Updated: May 9, 2021 8:53:47 am

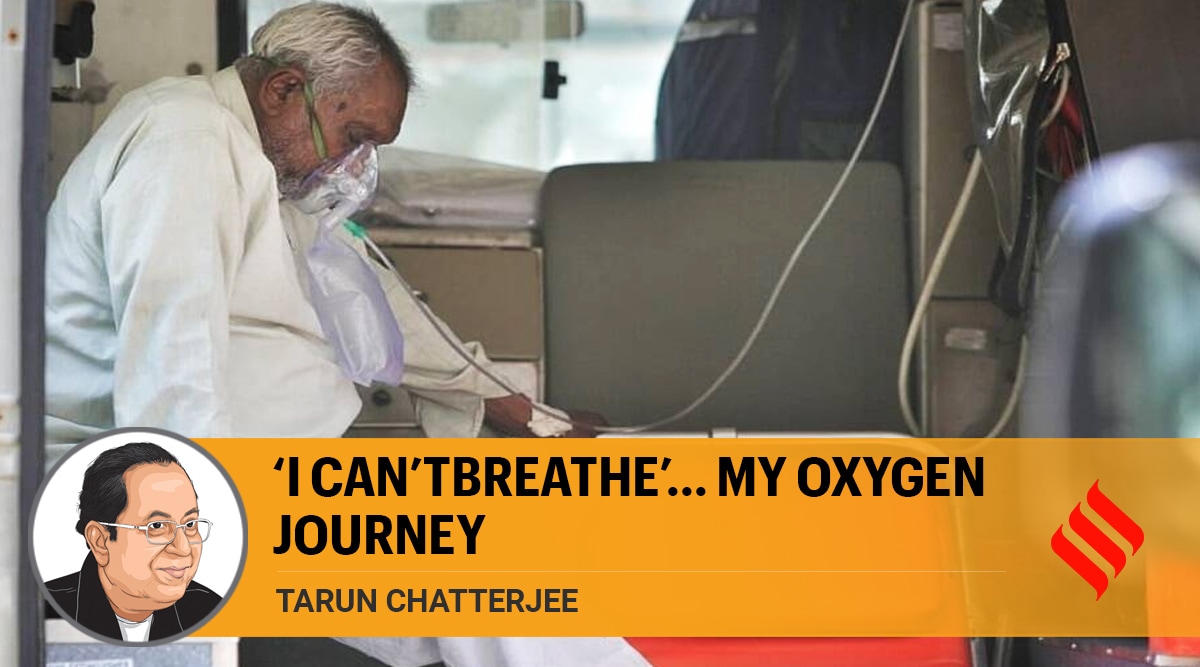

Covid patient with oxygen support waits for hours to get admission at a 600-bed Covid ward at Civil hospital in Gandhinagar. (Express Photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Covid patient with oxygen support waits for hours to get admission at a 600-bed Covid ward at Civil hospital in Gandhinagar. (Express Photo by Nirmal Harindran) Written by Tarun Chatterjee

At my primary school in picturesque Chakradharpur (part of Bihar earlier and now in Jharkhand), our headmistress Gita Sarkar, the granddaughter of noted historian Sir Jadunath Sarkar, would say, “Boys and girls, take care of the trees as they give us oxygen.” With suspicion in my mind, I would watch the trees at night from the window and fail to see such action.

My uncle was a mining contractor and he used liquid oxygen in cylinders. Before sending the cylinder for refilling, he would release the leftover liquid in the open ground in front of our house and this would create a magical landscape of thick white clouds reminding us of the dream sequence of Raj Kapoor’s movie Awara.

During my first chemistry class in secondary school, Nimai Sir would say, “The other name of water is H2O… two hydrogen molecules combining with one oxygen make water.”

Later, during my chemical engineering days at Jadavpur University, Professor Roychaudhury would say, “Oxygen is used to make steel in LD process, other industries and in hospitals to treat critical patients.”

During my service life at Bhilai, I discovered steel plants are a jungle of wild technologies. In the coke ovens, oxygen is forbidden and the whole chemical process must be done strictly in absence of oxygen since the gas can cause big explosions.

On a night shift during a routine inspection, I would fall unconscious in the underground coke oven’s battery cellar, and would find myself in the hospital bed the next day, breathing through an oxygen cylinder.

I would not show any respect for oxygen then, and throughout my service life would continue to work on technology that forbids the presence of oxygen. This would continue, till one midnight, on June 3, 2020, when my wife Maya would say, “I can’t breathe”.

Within minutes, the security persons would come with a wheelchair and I would take her to the basement where Padmanavan, a fellow resident, would be ready with his car and take us to the emergency wing of Manipal Hospital. It was peak of the first Covid-19 wave. My daughter Julie and Sumit reach the hospital, and after half an hour the doctor says, “Her oxygen level has come down to 40% and we have started giving her oxygen….”

Even after this, I would ignore oxygen. But only till April this year, when the BBC would present a very grim picture of the oxygen crisis in India, including the incident of the oxygen leak at a Nashik hospital. I would spend a sleepless night and next morning would go through publications of the WHO, World Bank, Johns Hopkins etc.

The concept of modular captive oxygen units for medical use was first promoted by the US military during the Gulf War in 1970. Prior to that, oxygen was made by cryogenic distillation of air and transported in tankers. By mid-June 2020, the Centre had sanctioned 160 such modular units for hospitals, but even as I write this piece, order for only 33 units has been placed.

Insensitive bureaucratic systems and power lobbies diluted the national priority. Kerala showed outstanding vision and courage by engaging the 123-year-old government firm PESO (Petroleum & Explosives Safety Organisation) as the single decision-making and implementation body. Subsequently, through crowd-funding projects, many hospitals implemented copper pipe supply system for oxygen. Hospitals in Kerala are now self-sufficient in oxygen and export it to neighbouring states. But, “I can’t breathe”, the last words of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, are echoing in many hospitals in India today.

The Bengaluru-based writer is a chemical engineer who has worked with various PSU steel plants

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.