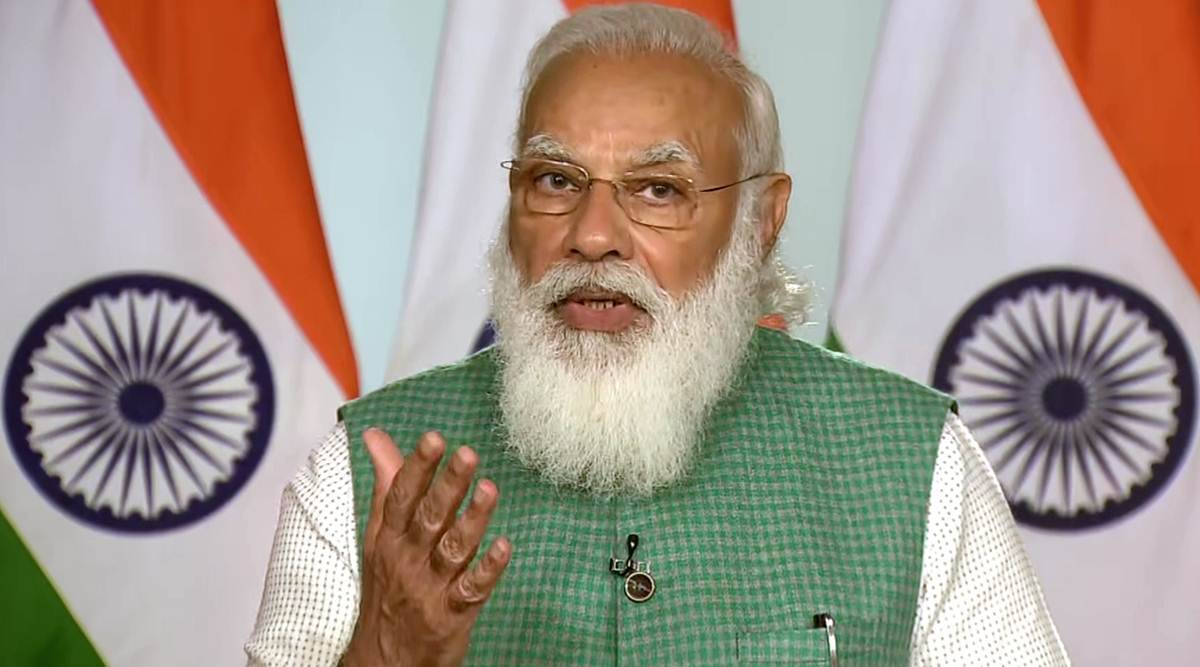

PM Narendra Modi (File photo)

PM Narendra Modi (File photo) As death and suffering knock on each of our doors, our politics requires a temporary injection of idealism. In a political landscape marked by communalism, polarisation, petulance, authoritarianism, aggression, any call for idealism will invite the response “What are you smoking?” But the blunt truth is this: If our politics continues as usual over the next few months, the devastation to our lives will be immeasurable. Covid is exploiting every social faultline, worming away in glee, as we turn on each other more than we unite against the virus.

There is palpable and justifiable anger against the sheer callousness and incompetence on what the central government under the leadership of the prime minister has inflicted upon us. But the political hard truth is that national elections are three years away. As much as I might want one, an immediate change in government is not our quick or easy road to redemption. Despite waning popularity, the hardcore supporters of the BJP are still dug in. They are not a majority but still a sizeable number. Their response to criticism has been to double down with even more aggression. On the flip side, the BJP must recognise that no fight against Covid can now work without the cooperation of every political party. This is partly because the Opposition controls key states. But it is also because if the fight about Covid becomes a fight over petulant one-upmanship as we are, for example, seeing between Delhi Government and the Centre, then we are doomed.

It is a cliché that it would be ideal to “depoliticise” the fight against Covid. One has to be careful about how the term “depoliticised” is used. It should not be used as an excuse to silence criticism, or demands for accountability, or public expressions of anger. These are necessary tools in crafting a better response to crisis. If nothing else, they provide information and create pressure. “Depoliticised” simply means creating structures of decision-making where the incentives to cooperate are strengthened and achieving results becomes more important than embarrassing opponents; a tangible verification of results becomes more important than perception management. In times of war and foreign policy crisis, such bipartisanship is not unusual. There is reason to deploy it in the context of one of India’s most significant crises since Independence.

So here might be some simple objectives that could allow some semblance of unity, public purpose and resolve in the fight against Covid. The first is the creation of something like a national action plan for the next two to three years, with tangible and realistic targets on everything from vaccination procurement and pricing, to preparedness for future waves. The important thing is that the plan must be made and owned by all the state chief ministers and the central government together. So that the national strategy is, as far as possible, a consensus document. This document must also take hard decisions about financial allocations and building up the public health infrastructure.

The second is a recognition that in the short to medium run there will be considerable scarcity and rationing, from vaccines to other supplies. It is important that the rationing be done fairly, according to principles that make sense from a public health point of view. The more such rationing decisions are collective decisions, the more confidence in their fairness. In times of scarcity, you also need coordination and trust to adapt as situations change.

The third is the activation of parliamentary select committees as tools of accountability. This is not a time to suspend parliamentary activity, but deploy it in ways that produce accountability through formal channels. The very fact that the bureaucracy or the scientific establishment can be asked tough questions by members of different political parties may change the incentives on how information is put out. Allowing a parliamentary committee to ask why the ICMR was so slow in sharing data, for example, is not a bad thing; and the fact that they know they are now answering only to the executive will increase confidence in the system. We know parliamentary committees have, outside the glare of politics, done a better job of flagging so many issues.

Fourth, for the time being, depoliticise the bureaucracy. Again, the fact that bureaucrats will be answerable to different CMs and parliament, rather than serve one master, will help in this. The insidious practice of bureaucrats now having to be like public spokespersons for the central government has destroyed the credibility of the bureaucracy but also made interstate coordination more difficult. Fifth, it would help if, for the time being at least, there was a commitment to prioritising the pandemic. I don’t mean that in just an administrative sense. Frontline workers are battling this crisis. I also mean in a psychological and political sense, where we can convey that the death and suffering around us is not just an afterthought tacked on to the usual pathologies of politics. This will require an almost heroic forbearance. The usual ingredients of politics — communalism, ambition, venality — will still be around for parties to play with when this is over. The point is to demonstrate that the different sinews of power are pulling in one direction, at least on the pandemic.

It is remarkable that even the United States, which used to be recalcitrant on granting IPR waivers, is seriously moving in that direction. When it comes to Covid, globally, there is a recognition that we need to move from nationalism to treating Covid as a global public health issue. It will be ironic if the world moves in that direction, but India internally remains trapped in a competitive acrimonious free for all, as if Covid was another pretext to fight. No part of India can win unless the whole of India wins. Vasudhaiva kutumbakam for the world, but Matsya Nyaya at home, where the bigger fish eats the smaller fish, is not exactly a coherent moral outlook.

I know this hope for coming together rather than falling apart on the pandemic is a forlorn hope; but the alternative is worse. The initiative for a temporary reconciliation will have to come from the Prime Minister. This can be his opportunity to do the right thing. But the Opposition also has an interest in India succeeding on the pandemic. It also knows that it is hard to predict what the tides of death, destruction and distress will sweep up in their wake.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.