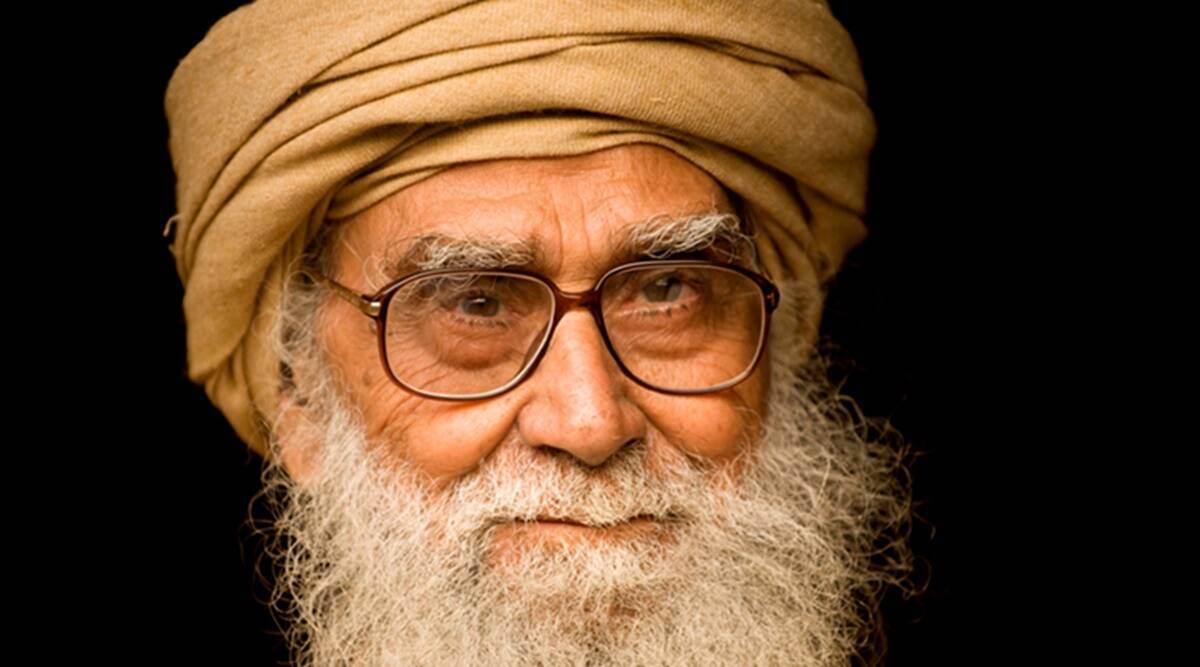

Maulana Wahiduddin Khan (file photo)

Maulana Wahiduddin Khan (file photo) Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, who passed away on April 21, belonged to the age of slow and careful work on the inner self. This made him a powerful inspiration, inviting one to step away from the frenetic bustle of political conflicts and instead reflect on unchanging truths.

I first met him in January 1993 when Maulana saheb joined a diverse group of about 30 people, for an unusual four-day meeting at an ashram in Vrindavan. This meeting was a dialogue between activists of the RSS and activists of the Gandhi, Lohia, Jayaprakash Narayan tradition.

The gathering had first been planned in mid-1992. At that point, some senior activists of the Left parties and grassroots groups had also agreed to attend. For many this attempt at a dialogue was aimed at diffusing or solving the conflict over the Babri Masjid.

After the demolition in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992, many from the Left-liberal tradition decided not to attend the dialogue in Vrindavan. Maulana saheb kept his promise and came to the meeting. His commitment to listening and attempting a dialogue was not constrained by circumstances — even one as dramatic and decisive as the event in Ayodhya.

At that point, three decades ago, I must confess my faith in dialogue was rather fragile. I attended this meeting largely because it was co-hosted by my friend and Lokayan colleague, Vijay Pratap. When friends and comrades take an ambitious and bold step, the very least one can do is to support by being present.

For four days this group made up of political opposites, met for long hours. We would sit on floor cushions in a square formation. We may not have made great strides towards a heart-to-heart conversation. But it is fair to say that neither side just talked “at” the other.

The RSS activists, including Govindacharya, gave an intricate account of the reasoning that drives their politics. In response, many of “us” questioned that reasoning and put forth our anxieties. The common ground was love of India as home, as our unique place in the world. The crucial and painful difference between the two sides was about how the logic of violence plays out. What “we” saw as the wanton spreading of hate, “they” saw as a minor side effect in a larger transformative exercise for India to find its feet.

Through all this and much more Maulana saheb remained at peace. When he spoke, it was to express his truth with a quiet and calm confidence. There was not a trace of contentiousness or any emotions, any words, that would add to an atmosphere of conflict.

For he truly believed that the conflict was illusory. It seemed to me that he was reiterating an old truth, one that Mahatma Gandhi had tirelessly repeated as well. That if each one of us could just be a true Hindu or true Muslim, there was nothing to quarrel over.

Even as the meeting in Vrindavan proceeded, Mumbai, my home town, was burning as communal violence raged across it. In the midst of such tragic and frightening news, how was Maulana saheb so calm, so peaceful?

For me, this question became for more important than our discussions with the RSS activists, which often seemed to go round and round in circles.

So, on the last day, as we all prepared to leave the ashram, I respectfully asked Maulana saheb to share his secret with me.

As far as I can recall, my voice broke even as I posed the question to him. What enables you to be so much at peace?

He became quiet and reflective. Then, in a soft and slow voice, he said: “Zindagi mein toofan to aate rahate hain. Humein use chidiya ki tarhan hona chahiye jo toofan ke badlon ke oopar udna seekh le.” To translate: “There will always be storms in life. We have to strive to be like the bird that learns to fly above the storm clouds.”

In the years that followed, his words became a talisman for me.

Eight or nine years later, I had another opportunity to meet him — in Mumbai, when he came to receive the Diwaliben Mehta Award.

I reminded him of our meeting in Vrindavan and expressed my deep gratitude for the beautiful gift of the wisdom he had shared.

He looked at me with a piercing stoic gaze and posed a question in just one word: “So?”

“So, I am not yet able to fly above the clouds but I am striving — mein lagi hooi hoon!” I replied hesitantly.

Suddenly, his face became animated with a mixture of amusement and indulgence. “Tumhein samaj hi nahin aya.” You didn’t really get it, Maulana sahab said.

“Jo lag gaya, vohi ban gaya” — to strive to be like that bird is to be it.

A life such as his can only be celebrated.

Bakshi is the author of Bapu Kuti among other books and the founder of “Ahimsa Conversations” an online platform.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.