Apollo Doubles Its Money in $1 Billion Bet on Tarnished Colleges

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Apollo Global Management Inc. is known for its no-holds-barred dealmaking. But not long ago, the private equity firm pitched itself to pension funds and other wealthy institutions as an emerging force in “impact” investing, the movement to make money while also turning the world into a better place. Exhibit A: higher education.

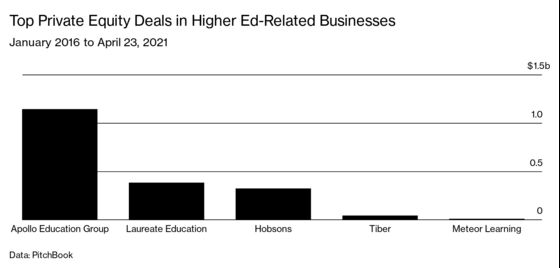

In 2017, Apollo led a $1 billion takeover of the company that owns the University of Phoenix. Before the acquisition, the for-profit college chain “came under fire for aggressive marketing practices and lower-quality degree programs,” Apollo said in a confidential October presentation. But the firm said it was working to transform the school into a “trusted education provider” that helps working adults achieve their dreams. Apollo said this earlier deal showed its social responsibility bona fides as it raised money for its first-ever impact fund.

Fresh complaints from current and former students suggest the transformation—the doing good part—is still a work in progress. But in classic private equity fashion, Apollo has already nailed the doing well part.

The U. of Phoenix’s parent company also owned other schools, including separate programs in Germany, Mexico, and South Africa. The company sold those after the acquisition and is in the process of selling a U.K. school. From these divestments and other payments—including the return of cash the federal government had required the school’s new owners to put on temporary deposit—Apollo expects dividends to its fund that holds the company to soon total $956 million, according to March documents sent to investors. Apollo’s original cost for its stake in the company was $634 million.

And the firm is still the majority owner of a profitable enterprise, which it can one day sell or take public. When all is said and done, Apollo told investors in March, they should expect to almost double the money they invested in the for-profit colleges.

Apollo says it’s already reformed the college’s offerings, and it held off paying itself dividends until the U. of Phoenix was in strong financial shape. Unlike many PE transactions, the acquisition was funded without debt. “This is a great example of how new ownership that is committed to serving students and to providing the necessary capital can combine with new management to change the trajectory of an institution,” says Theo Kwon, an Apollo partner who’s on the education company’s board.

John Sperling, a former San Jose State University professor, founded the University of Phoenix in 1976 to offer an alternative for working adults who needed flexible class schedules. It pushed early into online education and catered to many traditionally underserved students, such as members of minority groups. At its peak the school enrolled almost half a million students. Its business relied almost entirely on federal financial aid.

As a publicly traded company, the school saw its market value soar to $10 billion in 2009. Confusingly, given its current ownership, its parent company was called Apollo Group and then Apollo Education Group Inc. By the time Apollo, the unrelated Wall Street investment firm, came calling, it had only 165,000 students, and its stock had lost about 90% of its value.

Apollo’s partner in the deal was Vistria Group, a Chicago private equity firm. Vistria co-founder Marty Nesbitt is a close friend of former President Barack Obama and chairman of his foundation. Tony Miller, Vistria’s chief operating officer at the time of the deal, was deputy secretary in the U.S. Department of Education under Obama, whose administration led a crackdown on for-profit colleges.

Apollo says it’s put the U. of Phoenix’s bad practices behind it. It cites a drop in student loan default rates, which are better than the national average for for-profit schools and only a bit above the average for all schools. Apollo says the college installed new management, invested more than $600 million in technology to support students, and eliminated 80 associate degree programs, which had poor records for job placement or improving students’ earnings. It cut marketing spending to focus more on student retention, which Apollo says has improved.

There’s reason to be skeptical of buyout funds as stewards of higher ed: Based on data from before the U. of Phoenix sale, a 2020 study by researchers from the University of California at Merced and other schools found private equity ownership led to declining graduation rates and greater levels of student debt at for-profit colleges.

More than 3,000 consumers have complained to the Federal Trade Commission about the U. of Phoenix since the 2017 acquisition, according to data released under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. Their grievances include harassing sales calls and emails, being shortchanged on federal financial aid, and getting pushed to sign up for unnecessary classes. Apollo says many of the complaints are from students who began or completed their studies before the change in ownership. Some complaints are from military personnel and veterans, long a big source of students for the U. of Phoenix. “We haven’t seen anything that would indicate a dramatic change in their behavior,” says Aniela Szymanski, a senior director at Veterans Education Success, a research and advocacy group. “It is kind of disappointing when we speak to veterans.”

Brendon Walker, a 35-year-old U.S. Navy veteran who’s studied on and off with the U. of Phoenix since 2014, doesn’t see improvement, either. He says his online psychology and science bachelor’s program offers little instruction. “It is not a lot of learning,” says Walker, who filed a complaint with the veterans group. “I don’t feel I can use the information.” The U. of Phoenix points to students such as King Imani, who completed his management doctorate in December. The college’s new owners made the school more efficient, says Imani, 31. “The changing technology, the structuring of the staff, everything seems to be more streamlined,” he says.

Apollo says the school doesn’t have an unusual number of complaints for a for-profit college. To monitor sales and other practices, the school has more than 85 compliance workers, and it records calls and reviews them using artificial intelligence. “We have probably been scrutinized more than any other university, and we welcome that,” says Kwon. “This is an area where no corners are cut and we embrace dialogue and focus on quality.”

The Biden administration has indicated it may renew a crackdown on for-profits, and traditional colleges are competing with beefed-up online offerings. It may not matter much for Apollo, given the value it’s already reaped from the deal.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.