New Species of 'Duck-Billed' Dinosaur Discovered in Japan

They may be some of the planet's most ancient creatures, but there's a whole lot about dinosaurs that we have yet to uncover.

Researchers, however, are making new discoveries about these mysterious beasts all the time. The announcement of a previously unknown dinosaur species earlier this week is bringing some new clarity to a beloved topic.

According to Science Daily, the creature's fossilized remains were reportedly first found in 2004 by an amateur fossil hunter on Awaji Island, a southern island of Japan. The discovery included the dino's lower jaw, teeth, neck vertebrae, shoulder bone, and tail vertebra—all captured in sediment dating back about 72-million years.

The fossils were handed over to Japan's Museum of Nature and Human Activities and were studied by scientists and researchers in the years since.

Now, they've identified the creature as being part of an entirely new species and genus of hadrosaur. The new dino's official name is Yamatosaurus izanagii.

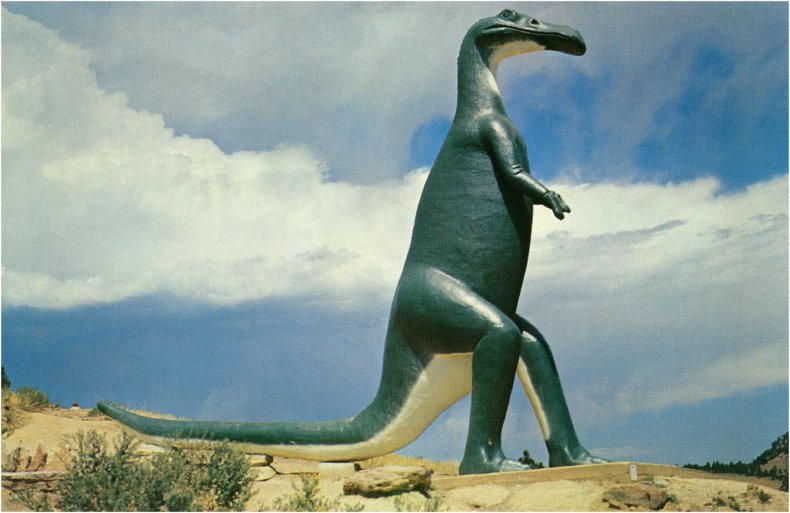

Science Daily says that hadrosaurs "are the most commonly found of all dinosaurs" and are "known for their broad, flattened snouts" which resemble ducks' bills. They were herbivorous creatures who lived over 65 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous period. Hadrosaur fossils have been found all over the globe, in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia.

The discovery of the Yamatosaurus, however, introduces some changes to researchers' previous understandings of hadrosaurs. Specifically, the "dental structure" of Yamatosaurus is distinct from that of other hadrosaurs, suggesting that these creatures had different diets.

While most hadrosaurs have "hundreds of closely spaced teeth in their cheeks," the new species "has just one functional tooth in several battery positions and no branched ridges on the chewing surfaces, suggesting that it evolved to devour different types of vegetation than other hadrosaurs."

The species also provides new information about dinosaurs' evolution and migration patterns. The Yamatosaurus is distinct in "the development of its shoulder and forelimbs" which illustrates an important "evolutionary step" as hadrosaurs transitioned from walking on two feet to all-fours.

Additionally, the new species raises questions about hadrosaurs' migration patterns, potentially "suggesting that the herbivores migrated from Asia to North America instead of vice versa."

"In the far north, where much of our work occurs, hadrosaurs are known as the caribou of the Cretaceous," said Anthony R. Fiorillo, a senior fellow at Southern Methodist University's Institute for the Study of Earth and Man. Hopefully, the discovery will lead to further research of Yamatosaurus and hadrosaurs in the area.