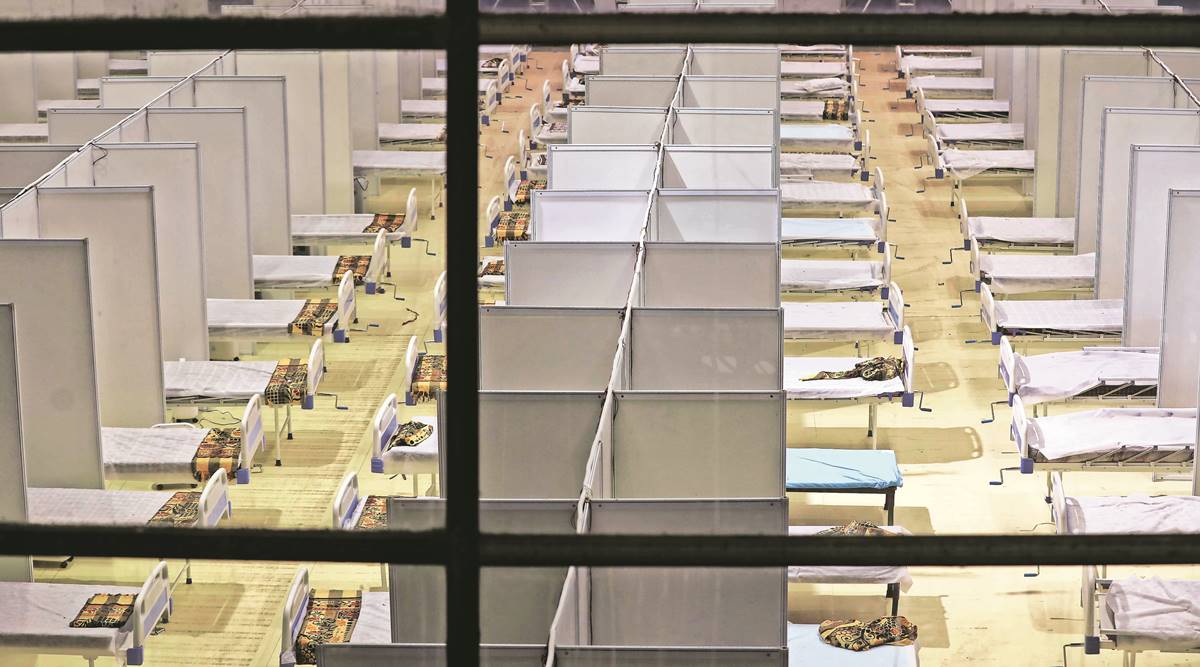

At the Covid care centre at CWG village near Akshardham on Tuesday. When a person tests positive, depending on the severity of the disease, they are assigned hospitalisation or home isolation. (Express Photo by Abhinav Saha)

At the Covid care centre at CWG village near Akshardham on Tuesday. When a person tests positive, depending on the severity of the disease, they are assigned hospitalisation or home isolation. (Express Photo by Abhinav Saha) Delayed test results, no call from authorities for days, and a healthcare system bursting at the seams — these are key causes for the near collapse of Delhi’s triage and home isolation system, reflected in many people taking sick relatives from hospital to hospital without direction from authorities.

Like most other cities, guided by the Centre’s policies, Delhi notified the procedure to categorise and treat Covid patients in April, 2020.

When a person tests positive, depending on the severity and other key factors, they are assigned hospitalisation or home isolation. For those in home isolation, a district-level team is supposed to stay in touch every day to check up on them and help shift them to a hospital if their condition deteriorates. If a person needs hospitalisation, they are asked to call an ambulance on 102, which, based on the district medical officer’s guidance, has to take them to a hospital.

But given the deluge of cases, the system is barely functional anymore.

The Indian Express spoke to seven patients who tested positive in April, some in the beginning of the month and some last week. Only one had got a call from the district officer, who promised that a doctor would call her every day. In this case too, no call came.

Of the others, a 34-year-old man tested positive in early April and when his condition worsened, his wife, who also had Covid, had to make several calls to hospitals to get him an oxygen bed. Even this was managed because her father had worked in a private hospital earlier and he had to plead with the authorities. They did not get calls or medicines from the government, which is supposed to be the first step of the home isolation process.

Three of the seven have recovered without a single call from the government.

‘Lack of anticipation’

“The protocol remains the same still. It is just that when you have 25,000 cases in a day, the system gets overwhelmed. It is not like the capacity could not have been upped; just that not one thought in that direction. At the first step, test reports are delayed, which means that by the time the office of the district medical officer gets details of the patient, they are already in the third or fourth day of the disease. Second is that because there are so many calls to make, contact with the patient or their family gets delayed further. And third, even if we have established contact and sent an ambulance to the patient’s house, there are no beds available,” said a Chief District Medical Officer.

“These systems were made to work, but never revisited to make sure we have the capacity to deal with this case load,” he added.

According to data provided by the Delhi government, it received 990 calls on the control room numbers on Monday and 2,434 calls were dispatched to ambulances. But the lack of beds and the Delhi corona app being unreliable at times means the ambulance driver is forced to drive patients from one hospital to another. A few get lucky, some have to return home, while some die on the way.

A Delhi government official said it was worrisome that many patients were not getting calls from the district offices. “The system is overwhelmed, but this should not be happening,” the officer said.

Meanwhile in Mumbai

Mumbai has on the other hand built 24 war rooms to triage patients. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) receives 8,000 calls on an average every day in the war rooms and its umbrella helpline number 1916 that is managed by a disaster management cell. The war room operates 24 hours in three shifts with municipal school teachers, doctors, engineers and officials from the health department handling a slew of queries — on beds, ambulances and testing.

Dr Mangala Gomare, executive health officer, said, “Mostly for one patient, at least two to three calls will come from different family members. In most cases our war room responds. Of course there is always scope of improvement.”

The laboratories are supposed to inform BMC about positive reports, twice daily — once at midnight and once early morning. Only after that can a lab report convey the test results to the patient. The war room prepares a ‘line-list’ and calls are made every morning to newly infected people — by current trend that means calling 7,000-8,000 people a day.

Since most of the staff in the war room are not from the medical field, they have basic training to ask for symptoms, oxygen level, comorbidity, age and then ’triage’ the patient into whether they need hospitalisation, institutional isolation or home isolation.

The war room has a live dashboard of every Covid hospital in the city, its available oxygen beds, ICU beds and ventilators. The war room informs the hospital that they will soon be sending a patient. It fixes an ambulance (mostly private vehicles converted into makeshift ambulances hired by BMC) and tells the patient to get ready. Hospitals have clear instructions to not admit a patient, unless an emergency case, without coordinating with the war room.

The only glitch currently is dearth of ICUs and ventilators. As on Sunday, BMC had no ventilator and only over a dozen ICUs to spare. The war room had no option but to ask patients to wait. A doctor at a jumbo centre said most admissions happen through war room referrals, except for emergency cases.

Recently, the BMC has also started sending a team of health officials to homes of patients to verify if they require ICU admission. This move came after panicked patients started demanding an ICU bed over call.

With inputs from Tabassum Barnagarwala

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.