Meagre wages for Kashmiri Pashmina artisans, rise of machines push ancient handicraft to edge of extinction

Before India’s economic liberalisation in 1991, the traditional yinder gave women of Kashmir economic independence. It was in almost every household

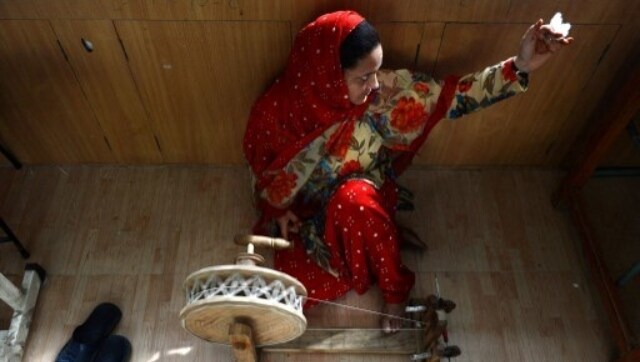

A file photo of a Kashmiri woman working a spinning yarn of Pashmina. AFP

Women in Kashmir have been using yinder (traditional spinning wheel) for centuries to produce pashmina fibre. Yinder has a high traditional and cultural importance in Kashmir. Its possession in households is still considered a blessing. The craft of making Pashmina shawls was introduced in Kashmir by the 15th Century ruler Zayn-ul-Abideen who brought highly-skilled craftsmen from Persia.

Later, locals learned the craft and it began to flourish. During Mughal rule, the Pashmina shawls became famous in Europe, and the shawl has become a statement of high fashion across the world ever since.

In Srinagar’s Eidgah, sitting on the verandah of her kitchen, Mehmooda Bano gets nostalgic as she winnows rice and lentils. She recalls the time when she would spin yinder to make delicate pashmina fibre. Three years ago, she sold her yinder for Rs 900 to a neighbour.

“My husband is on medication. He sleeps almost all day and goes to work only when he pleases. I needed money to pay my son’s school fees. I had already collected some money and was a bit short. So, I sold my yinder because it was lying useless for a long time.” said Mehmooda.

Other women in the Valley tell similar stories. Neelofar, 52, a houswife, said, “I initially gave it to a middleman who turned around and sold to a very poor woman. When I saw her condition, my conscience didn’t allow me to take money. So, I gave it the money to her.”

Neelofar said she left the trade due to deteriorating health. In order to spin, she had to sit in a crouched position for hours. When she began to develop a problem with her eyesight and pain in her spinal cord, she called it quits.

“There was a sort of blessing in the money we earned from it. We could buy so many things with it,” said Neelofar’s sister-in-law Saira.

“And best of all, it was all our own money. We didn’t need anyone’s permission to spend it. But now it is not like that. Even after one month, you would be paid peanuts. That’s why my yinder is lying in the attic, I have not touched it from years,” added the 58-year-old.

The raw pashmina for spinning comes from Ladakh which is then spun by Kashmir’s women spinners who extract the rough particles from it and turn it into fine and soft threads. By the time the Pashmina shawl, known for its elegance, reaches the hands of a customer, the final product passes through 24 stages of manual work.

The pashmina fibre is very delicate and cannot withstand the force of a spinning machine so it has to be individually handspun on a traditional wheel and then meticulously dyed and woven.

The birth of the machines and death of a craft

Before India’s economic liberalisation in 1991, the traditional yinder gave womenfolk of Kashmir some economic independence. It was in almost every household. But for the past decade and a half, as industries began to set up in Kashmir, the craft has been hijacked.

Now, it can be seen only in the hands of widows and the poor.

According to the Department of Handloom, 1 lakh women were registered as spinners in 2007, and unofficially, around five lakh women worked in their homes. However, in 2021, there are only 15,360 active women spinners registered with the department.

The Economic Survey of 2018, published by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics states: “The handloom sector is facing multifaceted challenges primarily due to machine-made fabric and trade liberalisation. Poor productivity of weavers, increased cost of production of handloom cloth, cheaper and quality synthetic substitutes in the textile sector, and changing consumer tastes have put a serious constraint in the development of this sector.”

Under the 1985 Handloom Protection Act, processing any kind of pashmina thread in industrial factories is banned. However, with the government failing to implement it, the law remains only on paper.

“In 2019, the district commissioner issued a blanket ban on any pashmina to be processed in industries. But the problem is that there is no enforcing agency” says Dr Nargis, joint director at handlooms department, “It is evident that with the advent of industries and power looms, the women lost their work, and all the traditional acts began to go extinct”

“There have been no schemes from the government which aim to rehabilitate these women. We have spinning centres for women where we teach them how to make the fine thread on the wheel but for rehabilitation, there is no such scheme.”

Meagre wages

Apart from the threat of mechanisation, another challenge is the low wages. The powerloom owners, operating illegally, mix nylon, viscose and other harmful chemicals to make it strong enough to spin pashmina yarn on machines. As a result, almost 9 lakh women associated with the craft have been rendered jobless.

The Pashmina shawls produced on power looms cannot be classified as authentic pashmina, but are branded as 100% handmade and sold in the national and international markets, which is damaging the reputation of the ancient and reputed craft.

The cost of making a pashmina on a machine is 1/4th of a pashmina made by hand. As a result, the people associated with this craft began leaving in droves.

“Fifteen years ago, I could buy clothes for my children with money I earned. But even if they give me Rs 10 per knot now, I still wouldn't do that work. Wages are still low. ” says Neelofa

Abrar Khan, chairman, Genuine Kashmir Cottage Handicraft Protection Forum, has been fighting to get minimum wages act passed for the women spinners. His organisation conducted an economic survey of the artisans related to the pashmina craft.

“We got shocking results. The per capita income of the women spinners is Rs 700 per month, which is not even a fraction of the national index. Our women who would spin charkha have left it. The reason is that they get the same wages that they did 20 years ago. It’s still one rupee per knot. I don’t think anyone will do so much hard work for just 500 rupees.”

“Take the women who spin, for example. If they are given 100 gms of pashmina to spin, considering the wastage, it comes down to only 85 gms. But she gets wages for 85 gms while she processed 100 gms. She loses 15 percent of her labour just because of what she was provided by her consignee. They are being robbed of their wages. This is a skilled labour job, and at least the spinners should get the minimum wage. We demand that the artisans should be under the wages guarantee act and in the skilled labour category,” said Khan.

Khan believes the elite, who run the show, survive on the exploitation of artisans who number around 9 lakh.

“There is a stratum of people who are basically the middlemen between the artisans and the customer. An artisan works hard to make a Pashmina shawl and then the middlemen who have customers in Europe and North America make an unimaginable profit. And what are the artisans paid? Not even 1/4th of the retail price. Even their own wages are paid sporadically. Whenever the contractor is in the mood, he pays. If he has fought with his wife, then he doesn’t. During 2017-2018, handicrafts goods worth Rs 1,090 crores were exported. Where is that money? It’s all with the rich people who own big companies. And artisans are pushed to the brink of starvation.”

“Compared to ten or twenty years ago, economic conditions are better now in general. More women are being educated,” said Dr Nargis, “Rather than spinning pashmina, young girls want to become teachers or work at an office. Women have left the craft mainly because the wages have not kept pace. Unfortunately, it is not up to the handlooms department to raise wages. Wages are under purview of the labour department. And, sadly, spinning women have not been classified under skilled workers, nor have they been registered under the labour department so that their wages increase. Apart from that, the middlemen who provide the raw material, it seems, do not have the empathy to pay them more.”

But Khan believes that the main problem among the government departments is the ownership crisis. "When there is a new scheme and money comes from the government, everyone steps forward. But when you have to own the losses or implement policies on the ground, handicrafts department passes the buck it to handloom department and handloom department pushes it to the labour department,” Khan said.

The certificate of originality no one knows about

In 2008, the Government of India successfully secured the Geographical Indication Mark, an intellectual property right, from the World Trade Organisation to ensure that Kashmiri artisans have exclusive rights over the Kashmir Pashmina brand. GI Mark is conferred upon certain products that correspond to a specific location. The Craft Development Institute issues the labels on the pashmina products after testing it in their laboratory.

The labels are equipped with Radio Frequency Identification Tag (RFID) which stores and transmits details as digital data of any pashmina product. But despite the government’s efforts, very little has changed on the ground. Customers have not been educated about the product.

“Where we lose is in the marketing.” said Khan. “The GI shawls produced by the artisans are 100% handmade. No machine is involved in the process of making shawls which are GI labelled and we need to promote that. Only the elite attend big exhibitions. We need to advertise authentic pashmina and educate the customer of the difference between machine-made and handmade.”

Khan said the government has already made some changes, but a lot more needs to be done with regards to marketing. “As of now, there are only talks from the government. There's no change on the ground,” Khan stated.

also read

JKCET 2021 exam: Online registration for CET extended till 10 May; visit jkbopee.gov.in to apply

The application form will only be considered complete when it is filled completely, payment is done correctly and relevant documents are uploaded to the official website

J&K HC directs admin to appoint nodal officers to ensure oxygen supply for COVID patients at home

The court asked the health secretary of the Union Territory to come out on affidavit within two weeks giving a detailed report

Three militants killed in encounter with security forces in Jammu and Kashmir’s Shopian; one surrenders

The encounter began after information about the presence of new recruits of the Al-Badr outfit emerged crept in