaccine was 4-6 weeks. Covishield is Serum Institute of India’s version of AZD1222, the vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford. The emergency authorization of the vaccine was for healthcare workers, followed by frontline workers.

Shortly afterwards, in February 2021, an analysis published in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed general medical journal, revealed that increasing the inter dose gap to eight weeks would yield better clinical results. The study revealed that AZD1222’s efficacy was around 54.9% when the second dose was given less than six weeks after the first dose. The efficacy increased to 59.9% when the second dose was given 6-8 weeks after the first dose, 63.7% when the second dose was at 9-11 weeks, and 82.4% when the dosing interval stretched to 12 weeks or more. The study analysed data from four clinical trials involving 17,177 participants across Brazil, South Africa and the UK. On March 22, following a meeting of the National Expert Group on Vaccine Administration for COVID-19 (NEGVAC), the government issued a recommendation to increase the inter dose gap to six to eight weeks, but no later than 8 weeks.

However, on May 13, the Union Health Ministry announced that the gap between two doses of Covishield was being further increased to 12-16 weeks instead of the earlier 6-8 weeks. This announcement came at a time when several states in India, including Maharashtra, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka had suspended their vaccination drives citing a shortage of vaccines. The government said this increase was based on “available real-life evidence” and “scientific reasons”.

It should be noted India is not the only country that has increased the dosing interval, as in April, Spain also decided to increase the inter dose gap to 16 weeks for vaccine recipients younger than 60 years. As per media reports, NTAGI’s recommendation to increase the inter dose gap was based on the BMJ article, and two additional studies conducted in Bristol and Scotland. While there seems to be some scientific evidence to support the decision to change the gap between the doses of the vaccine, questions about the timing of this announcement, given the reports of shortage of vaccine availability from across the country, are not unfounded.

IS THERE A VACCINE SHORTAGE BECAUSE WE EXPORTED ALL VACCINES TO OTHER COUNTRIES?

Another popular argument floating around about the vaccination shortage in India is rooted in the fact that India exported a significant number of vaccines as part of a global diplomacy program when only less than 5% of its own population is fully vaccinated. Is this true? Let us find out. Under its Vaccine Maitri programme, India has exported and donated more than 66 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines to 95 countries worldwide. It is critical here to distinguish between donations of vaccines, and the commercial obligations of vaccine manufacturers to export vaccines. Out of 66 million, 10.7 million exports were grants from the government, 20 million were as a part of the global COVAX facility, and 36 million were commercial exports.

Out of the 10.7 million doses that have been donated as aid, 7.85 million doses have been donated to neighbouring countries, while 200,000 doses have been given to UN Peacekeeping forces.

India was certainly not the only country exporting vaccines. China exported 240 million vaccines to 60 countries, however, only after it had managed its own COVID 19 crisis. Additionally, the EU has also exported 200 million vaccine doses to 43 countries, but the EU is made up of 27 countries. In comparison, it certainly can be argued that India has exported a significant amount of vaccines when compared to other countries. In fact, one of the worst affected countries by the COVID 19 pandemic, the United States, through the use of its Defense Production Act, made domestic production and use of COVID-19 vaccines its priority, refusing all exports. At the end of March 2021, citing a shortage of vaccines available, India suspended exports. The government further acknowledged that vaccine shortages in India will persist at least until July 2021. The Serum Institute of India (SII) , which is the largest single supplier to the COVAX scheme, has also not made any of its planned shipments since the suspension of exports in March. The SII is a part of the international COVAX scheme run by Gavi, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and WHO to ensure equal access to COVID-19 vaccines.

While donating vaccines to neighbouring countries certainly contributed to the shortage of vaccines in India, the main question that arises is: has the Indian government ordered enough vaccines in the first place? Several policy experts have cited that India’s delay in placing large scale orders for vaccines is the main reason for the shortage of the vaccine across the country. The first purchase of the vaccine (only 16 million doses) was placed in January, while the first large-scale purchase came in March, of 100 million doses from Serum Institute and 20 million from Bharat Biotech. It placed an additional order of 160 million doses from the two companies to be delivered by July. Other countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom placed their first preliminary orders of the vaccine as early as May 2020.

POLICY OF BUYING AND DISTRIBUTING VACCINES IN INDIA HAS BEEN UNCLEAR FROM THE BEGINNING

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Even now, India has ordered only around 350 million doses of the vaccine, which is sufficient to fully vaccinate 175 million people which is around 12% of the entire population of the country. In comparison, as per data supplied by the Duke Global Health Innovation Centre, the United States has ordered 1.2 billion doses of the vaccine (enough to vaccinate 2 times over), Canada has ordered 338 million (5 times over) and the United Kingdom has ordered 457 million doses (3.6 times over). A senior fellow writing at the Center for Policy Research criticized the ordering policy of the Indian government and said instead of placing large bulk orders, the government is “buying vaccines like monthly groceries”.

The policy of buying and distributing vaccines in India has been very unclear from the beginning, and the government did not address the issue of increasing vaccine supply and buying more stocks before opening up larger populations who would now get vaccinated.

India is the only country in the world where the Central government is not the sole buyer of vaccines and one of the few where vaccinations are not free for all. In April 2021, the central government announced that the states would be responsible for procuring vaccines for the 18-44 age group and that the prices for procurement would be pre-declared by the vaccine manufacturers themselves. Following reports of shortages, governments of Delhi and Punjab alleged that they reached out to international vaccine suppliers Pfizer and Moderna, who refused to send vaccines directly to the state, and stated they shall only deal with the central government.

The confusion does not seem to end there. Many states are also still struggling to dispense the available vaccine stocks. As per a Press Information Bureau release dated May 11, more than nine million Covid-19 vaccine doses available with states and Union Territories are yet to be used. Additionally, since the start of the vaccination drive in January 2021, 4.6 million doses of the vaccine have been wasted as per data shared by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) in response to a Right to Information (RTI) query. As of March 2021, the state with the highest wastage was Telangana (17.6% wastage) followed by Andhra Pradesh (11.6%) and Uttar Pradesh (9.4%). Vaccine wastage can occur at three levels: during transportation of the vaccine, during cold chain point and at a vaccination site — both at service and delivery levels. On the other hand, eight states, including Kerala, West Bengal, Himachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Goa, Daman and Diu, Andaman and Nicobar Islands as well as Lakshadweep have reported ‘zero wastage’, highlighting the importance of reducing vaccine wastage at a time when there is a shortage in supply of vaccines throughout the country. Additionally, as per medical experts, there are over 12 companies and institutions in India that have the capacity and resources to scale up the production of Covishield or Covaxin, to help with the supply crunch. These facilities could have been ramped up to produce more vaccines.

Contributing reports by Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat and Bhumika Parmar, Raunaq Sharma, Sehal Jain, Interns at Polstrat.

Published

4 weeks agoon

May 5, 2021

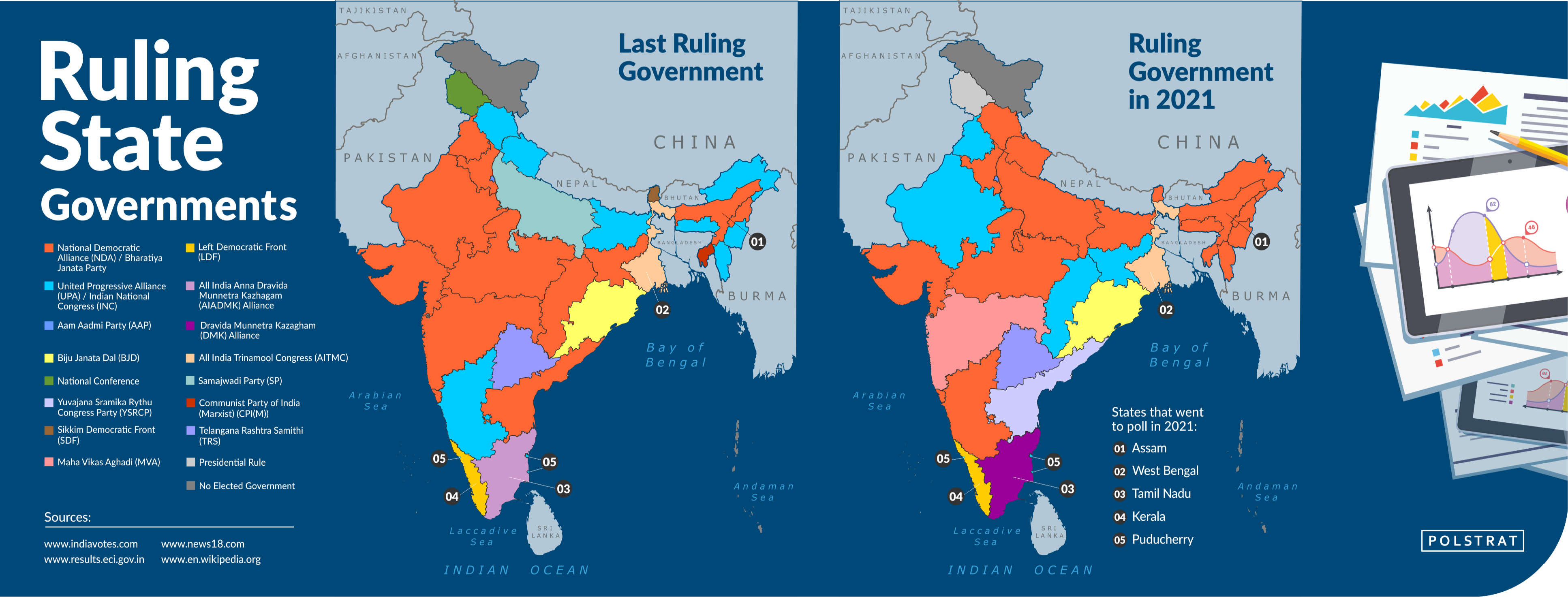

WEST BENGAL: DIDI’S THIRD TERM

In a widely scrutinized and highly contested battle, incumbent Chief Minister Mamata Bannerjee led the All India Trinamool Congress (AITC) to victory in the 2021 Assembly Elections. Despite having to battle against high anti-incumbency sentiments, electoral machinery of the BJP, and some widely publicised defections from top party aides, Banerjee successfully led the AITC to victory, securing 213 out of the 292 seats that went to poll. The AITC managed to increase its seat share by 2 seats and it’s vote share also increased to 47.95% this time, a surge from 2019 (43.70%) and 2016 (45.60%).

Although the Chief Minister lost her own seat, Nandigram, to long-time protege and now BJP member Suvendu Adhikari with a margin of merely 1,736 votes, the party’s large scale victory is all anyone can seem to talk about. What is also noteworthy is that the party also managed to secure a victory in minority-dominated regions of Malda and Murshidabad, which directly affected the Left-Congress’ position.

The BJP, which emerged as the principal opposition party, failed to secure the kind of victory it hoped for and had to settle with 77 seats and a vote share of 38.12%. In 2016, the BJP had managed to secure just 6 seats and a vote share of 10.80%. This changed significantly during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, when the party, which had almost no political footprint in the state secured 18 seats. However, the party’s vote share has come down by 2.58% from 40.7% votes in 2019 to 38.12% in 2021. The 18 seats won by the BJP account for about 121 Assembly seats, out of which it was only able to retain only half of the seats, and the TMC won the remaining 60. In addition to this, the BJP’s vote share in those seats also fell by 10% from 2019 to 2021.

Given the high intensity campaign of the BJP, using star campaigners such as Prime Minister Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah, the party failed to reach anywhere near the mark of 200 it had speculated. Undoubtedly, the party’s failure to have a clear Chief Ministerial candidate and public failure in containing the second wave of the Covid-19 crisis has played a role in the elections.

The Left-Congress-ISF alliance or the Sanjukta Morcha, locally called the jot, was nearly wiped out in the state, managing to win just one seat and securing a combined vote share of 8.6%.

The Left Front, which ruled the state for 34 years until Mamata Bannerjee unseated it in 2011, not only fell drastically short of its 2016 vote share of 21.18% but also failed to retain its vote percentage from the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Both the Left and the INC will not have even one single MLA in the 294 seat assembly, with the only seat that the Samyukta Morcha will represent being in favour of ISF chairman Naushad Siddique from Bhangar.

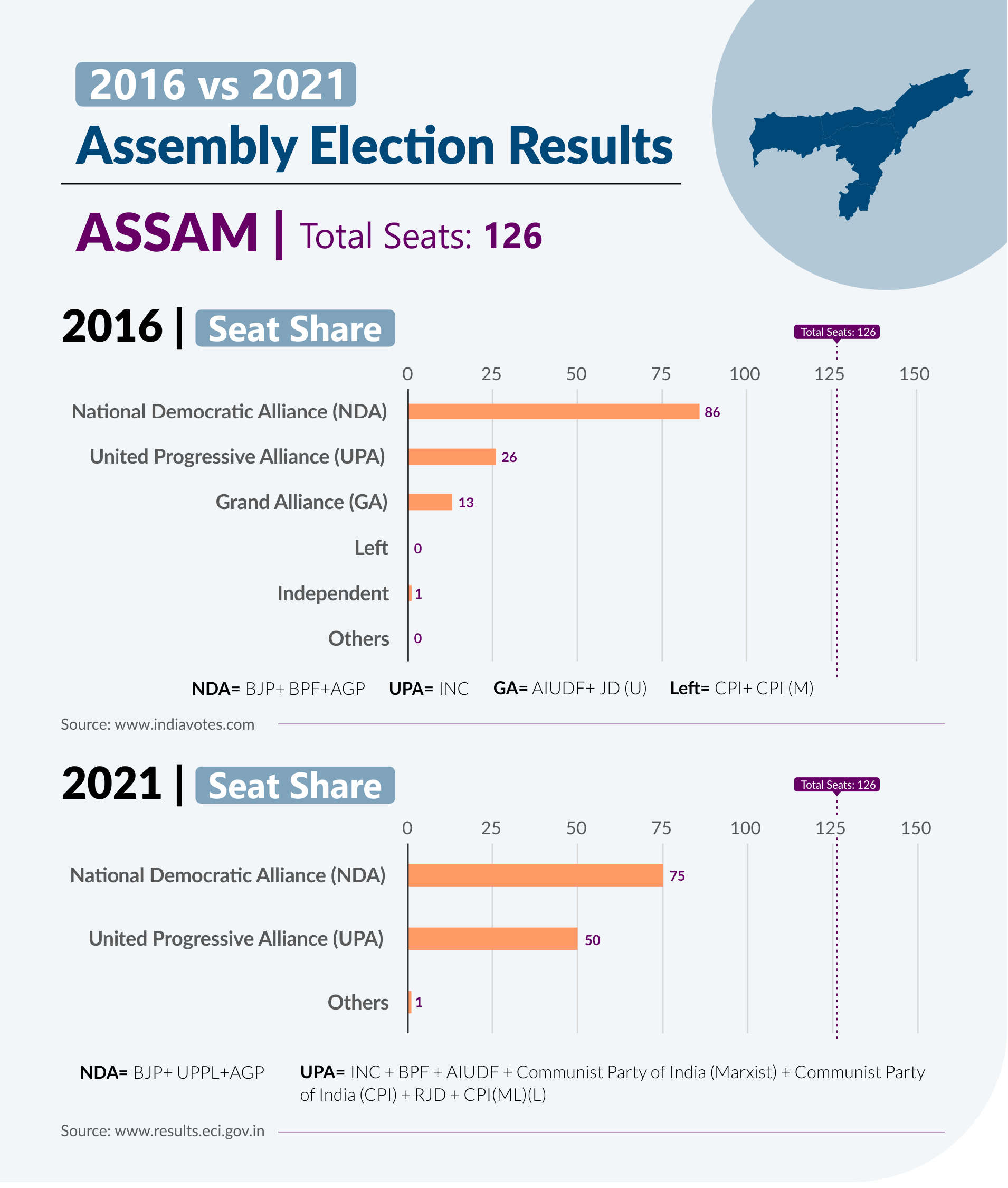

ASSAM: BJP’S SILVER LINING IN 2021

As the counting of votes continued on May 2nd, perhaps the victory in Assam was the only consolation for the BJP, as it secured a very comfortable win in the state election. While the anti-CAA and NRC protests led to the emergence of new parties and alliances such as the United Regional Front and the Congress’s Mahajot in an effort to win the state back, BJP managed to keep control of the state, winning a staggering majority of 75 seats in the 126 seat assembly.

However, this marks a loss of 11 seats since the last time when the alliance secured a win in 74 seats and a vote share of 38% (excluding 12 seats and 4% vote share of BPF). Individually, the BJP maintained its previous tally of 60 seats but increased its vote share from 29.8% in 2016 to 33.21% in 2021. When compared to its 2019 vote share, the BJP lost 3.19%.

Pre-poll alliances also saw major shifts when BJP’s long-time ally Bodoland People’s Front (BPF) left the NDA to join the UPA. The party’s seat share reduced from 12 seats in 2016 to 4, and its vote share also declined from 4% in 2016 to 3.39% in 2021. The Congress, which was fighting to gain back power in the state only managed to secure 29 seats, increasing its seats in the assembly by 3, whereas its vote share came down slightly with a loss of 1.63% (29.7% vote share in 2021). Its ‘Mahajoth’ allies AIUDF won 16, and Bodoland People’s Front bagged four seats with a combined vote share of 12.68%. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) secured one seat with 0.84% of votes whereas the Communist Party of India (CPI) failed to gain a seat.

Although the BJP-led NDA is slated to form a government for the second consecutive term, it is unclear if incumbent CM Sarbananda Sonowal (who won from Majuli) will continue in his position. This is even more uncertain since after the former Congress leader Himanta Biswa Sarma joined the BJP in 2015 and has bagged the Jalukbari seat with a margin of over one lakh votes and won an assembly seat for the fifth consecutive time and has a key role in expanding the party’s fortunes in the state.

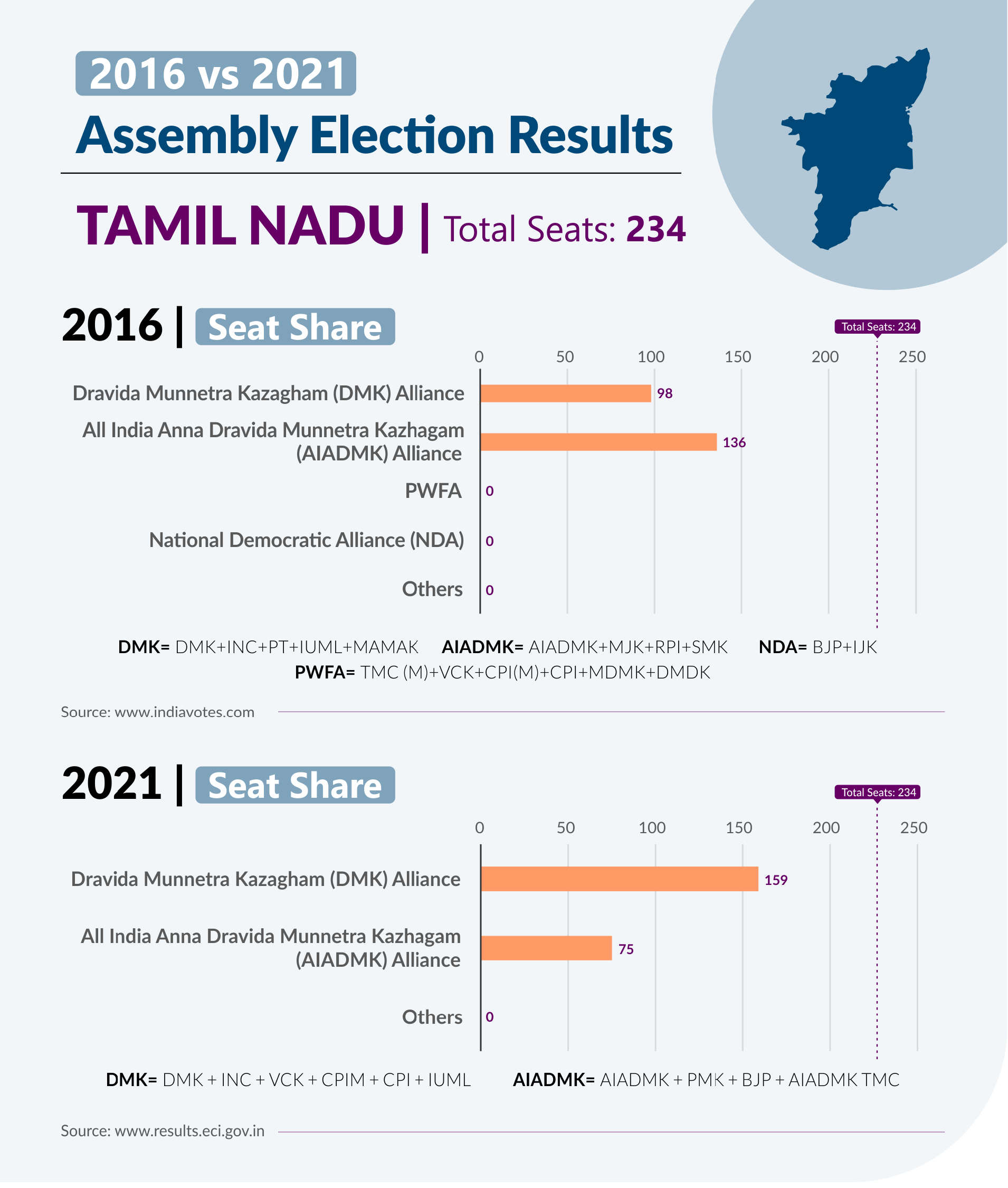

TAMIL NADU: MK STALIN FINALLY SET TO BE CHIEF MINISTER

MK Stalin, the son of Muthuvel Karunanidhi and the leader of the DMK, will finally take his position as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, a position that he has perhaps been waiting for over two decades. Breaking the 10 years of AIADMK rule in the state, the DMK-led alliance has secured a majority in the state, winning 159 seats in the 234 seat assembly. The elections also reaffirm the bipolar nature of politics in the state as there will be no candidate from outside the two dominant alliances led by DMK and AIADMK, represented in the legislative assembly.

The results mark the rise of the DMK alliance since the 2019 LS elections when it wiped out the AIADMK-led NDA by winning 35 of 38 seats leaving just one seat for the NDA. The DMK individually won 133 seats in the 2021 elections, marking an increase of 44 seats from the 89 seats it secured during the 2016 elections. The DMK-led alliance’s vote share has increased from 39.30% in 2016 to 44.39%, however, it has declined from the 50.90% it managed to secure during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. The INC, which is also a part of the DMK alliance has increased its MLA count in the state to 18. However, its vote share has declined from 6.5% in 2016 to 4.28% this time.

Although the AIADMK-led NDA managed to secure 75 seats in 2021, this was a major decline from the 126 seats it secured in 2016. In terms of vote share, the NDA, which includes AIADMK, BJP & PMK, bagged 39.72%, a rise of nearly 9.02% points from 30.70% in 2019. When compared to 2016, the alliance clocked a loss of a small 2.08% from 41.80% in 2016. The BJP opened its account in the state for the first time in 20 years by winning 4 seats with a vote share of 2.63% which was still a drop from 3% in 2016.

Although around 14.46% of the vote share went to parties other than those in the two major alliances, they will not be sending any MLA to the assembly. Popular actor Kamal Hassan who floated his own party Makkal Nidhi Maiam failed to win any seat in the 234 seat assembly. Similarly, The TTV Dhinakaran-led AMMK and its alliance partner Vijayakant-led DMDK also failed to gain a single seat in the assembly.

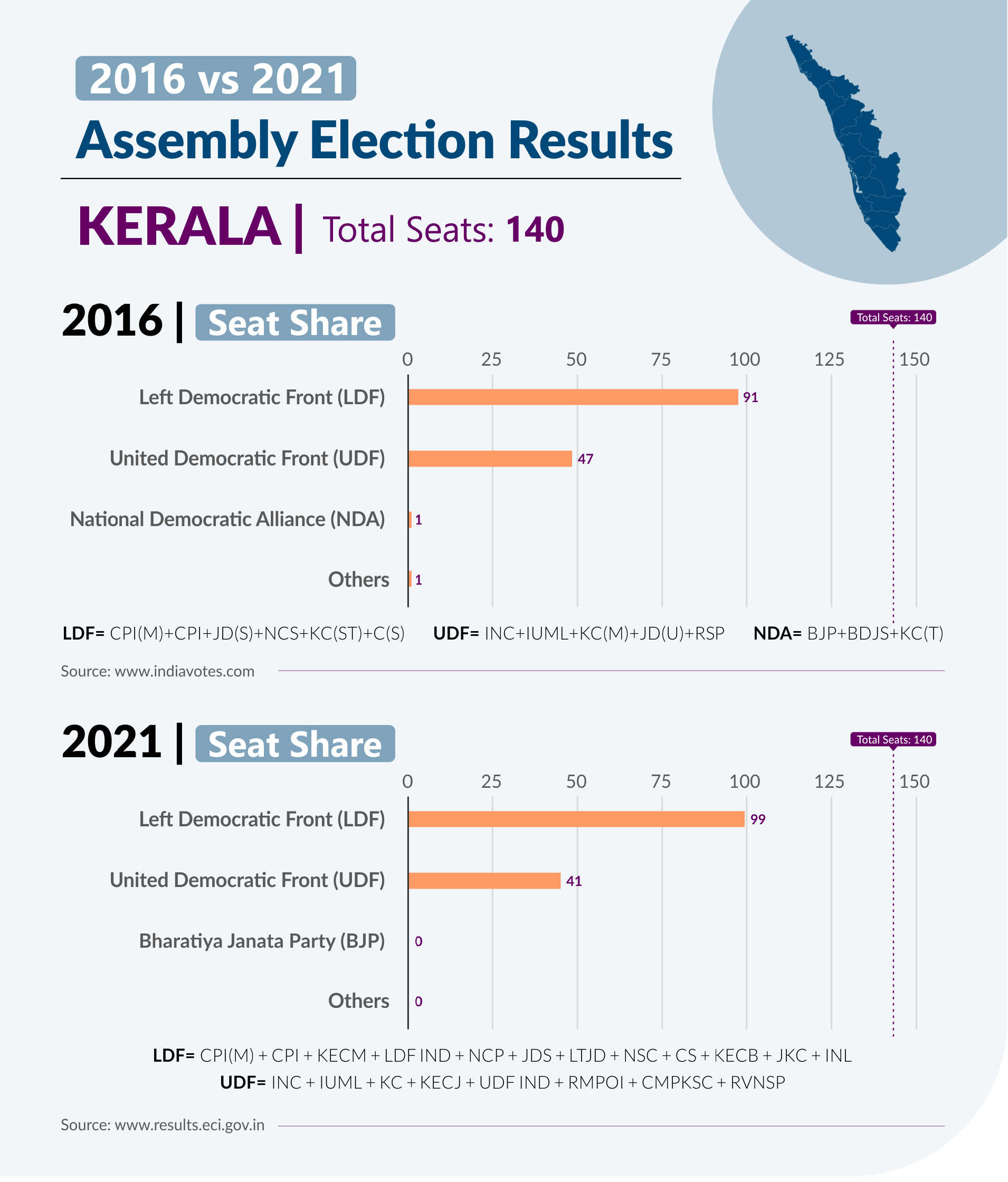

KERALA: LDF BREAKS 40-YEAR CYCLE OF ANTI-INCUMBENCY

Marking a huge change in politics, the state, for the first time in 40 years is slated to beat anti-incumbency and elect the same party to power for a second consecutive term. The incumbent Left Democratic Front (LDF) led by 76-year-old CPI(M) leader Pinarayi Vijayan won 99 seats in the 140 seat assembly, a gain of 8 seats from the last assembly elections. The LDF, which had managed to secure a vote share of 43.48% in 2016, increased it to 47.60% in 2019, however, this has now dropped again to 37.5% in 2021.

The main opposition alliance, the United Democratic Front (UDF) led by Congress focused its campaign in the state on highlighting the “mistakes” of the LDF government, including the gold smuggling scandal and the Sabarimala verdict. However, it only managed to secure 41 seats, a fall of 6 seats as compared to 2016. The UDF’s vote share also declined from 38.81% in 2016 and 47.60% in 2019 to 36.6% this time. The INC, which individually won 22 seats in 2016 saw a loss of 1 seat this time but increased its vote share by 1.32% to 25.12%. When comparing to its vote share of 37.5% in 2019, the party was at a major disadvantage.

The BJP-led NDA which had one seat in 2016 with a vote share of 14.96% failed to retain it, winning no seats at all this time, and bagging a reduced 11.30% vote share despite the party sending major names like Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Amit Shah to rally for the candidates in the state.

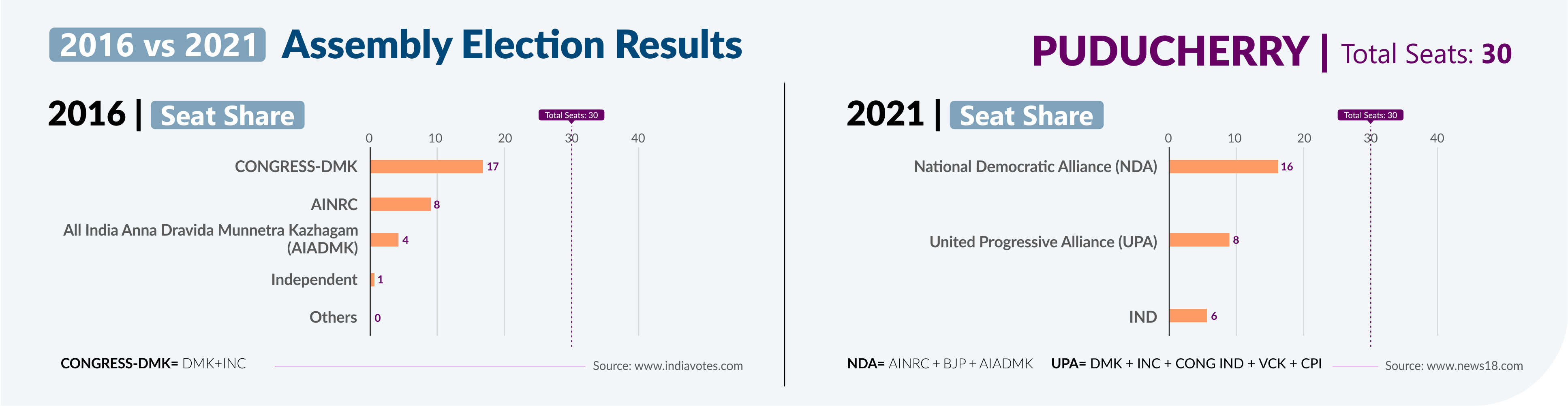

PUDUCHERRY: CONGRESS FAILS TO WIN BACK ITS LAST SOUTH CITADEL

The INC government in the Union Territory of Puducherry, which was one of the last citadels of the Congress in the south, collapsed a month before the U.T. was set to go to polls. The U.T., which was currently under President’s Rule opted for a change in government, with the All India N.R. Congress (AINRC) winning 16 seats. The contest in Puducherry was a two-pronged battle between the Congress-DMK alliance and the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) comprising the All India NR Congress (AINRC), the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

As a part of the NDA, the AINRC individually won 10 seats, while the BJP won 6. The AIADMK, which is also part of the alliance, did not manage to secure a single seat in the state. The DMK and the Congress, on the other hand, won six and two seats respectively. This was a decline for the INC, which had wrested control of the U.T. from the AINRC in 2016, managing to secure 15 seats, and forming a government with the support of the DMK, which had won 2 seats.

WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM DAMINI MEHTA, JUNIOR RESEARCH ASSOCIATE AT POLSTRAT.

Published

1 month agoon

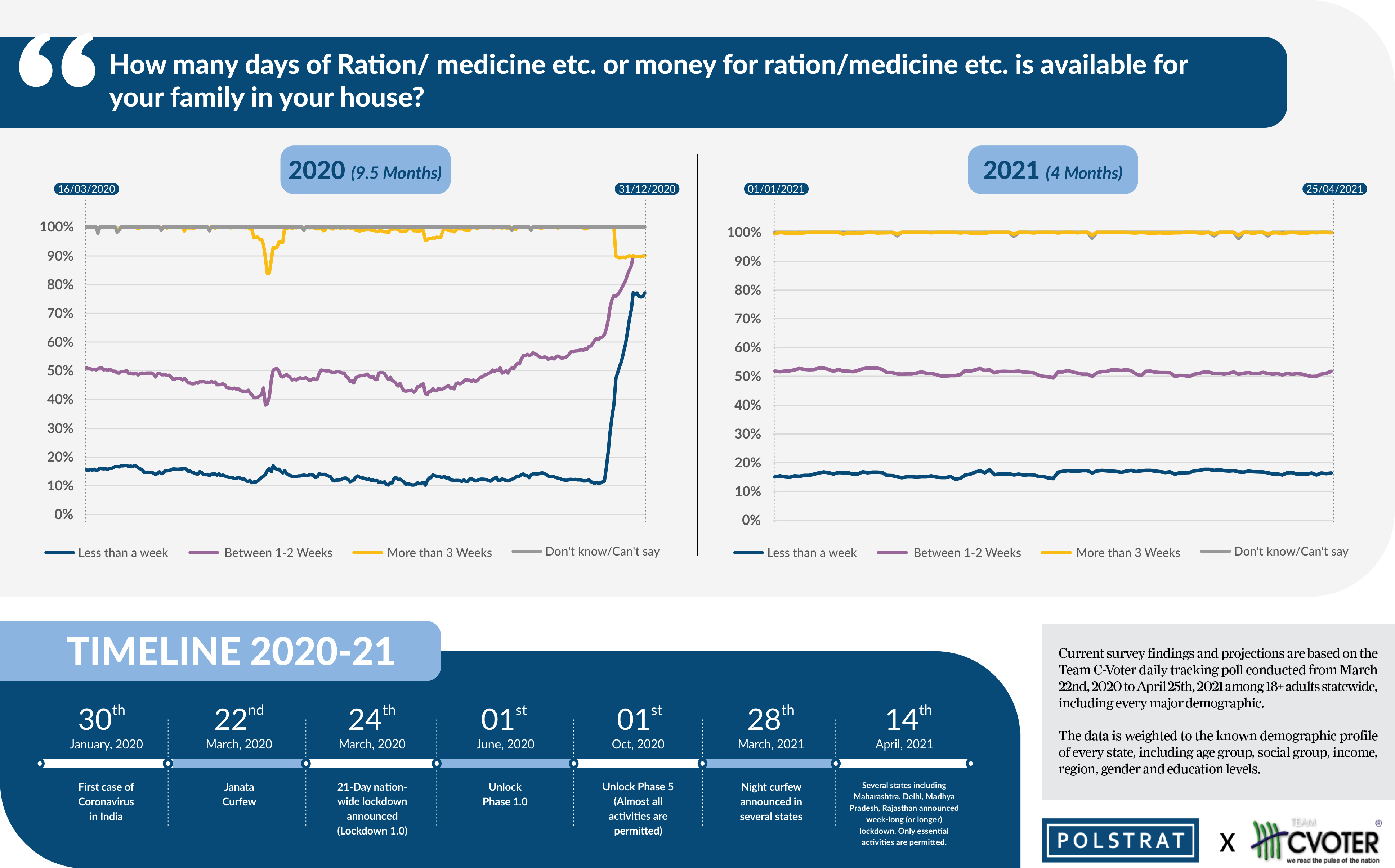

April 28, 2021In an attempt to capture the country’s sentiment on the coronavirus crisis, Team C-Voter has been conducting a daily tracking poll from March 16th, 2020 among 18+ adults statewide, including every major demographic. The poll asks questions to respondents across the country about their economic and social well being, along with their sentiments on the fear of the virus and availability of food/ration in their households.

In mid-September 2020, since COVID cases reached a peak of more than 93,000 per day, infections began to decline steadily. By the middle of February 2021, India was only recording an average of 11,000 cases a day. In fact, in early March India’s health minister Harsh Vardhan said the country was “in the endgame” of the pandemic. However, in less than a month the situation changed drastically and the country is in the grips of a deadly second wave of the virus.

As of mid-April, India is experiencing a record-high rise in the daily number of cases every day. On 26th April, India recorded 3.52 lakh new COVID cases in a 24-hour period, the highest daily case count recorded in any country since the discovery of the virus in China more than a year ago. The country is now experiencing a major public health emergency as reports are coming in from all states about shortages of oxygen, ICU beds, ambulances, and essential medications. Using the Team C-Voter daily tracker, we will break down the changes in public opinion about the fear of the coronavirus and public approval of the government’s handling of the past few weeks as compared to the first wave of the virus in 2020.

HOW HAS THE PUBLIC OPINION ABOUT THE THREAT OF THE CORONAVIRUS BEEN CHANGING?

In 2020, during the months of April and May when India was under a series of strict lockdowns, the percentage of people who were scared of getting the coronavirus stabilized at around 41-45%. These numbers began to increase after the announcement of the lockdown relaxations and the unlock phase in the country, reaching an all-time high average of around 60% in August and September 2020. However, since the first week of October, the percentage of those who were scared that they or someone else in their family could catch the coronavirus began to decline.

In January 2021, the percentage of people who said that they were scared that they or someone else in their family could catch the coronavirus was at an all-time low of around 35%. Such low percentages were only recorded before in March of 2020 before the announcement of the Janata Curfew and the subsequent country-wide lockdown. These numbers went as low as 27% towards the end of February when the general public perception seemed to be that India had “defeated” the pandemic.

However, since the last few weeks in March, the fear of the virus has increased substantially once again as the total number of positive cases is touching an all-time high. Around 50% of people have said they fear that they or someone else in their family could catch the coronavirus in the past few weeks. As of April 2021, India is the second-worst affected country in the world by the coronavirus.

HOW HAS INDIANS’ APPROVAL OF THE GOVERNMENT’S HANDLING OF THE CORONAVIRUS BEEN CHANGING?

In 2020, in the days leading up to the Janata Curfew on March 22nd, around 75% of Indians believed that the government was handling the coronavirus crisis well. After the announcement of the first nationwide lockdown on March 24th, this figure began to increase gradually. However, it wasn’t until the first few days of April that over 93% of the respondents said that they thought the government was doing a good job in handling the crisis. This high approval rating continued until the end of May. However, since the announcement of the opening-up of the economy and the subsequent announcement of the unlock phases in June 2020, the percentage of those who agree with the way the government has been handling the crisis had been declining, reaching around 78% towards the end of the year.

Nonetheless, throughout the months of January and February 2021, the percentage of people who agreed with the government’s handling of the coronavirus crisis stabilized at around 80%. This relatively high approval rating continued till the end of March. However, since the last few weeks in March, once again the approval of the government’s handling of the crisis had begun to decline gradually as cases continued to touch record-highs every day. On 21st April, India recorded 312,731 new COVID cases in a 24 hour period, the highest daily case count recorded in any country since the discovery of the virus in China more than a year ago.

While some states such as Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Delhi have lockdown restrictions in place to prevent the explosive spread of the virus, no nationwide lockdown has been announced. India is now grappling with a major public health emergency as reports are coming in from all states about shortages of oxygen, ICU beds, ambulances, and essential medications. However, during an address to the nation, on April 20th, Prime Minister Narendra Modi urged states to announce a lockdown only as a “last measure”. On April 25th, 2021, the percentage of people who approve the government’s handling of the crisis fell to 68.8%. This is the lowest it has been since the start of the pandemic last year in India. During the first wave in 2020, this figure was as high as 94%.

As we can see, the shortage of medical supplies, including necessary medication, oxygen and ICU beds has caused a dip in Indians’ approval of the government’s handling of the coronavirus crisis. In the past few weeks, there has been a huge shortage in availability of oxygen cylinders and tankers which are necessary for transportation of oxygen from manufacturers to hospitals and individuals. This has created a massive shortage in availability of oxygen, which is highly demanded by COVID 19 patients who require urgent oxygen support.

HOW HAS THE AVAILABILITY OF RATION/FOOD IN INDIAN HOUSEHOLDS CHANGED DURING THE CORONAVIRUS LOCKDOWN?

In the days leading up to the Janata Curfew on March 22nd, over 75% of Indian households only had ration/money for ration to last them for less than a week. However, after the announcement of the first nationwide lockdown on March 24th, households gradually began to stock up, with only around 22% having ration/money for ration for less than a week by April 4th.

It is critical to note that throughout various phases of the lockdown, during the months of April and May, roughly 11-13% of Indians still reported having ration/money for ration for less than a week. For a country of 1.35 billion, this would translate to around 150- 175 million people who were living hand to mouth throughout the lockdown period. Even after the opening up of the economy on June 1st, and the subsequent start of the unlock period on June 8th, the majority of Indian households continue to be stocked up, with over 50% of them having enough ration for more than 3 weeks. This trend continued till the end of the year, with roughly 50% of households stating that they had food/money for food for more than 3 weeks, while around 15% were living hand to mouth, with food/money for enough supplies only to last them for less than a week.

Towards the middle of April, as coronavirus cases skyrocketed across the country, several states, including Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Delhi, Punjab, and Karnataka imposed severe restrictions, eventually leading to the announcement of a complete lockdown. When comparing the figures from 2020 and 2021, we observe that throughout April and May in 2020, when a strict lockdown was ongoing in the country, the percentage of people who said they only have ration/money for ration for less than a week was around 11-13%. On the other hand, in 2021, from the end of March till mid-April (as restrictions are being put in place) this percentage is slightly more at around 15-17%. Once again, to put this into perspective, for a country of about 1.35 billion people, this would translate to around 200-215 million people who are now living hand to mouth as a result of the lockdown imposed to curtail the spread of the second wave of COVID-19.

India is currently experiencing a deadly second wave of coronavirus crisis and as we continue to be under lockdown to fight the spread of the disease, another need is to fight against the spread of misinformation and inaccurate perception which can be as deadly as the virus. Our team at Polstrat hopes that everyone is staying safe and following all government guidelines to help curtail the spread of the virus. Through our tracking poll, we will continue to keep you updated on changes in public perception of the virus.

Current survey findings and projections are based on the Team C-Voter daily tracking poll conducted from March 22nd, 2020 to April 25th, 2021 among 18+ adults statewide, including every major demographic.

The data is weighted to the known demographic profile of every state, including age group, social group, income, region, gender and education levels.

Published

2 months agoon

April 17, 2021

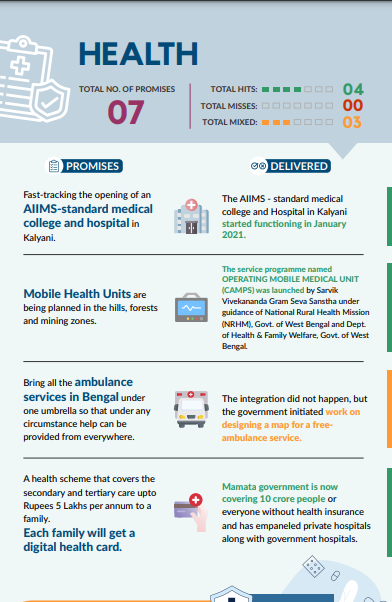

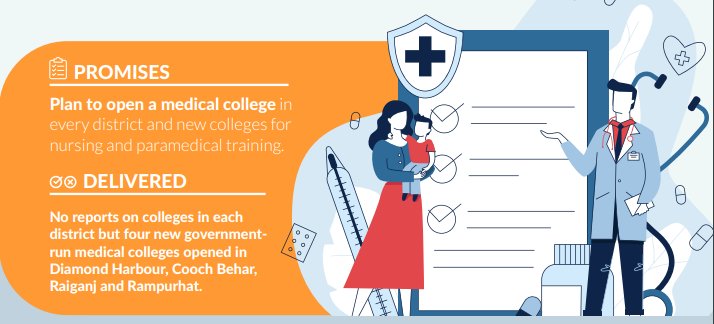

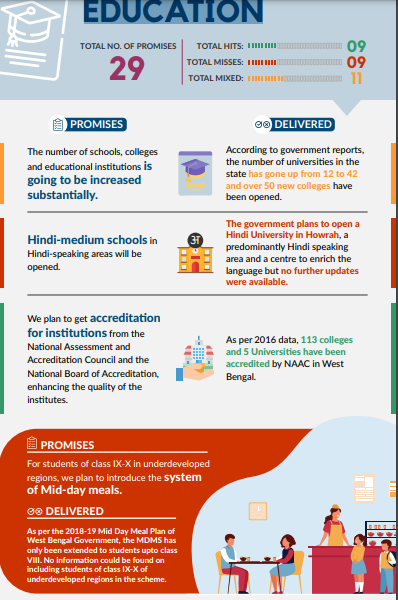

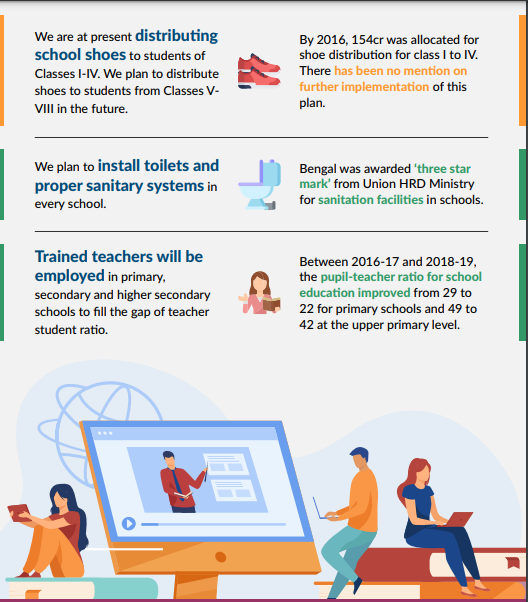

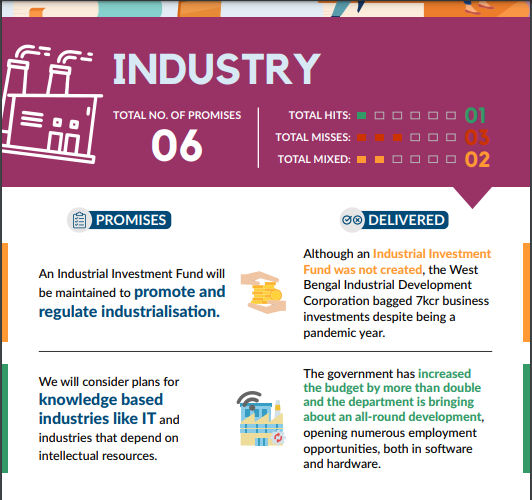

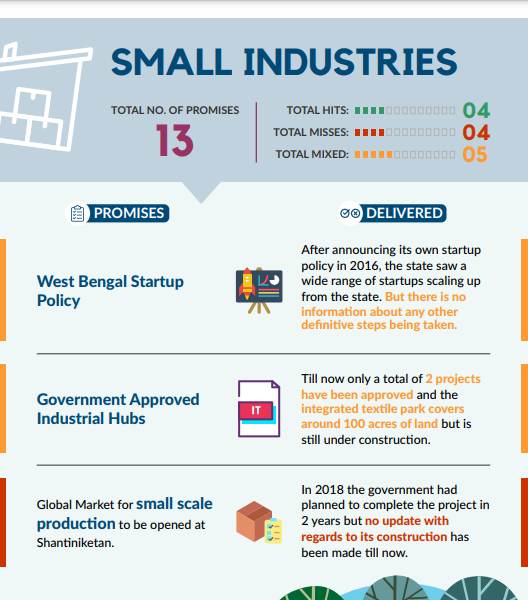

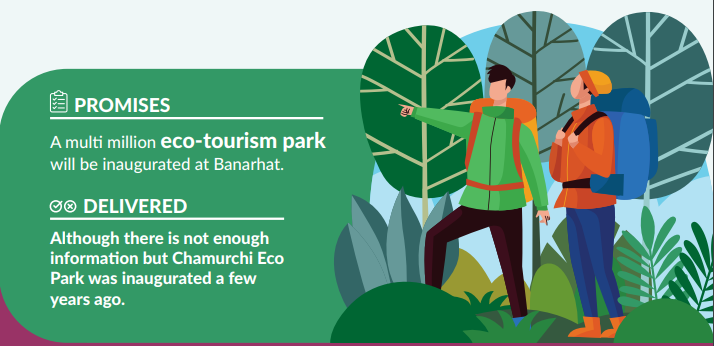

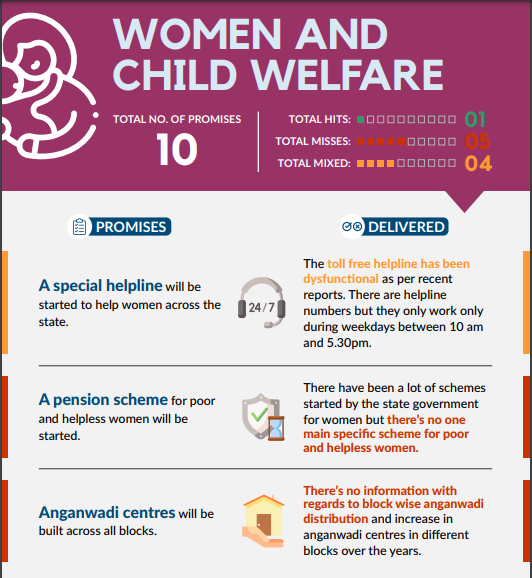

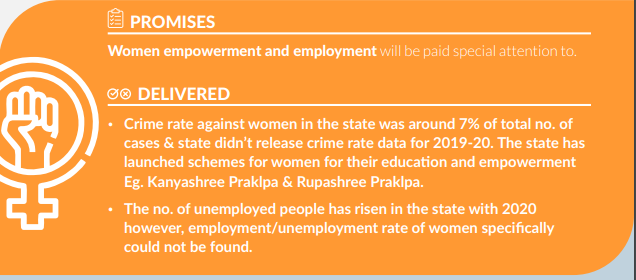

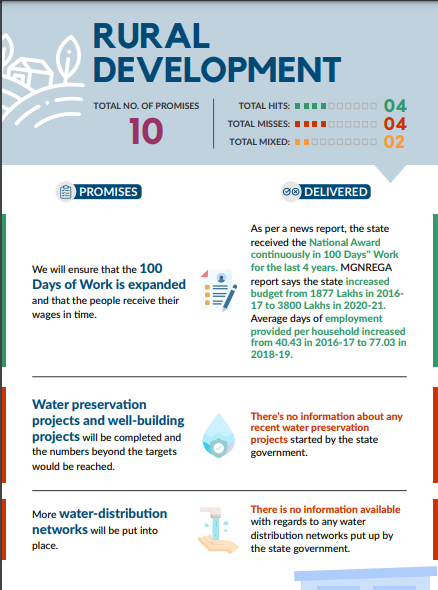

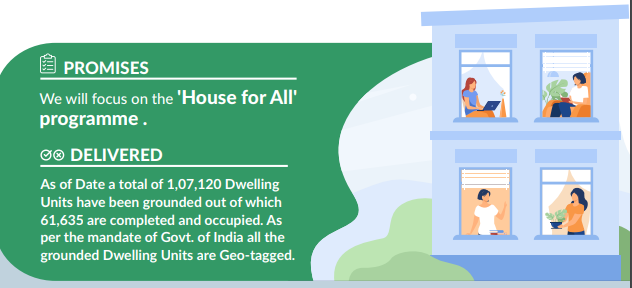

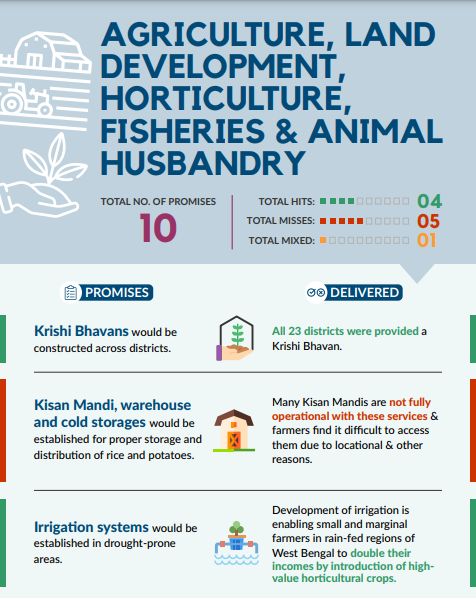

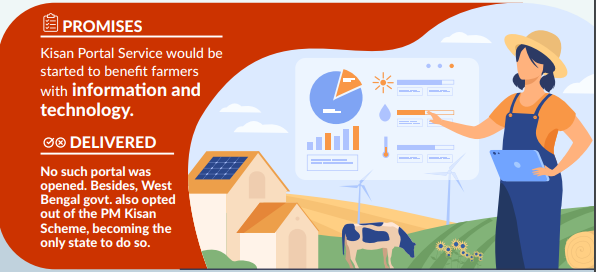

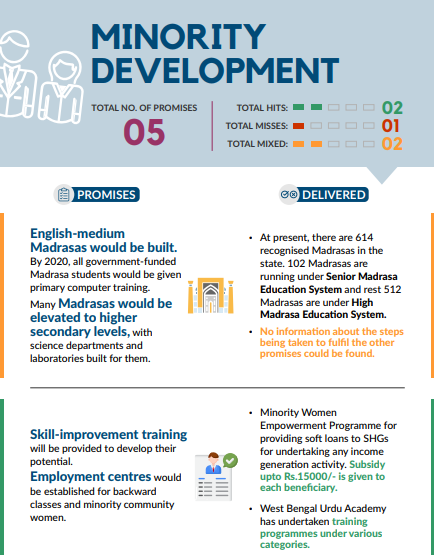

POLSTRAT MANIFESTO CHECK WEST BENGAL

Published

2 months agoon

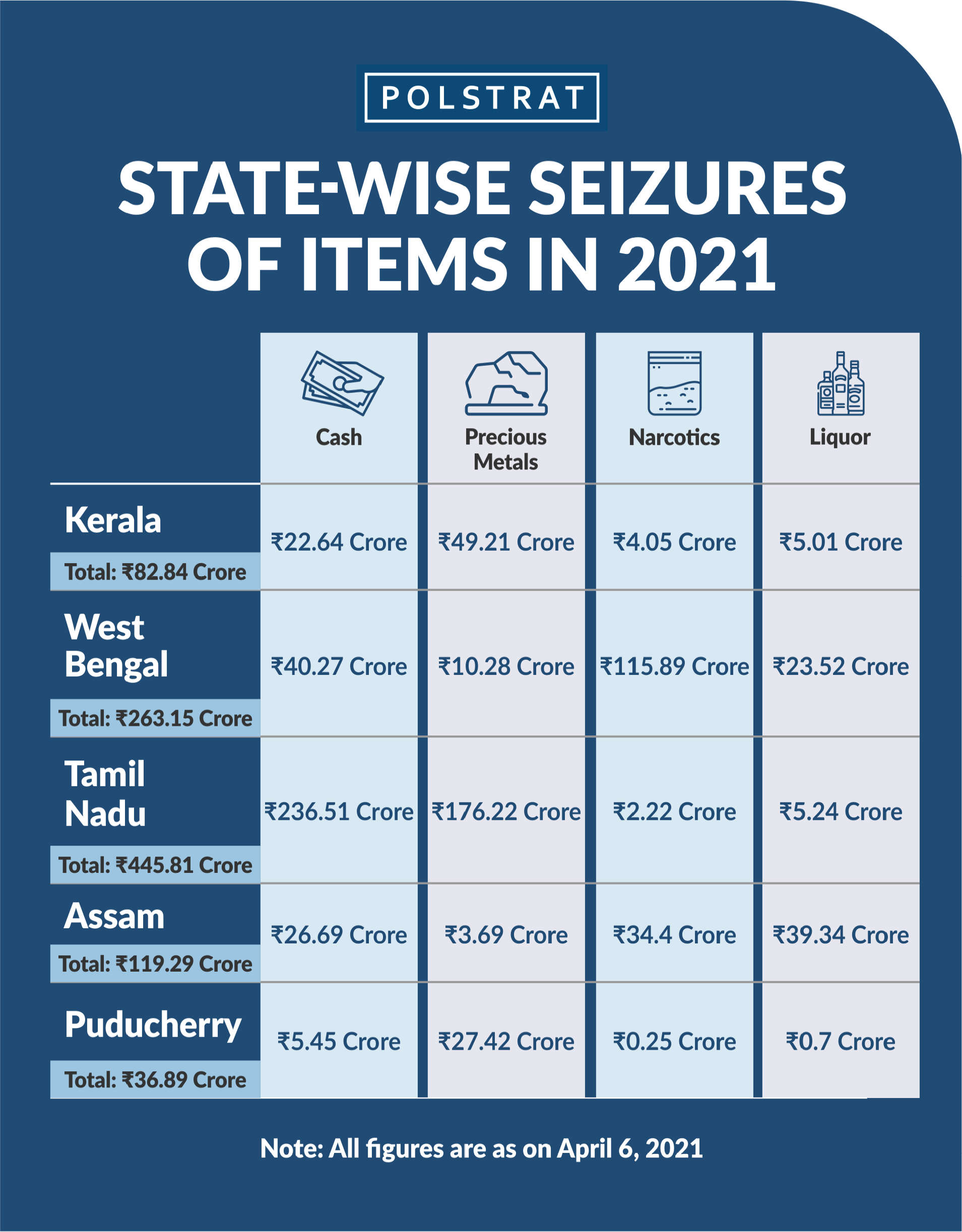

April 14, 2021On April 6th, as voting closed for assembly elections in various states in India, including Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, West Bengal and Assam, reports of clashes between political parties from almost every part of the country came to light. Parties accused each other of buying votes for cash, liquor, freebies and of orchestrating electoral fraud by tampering with electronic voting machines (EVMs).

Such allegations during any election in India are not new at all and have become a standard feature of every bypoll, assembly and state election in India. Another common form of electoral malpractice in India is the violation of the model code of conduct as prescribed by the Election Commission of India (ECI).

The ECI, a constitutional body under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Law and Justice, the Government of India is responsible for the conduct of elections at the national level, state level and local level.

The ECI is responsible to ensure that any instances of electoral malpractice and fraud are kept under check as per various laws to ensure that everyone has a level playing field. Let us take a deep dive into these accusations and find out what is the truth behind them.

WHAT IS THE PRICE OF A VOTE IN INDIA? BARTER FOR CASH, LIQUOR, GOLD FOR VOTES

On 5 April, before the single-phase voting was set to begin in Tamil Nadu, residents of a village in Namakkal district held a protest. The reason? The protesters alleged that they had been left out when a political party was distributing cash for votes for polling the next day. Clashes were witnessed on polling day between several political parties in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala accusing each other of giving out cash for votes. Undoubtedly, distributing cash and other freebies such as liquor, narcotics for votes has become a commonplace practice in Indian elections.

The distribution of any cash, gifts, liquor or other items is not permitted when the election model code of conduct is in force by the Election Commission of India. It falls under the definition of ‘bribery’ — an offence under Section 171 (B) of IPC — and Representation of the People Act, 1951. However, despite this, as per data provided by the ECI, roughly three times as much cash, liquor, narcotics and other freebies have been seized so far in 2021 as compared to during the assembly elections in 2016 in the same states.

Till April 6th (before the day of polling) the ECI has roughly seized unaccounted cash, liquor, narcotics, precious metals and other freebies worth Rs. 948 crores from all poll-bound states. In 2016, the same figure was at around Rs. 226 crores. Out of all the freebies seized, cash accounted for the highest percentage (Rs. 331.56 crores), followed by precious metals (Rs. 226.82 crores).

In fact, the exchange of cash and freebies for votes is so common that many politicians have talked about the “going rates” for a vote during elections. In a report written in the Scroll during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, a politician from Arunachal Pradesh remarked, “Last time, I wanted to contest, so I did a recce … the rate was Rs 20,000 to Rs 25,000 per vote, and there are around 17,000 to 18,000 voters, so adding the cost … it came to around Rs 25 crore to Rs 30 crore. I decided not to contest, it was beyond me.”

Studies conducted by various independent research agencies have shown that the trend of “note for vote” has become extremely common in India and has been on the rise irrespective of the socio-economic status of the recipients. In fact, the earliest evidence of bribing voters goes all the way back to the mid-1950s when parties would offer meals to people and then later request them to vote in their favour.

It is also important to keep in mind that the amounts seized by the ECI, are just a drop in the bucket of the actual amounts of money in circulation during elections. While the election commission places limits on election spending of around Rs. 50-70 lakh for Lok Sabha election candidates, and around Rs. 20-28 lakh for each assembly candidate, the actual expenditures far exceed these limits.

While certainly not all of the expenditure of candidates goes into exchanging cash for votes, it is certainly a significant portion of the expenditure.

Even during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the ECI reported cumulative seizures of cash and freebies amounting to roughly Rs. 5,000 crores, while the overall estimated expenditure during elections was at around Rs. 55,000 crores (Centre for Media Studies). As per data available, 8,024 candidates participated in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Even if we take the upper limit of permitted spending per candidate it adds up to a total expenditure of around Rs. 6,639.22 crores. However, estimates suggest that all candidates themselves spent at least Rs. 24,000 crores in the elections.