As We Need to Talk about Kevin turns 10, a look at what made it such a haunting meditation on motherhood

An unshakeable experience and a daring experiment in film form, Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin challenged conventional wisdom on what makes for a good adaptation.

Three days before his 16th birthday, Kevin Khatchadourian (Ezra Miller) kills several students, a teacher and a cafeteria worker in his high school gymnasium. The murder spree began with his father and sister suffering the same fate earlier that day. Left to pick up the pieces is his mother, Eva (Tilda Swinton). The past and present intertwine as Eva recalls Kevin’s formative years from childhood to adolescence, hoping for clues on what went wrong. An unshakeable experience and a daring experiment in film form, Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin challenged conventional wisdom on what makes for a good adaptation. It's been 10 years since its world premiere at Cannes, and we need to talk about what made it such a haunting meditation on motherhood.

The novel by Lionel Shriver relates the story through a series of letters Eva writes to her husband Franklin. Putting herself through a painful process of introspection, she revisits moments from well before Kevin's birth to the eventual tragedy. But Ramsay is less interested in the blame game, more in how trauma can put us in a vicious cycle of self-inflicted pain. She is less interested in the nature vs nurture debate, more in the crippling weight of societal expectations of motherhood.

Though Ramsay does away with Eva as a first-person narrator in the film, she still retains Eva's point-of-view throughout. In Morvern Callar, Samantha Morton grieved her boyfriend's suicide. In You Were Never Really Here, Joaquin Phoenix was a hitman beset by PTSD. The desolate inner worlds of Ramsay's protagonists come alive through a sensory perspective. Haunted by the past, Eva's memories are triggered by sounds, objects and everyday minutiae. Ramsay simulates these associative memories, jumping back and forth between the past and the present. Kids banging on the door on Halloween in the present evokes a memory of young Kevin throwing all his food at the fridge.

The film opens to the sounds of sprinklers tch-tch-ing, before the first shot reveals a half-open patio door whose curtains are wafting with the wind. The camera zooms in, but the scene cuts just before we can get a peek on what's on the other side of it. Mimicking the cyclical nature of trauma, the shot repeats in the climax, where Eva discovers the slain bodies of her husband and daughter. The opening shot fades to white, before cutting to a sea of red in the next sequence, foreshadowing the bloodshed to come. A flashback, from long before Kevin was born, shows Eva at La Tomatina, celebrating with the crowd. In a sonic sleight-of-hand, the joyful cheers alchemise into the sorrowful cries of the families and friends of Kevin's victims.

Ramsay establishes a sense of aloofness in Eva with Kevin still in utero. She frames Eva's discomfort against overjoyed mothers showing off their baby bumps in a pre-natal yoga class. As she leaves, a troupe of tiny ballerinas in tutus run past her. But her expression is one of strained indifference. She's like a fish out of water. Her emotional state doesn’t change even when Kevin is born. She sits in a blank daze in the hospital room. The bed, the gown, and the walls bleed into each other in their cold whiteness, externalising her inner state of mind. Years later, the birth of her daughter Celia, on the other hand, feels more festive. Eva's elation is reflected in the room's warm yellows and flowers on the bedside table.

Eva’s struggle to connect with Kevin only deepens with age. There is some resentment over Kevin's arrival deterring her professional ambitions. Maternal ambivalence turns into filial antagonism, colouring her perception of him as inherently evil. Kevin's insidious nature is best exemplified in a scene staged in the aftermath of Celia losing her eye. While Eva and Franklin argue over the accident, Kevin taunts his mother by peeling a litchi, with a smug look on his face. The sound of him savouring the juicy fruit — a fruit he doesn't even like — in deliberate crunches of sinister delight becomes unsettling when paired with the thought of Celia's lost eye.

The real horror in We Need to Talk About Kevin is society's dogmatic conception of motherhood,

and the pressure to live up to it.

The colour red is a recurring motif in the film. We see it in the wall of canned tomatoes that play backdrop to Eva’s anxiety attack in a supermarket, and the Cabernets she drowns her sorrows with. The red paint of vandals stains her car and the front of her house. Like Lady Macbeth, she tries to scrub the guilt off her hands. Though unlike the Shakespearean character, the question of Eva’s guilt has a lot less cut-and-dried answer.

For mothers always seem to be on trial. In We Need to Talk about Kevin, Eva is literally on trial for parental negligence. The real horror in the movie is society's dogmatic conception of motherhood, and the pressure to live up to it. The real monster is expecting nothing less than unconditional love. Instead, maternal ambivalence is coded as horror. To express concern over a child's habitual malice is coded as monstrous. Being a child somehow means they're inherently innocent. Being a mother somehow means they're inherently guilty. It's why vandals paint Eva’s house in red, and neighbours take out their anger on her. It is so ingrained in our culture even a fellow grieving mother slaps her in the parking lot.

Ramsay builds on Shriver's idea of internalised blame with how Eva sees herself following the tragedy. When Eva dips her whole face in a basin of water, her face turns into Kevin's. When he is interviewed on TV, a reflection of Eva's face on the screen is overlaid on his. Besides their physical likeness, Eva and Kevin also share a certain coldness, which plays into Eva's self-hatred. Swinton said as much in an interview, “It’s about her fears and the horror of what she knows about herself...using him as a kind of projection of her own self-loathing. The most horrendous thing for her to stomach is not that his misanthropy and violence is really exotic and foreign; the thing that is really horrendous is that she recognises it only too well, because it comes from her. He is her.”

Her identity forever defined by the horrors inflicted by her son, Eva’s punishment is her loneliness. Alienated from friends and community, all she has left is her son. Despite his crime, she sells the house to pay the legal fees, moves closer to the prison so she can visit him, and continues to support him. The truth to motherhood is a harsh one. Nicoletta Vallorani in her essay “Of women and children: Bad mothers as rough heroes,” reads a Biblical metaphor into We Need to Talk About Kevin. “The name itself — Eva — is not chosen by chance, echoing the fatally disobedient woman of the Bible, whose act determined the loss of the Garden of Eden. Eve disobeyed, she ate the apple and she was punished by becoming not only human but also a mother. Motherhood was therefore intended as a punishment.”

Eva was never allergic to being a mother of course. We see it in her bond with the more amiable Celia. Her only crime was perhaps hurrying into the role before she was ready. In Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood, Sarah Arnold identifies how mothers as characters suffer from a Manichean oversimplification, or as she calls it the “unstable ideology of idealised motherhood”. There's the Good Mother, like Diane Freeling who travels to another dimension to save her daughter in Poltergeist. The Bad Mother refers to oppressive puritans like Margaret White in Carrie. But recent years have shown horror films can write mothers full of contradictions that challenge the status quo. Annie Graham in Hereditary is conflicted by feelings of love and hate, resentment and remorse, towards her son. So is Amelia in The Babadook. And so is Eva. Ramsay improves on Shriver's portrait of a mother with an honesty that leaves us thinking about Eva long after the credits roll. Each rewatch only feels more rewarding because Ramsay is so pure and gifted a filmmaker she rattles and revises our preconceptions of what a movie — and yes, mother too — can be.

also read

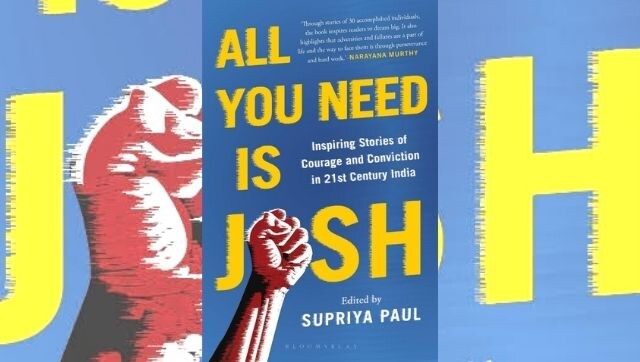

Read an excerpt from All You Need is Josh: An anthology of stories of courage and passion in modern India

Supriya Paul's book builds on the work she is engaged in as part of Josh Talks, a platform striving towards bringing to the fore stories of great courage and strength from all corners of the country.

Workers Leaving the Factory: How Louis Lumière’s 1895 film bound labour and cinema together for eternity

Traditionally considered the first ever motion picture, its image of workers leaving the factory was a veritable birthmark for the medium.

At Visions du Réel 2021, two films explore the intersection between images and war with great cogency and rigour

Directed by Massimo D'Anolfi and Martina Parenti, the Italian feature War and Peace and Bellum — The Daemon of War, made by David Herdies and Georg Götmark, illuminate the profound, multi-layered links between war, photography and cinema.