A COVID-19 patient arrives at the Trauma Centre of Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS) in Ranchi. (PTI)

A COVID-19 patient arrives at the Trauma Centre of Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS) in Ranchi. (PTI) This pandemic has been a great leveler. Even those hitherto ensconced securely in their panglossian world are now getting to taste the bitter reality as it had always existed for an overwhelming mass of our working people. The world of the haves of India has suddenly collapsed, and all of the king’s men, incapable of putting this world together again, have simply abdicated.

Yet, the suffering that we are condemned to bear ourselves or see around us, still largely concerns metropolitan India. It is important for us to be interested in what might be happening in rural India during the ongoing Covid tsunami, lest the virus capitalises on it for an even more devastating grand staging later.

In generic terms, we all know that the rural health infrastructure in the country is nearly defunct. However, in times when governments are insisting on countering criticism with claims of there being no shortage of beds, oxygen or drugs in the country, prudence demands a closer look at the reality at it stands.

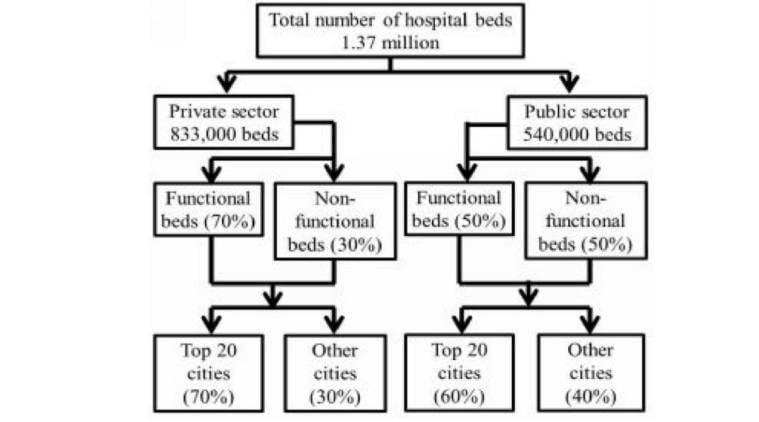

Figure: Distribution of available hospital beds in India

The “High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India”, 2011 figures for the distribution of hospital beds in India (see figure) show that private sector beds far outweigh the public sector hospital beds. Not only is there a deep rural-urban gap in the health services system of the country, but even among urban areas — metropolitan areas draw the maximum advantage. As is evident from the figure, 60 per cent of the government hospital beds and 70 per cent of the private hospital beds were located in just top 20 cities (not even top 20 per cent cities) of the country.

The ‘Human Development Report, 2020’ ranks India 155th out of 167 countries in hospital bed availability. What is interesting is that not only is the overall number of hospital beds in the country way too short, but as many as 50 per cent and 30 per cent of beds in the public and the private sector were non-functional as of 2010. There is a much greater likelihood of such non-functional beds being located in the smaller cities/towns or in rural areas.

The reasons for such skewed distribution is not difficult to understand. The ‘National Health Policy, 2017’, in its draft form acknowledged that “The Government has had an active policy in the last 25 years of building a positive economic climate for the health care industry.” The same document illustrates the consequences: “Indeed in one year alone 2012–13, as per market sources the private health care industry attracted over 2 billion dollars of FDI much of it as venture capital. For International Finance Corporation, the section of the World Bank investing in private sector, the Indian private health care industry is the second highest destination for its global investments in health.”

The bees go where the nectar is; hence the private health sector, especially its most organised form – “corporate hospitals” — set up shop where there is the greatest possibility of making profits, often not just in the richest cities, but the richest areas of the richest cities. Rural areas and the smaller towns are where poverty is most deeply entrenched, jeopardising profits that shall satiate the big sharks in the business of selling healthcare. The “National Health Profile of India” data for the years 2010 and 2019 show that, while public sector beds increased by 30 per cent, those in the private sector increased by 42.3 percent. On a more positive note, though, in these 10 years government beds in rural areas increased by 77.2 percent (from 1,49,690 beds to 3,99,195 beds) and those in urban areas by just 12.4 percent (from 3,99,195 to 4,48,711).

But then, a hospital bed is not just another cot, nor is a hospital storehouse of cots, equipment, drugs and human resource. A hospital becomes capable of providing relief to the people only when it acquires its organised organic form links its various facilities through well-defined processes and is equipped with resources, of which the human resources are the most important.

Among other things, the health services system in India suffers an acute shortage of human resources. Between 2010 and 2019, the Uttar Pradesh increased government rural beds from 15,450 to 39,104 (a jump of 153 per cent), while in same period, the number of physicians in PHCs (Primary Health Centers) and specialists in CHCs (Community Health Centers) in the state declined from a measly 2,001 and 618 respectively to a shameful 1,344 and 192 respectively. If considered so, by the size of its population, UP would be the fifth most populous country in the world with 76.5 per cent rural population. Figures for UP are representative of a scenario shared by many other states. Nothing illustrates the injustice of India’s health services system as does the fact that in 2019, while there were 31,641 government doctors supposedly serving a rural population of 88.4 crore in India, there were 50,173 Indian doctors (23 per cent of all International Medical Graduates) serving total US population of 32.8 crore.

The averments like “having created 18,52,265 Covid beds in total, out of which 4,68,974 beds being in DCH (Dedicated Covid Hospital)” made by the Union government before the Supreme Court in the matter of Suo Motu Writ Petition (Civil) No.3 of 2021, need to be taken in context of the above scenario. Let alone the villages, even in the biggest cities where the health infrastructure is the densest, it has proved to be ineffective in serving people during this crisis.

The the goal of rejuvenating India’s public health system cannot be achieved through a “business-as-usual” approach, whenever the pandemic ends. This is not to say that we need to wait for such a moment. Much of the immediate relief from Covid to rural India can be readily provided by getting fundamental principles right.

People are not dying for want of want of sophisticated interventions, but simply for want of elementary medical advice and drugs meant to alleviate the symptoms, which get escalated in the absence of necessary intervention. They are dying for want of referral transport to get them to the nearest dedicated Covid facility.

Borrowing the words from the December 1948 report of the sub-committee of ‘National Planning Committee’ on ‘National Health’, the need is to place reliance on “Intelligent young men and young women” from rural areas, “able at least to read and write their mother tongue.” Using a “symptom based” approach to diagnosing and treating Covid, they can be trained in large numbers in a matter of days for prescribing symptomatic treatment, in teaching people deep breathing exercises and how to lie in prone position, in providing psychological counselling, and fixing oxygen cylinders soonest the supply chains are established to the block level if not the village level.

Were the Indian rulers to take any cue from their exemplar, the US ruling elite, they shall do well to levy a little more tax on those who made tens of billions of dollars and leapfrogged the international list of billionaires even as the Indian masses bore unparalleled suffering. This would go a long way in raising the much- =needed resources.

The writer is assistant professor, Centre for Social Medicine and Community Health Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.