Political parties can't be taken to court for breaking their election promises but maybe it's time for a change, writes Omphemetse Sibanda.

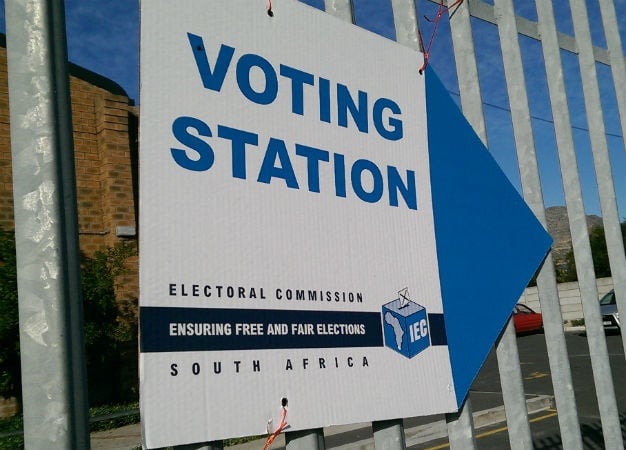

Come 27 October 2021, the local government elections will be in full swing as voters elect, for the sixth time in democratic South Africa, the next cohort of leadership and public representatives at metropolitan, district and local levels.

"The president urges eligible – and especially first-time voters – to ensure they are registered to participate in the elections, which provide the basis for development and service delivery closest to where citizens live," the Presidency said in a statement.

Not everyone welcomed President Cyril Ramaphosa's announcement on the date for the local government elections though.

There have been calls by some opposition parties for the postponement of the elections.

EFF's concerns

The EFF raised concerns that most political parties would be disadvantaged because of a lack of preparation and campaigning due to lockdown restrictions on gatherings.

By now, we know what all parties mean when they say that there were no adequate preparations and campaigning to lure voters. These sharp-tongued politicians mean that they need more time to make promises – which, so far, they have largely failed to keep. Promises of water and sanitation; promises of free education; promises of adequate shelter and housing; promises of employment opportunities and a living wage. The list of promises is endless.

Since this is about local government elections, I would like to contextualise my opinion by using the example of my community of Letsopa, in Ottosdal. If you do not know where Letsopa is, it is a township alongside Ottosdal in the North West.

Letsopa is one of the shameful experiments of local government in the democratic dispensation. Communities are still not able to access consistently running water more than 25 years into democracy.

The ANC's 2019 manifesto slogan "Let's grow South Africa. Together" could have made an excellent overarching promise for all parties contesting because they all claim they can give South Africans a better life. But what life can be better without water in Letsopa, for instance? Nothing!

On arrival in the township, you'll be welcomed by a stream of dirty water running down the street in an area called Meloreng. The name is loosely translated in English to "place of ashes" because it started as a corrugated iron residential area built on the dumping ground where rubbish was thrown and burnt. But, that is not water for consumption. It is sewage water that smells like human excrement. The indignity of the sewage that is allowed to run at the doorsteps of residents is not confined to Letsopa. It is a common sight across many local municipalities in the country.

Manifestos

Now that we know local government elections will take place on 27 October this year, political scavengers for votes will be out in full force, promising voters heaven and earth. This time, both media and concerned citizens must ask hard questions about pledges that prominent political parties make.

We must make a fuss about the manifestos and promises they make.

If you are asking what the fuss is about, the answer is simple. It is found via the three key functions of an election manifesto, namely:

- to provide an anthology of valid party positions designed to establish or re-establish supremacy over its previous and other parties' policy positions;

- to serve as a comprehensive summary of valid party positions intended to serve manifold purposes, such as providing the media with input for their reporting; and

- to serve as a document that enlightens voters on how their party sees the real world compared to other parties.

In 2019, for example, we were bombarded with the following promises: "South Africa deserves a better government" (Congress of the People); "Together we move South Africa forward" (ANC); "Together for change – together for jobs" (DA); "Your hope for a great future" (ACDP); "Now is the time for economic freedom" ( EFF).

Have the ACDP, Cope, DA, EFF, ANC and other parties made good on their promises, or has it been all about the interests of top political party leaders and their cronies?

Nikolaus Eder, Marcelo Jenny and Wolfgang C. Müller, in their article Manifesto functions: How the party candidates view and use their party's central policy document (Volume 45, Electoral Studies 2017, p.74), provide emphasis on the importance of these manifestos.

"Parties … fight elections rallying behind a manifesto, laying down policy priorities and positions, and a team of leaders committed to them. In the subsequent election, voters will not only judge parties according to their policy programmes for the next term in office but also retrospectively, focusing on the government's performance and scrutinising if the parties have kept their promises," they write.

I am more fascinated with the issue of keeping commitments and judging the parties, which is something we must do starting with the local government elections. Otherwise, we must forever hold our peace if the political parties cannot keep their word and we still vote them into the coalface of service delivery – local government.

Unfortunately, political parties cannot be taken to court for breaking their election promises.

They pledge and promise but are hardly made to account, except during the next election when voters have an option to vote for the status quo or a change of government.

Not legally binding

In South Africa, a party election manifesto is not legally binding to be enforceable. There are few judicial options to have recourse to foster compliance with election manifesto promises.

The subject of enforcement of election manifesto promises has featured prominently in India, particularly during the 2014 general elections.

A case in point is Mithilesh Kumar Pandey vs Election Commission Of India & Ors (16 September 2014), which was public interest litigation brought by an advocate seeking, as part of relief from the court, a writ/order/direction directing the Election Commission of India "to issue directions preventing political parties from violating their manifestos when such parties enter into post-poll electoral alliances to form a government; issue directions to the competent authority to take steps to make the manifesto a legal binding document and direct the competent authority to take action against election commission for not initiating action against political parties and person for violating manifesto, and issue a direction to ban the misleading advertisement". Unfortunately, the Indian Supreme Court has rejected any attempt to use its processes to litigate unfulfilled election manifesto promises.

The issue of the breach of election promises has been a subject of debate in other jurisdictions too.

On 1 September 2016, the Thomson Reuters Legal Debates in Canary Wharf centred around the question of whether the judiciary, not just Parliament, must address breached election promises.

A vote took place, and the results on the judicial intervention motion (with 46 votes for and 48 votes against) confirmed that political accountability through Parliament and elections were preferable to accountability through the courts. This was an exciting turn of events because the pre-debate vote results stood at 64% favouring judicial intervention to address breached election promises, 11% not favouring it and 26% undecided.

I do not want to sound unreasonably pessimistic about the forthcoming local elections but experience has taught me otherwise. For communities like Letsopa, promises of a better life will be made; water will start to run through the taps as we are approaching the election date and suddenly run dry immediately after the elections.

With the prospects of broken promises, I am cleaning my vinyl player to dance to the Brenda Fassie song Promises, sadly. In this masterpiece, Fassie's lyrical message, which is appropriate to remind political parties of the empty promises they make, reads as follows:

Standing back, I can't believe how you've led me on

And judging by the things you say

There's gotta be something wrong

What you telling me that for you don't mean it

What you telling me that for I don't believe it

Your promises have never been anything you made them seem

So what you gonna promise me this time

You're telling lies so plain to see, you're trying to make a fool of me

So what you gonna promise me this time

I wanna know

Seems that I've been playing your game

And how you think you've won

But when you count up what you've gained you're the lonely one

- Omphemetse Sibanda is the Dean of Law at the University of Limpopo.

To receive Opinions Weekly, sign up for the newsletter here. Now available to all News24 readers.

*Want to respond to the columnist? Send your letter or article to opinions@news24.com with your name, profile picture, contact details and location. We encourage a diversity of voices and views in our readers' submissions and reserve the right not to publish any and all submissions received.

Disclaimer: News24 encourages freedom of speech and the expression of diverse views. The views of columnists published on News24 are therefore their own and do not necessarily represent the views of News24.