The Company, a sinister, all-controlling organization in Aliens, seemed to have intergalactic reach. It is hard now to watch the early boardroom scene in that movie and not think about Amazon, Google and Microsoft, today's planet-encircling public clouds, and where they go when Earth has been conquered. On one of Elon Musk's rocket ships to Mars, perhaps?

Authorities are nervous. Writing about "dominant platforms in the cloud market" in its October antitrust investigation, the US House of Representatives warned of "vendor lock-in" and the near-insurmountable barriers to entry. Customers attempting to move clouds typically face "high switching costs" and "technical design challenges," authors wrote. Snap, the developer of the Snapchat messaging service, said moving from Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Google Cloud to another platform would "cause us to incur significant time and expense."

Against this backdrop, Dish Network has just decided to plonk its whole telecom network into AWS. Not a chunk of its IT systems, or some of the core network functions for one market segment, but the full works. Just about the only things not disappearing into an AWS data center are the antennas and cables that software cannot eat. If Dish could find a way, those would probably vanish, too. "It is the most complete use of public cloud for a telco to date," says James Crawshaw, a principal analyst with Omdia.

Henceforth, AWS and Dish will stand in relation to each other like a feudal lord and his vassal. AWS provides territory in exchange for protection and payment. Dish works on the estate, collects money from its own customers and transfers a share to AWS. The system fell apart in 15th-century Europe, but it is making a comeback in the cloud.

Taking vows

Nobody is very worried today because hardly any telco has dropped as much as an IT server into the public cloud. Unlike Dish, most operators are not building their networks from scratch and already have lots of "stranded assets," says Crawshaw. "They aren't going to dump all that and put everything on AWS."

But some big names are pledging fealty to big tech. AT&T has said it will move all business and operational support systems (BSS and OSS) to the public cloud. With similar plans in Germany, Deutsche Telekom has already struck its own arrangement with Microsoft Azure. Some operators are experimenting with the public cloud for private networks, says Crawshaw.

The big attraction is efficiency. Becoming a tenant of AWS, with its global economies of scale, is probably much cheaper than buying servers and hosting them onsite or in a private cloud. How much cheaper? "It is way too complicated. No one knows," says Crawshaw. "But Dish is starting afresh and will have played AWS, Azure and Google Cloud against each other to get a nice price."

Resisting fealty could be dangerous, especially if rivals have no hesitation. "This news is the breaking of the dam of the old-school thought pattern," said Danielle Royston, a consultant with Telco DR and outspoken public cloud evangelist, in emailed comments about the Dish announcement. "It's not just the BSS, it's the entire network: RAN and core. If you're still deploying on-premises, your five-year capex decision is doomed to be a write-off the day you make it."

Yet if all operators were to follow that advice, three US companies would eventually host nearly all telecom systems in the Western world. Snap's experience suggests that reversing course or changing provider would be nigh-on impossible. Operators are now resisting this sort of extreme dependence in the radio access network, where Ericsson, Huawei and Nokia are still the dominant providers. But they risk stumbling into a public cloud lock-in that could be much worse.

That is because the ambitions of Amazon, Google and Microsoft go far beyond simply managing servers in giant data centers. For a start, all three are extending their cloud service offerings to the "edge," indistinct territory that lies closer to the actual user of an application. Telcos that once hoped to be the important players at the edge of the network are now ceding ground through partnerships with the public clouds. Wavelength, an edge technology developed by AWS, counts Verizon and Vodafone as two of its most prominent customers.

Captive stacks

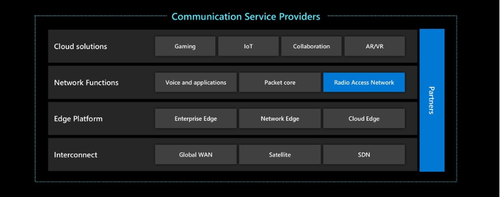

The public clouds are intruding into other technology areas, too. Last year, Microsoft bought Affirmed Networks and Metaswitch, small companies that design core network software. A marketing graphic identifies the RAN as the only gap in Microsoft's portfolio of products for communications service providers (see below).

No doubt, Microsoft is not about to start building antennas. But the Dish deal with AWS proves that even RAN functions can be hosted in the public cloud. If Microsoft saw fit to buy Affirmed, why not add a RAN software company like Mavenir or Parallel Wireless to round out the catalog?

Steve Papa, the CEO of Parallel Wireless, envisages two possible scenarios. "Either each cloud has its own captive stack or there will be a cloud with a captive stack and others with a more open stack," he told Light Reading during a conversation last year. Captive stack? That hardly sounds compatible with the philosophy behind open RAN, the concept championed by Dish. With that, operators would supposedly have the freedom to use any RAN software they like.

AWS has not bought or formed exclusive alliances with any open RAN firms, but its deal with Dish has potential implications for other vendors on the project. Mavenir, one of Dish's main suppliers of RAN software, has built its product on Intel's x86-based FlexRAN platform. Yet Dish has flagged plans to run some baseband functions on Amazon's custom-designed Graviton2 processors. What does that mean for Mavenir? The company said it could not comment.

The use of AWS processor technology implies a smaller role for Intel, too, than if Dish had decided to remain outside the public cloud. Dish is evidently taken with Graviton2, saying it provides "up to 40% better price-performance over comparable current-generation x86-based instances." Intel did not respond to a Light Reading email asking for a comment on the move.

Then there is VMware. In July 2020, Dish said the Dell-owned business would look after its multi-cloud needs, allowing it to shift workloads between public and private clouds.

Is VMware still needed after the AWS deal? "Putting an abstraction layer in place increases portability and allows Dish to go multi-cloud later, but we're not confident that the overhead is necessary," said Roy Chua of market-research firm AvidThink in a column published on Fierce Wireless.

Telcos have been experiencing an identity crisis for several years, unsure if they should be dumb pipes, technology players or something else entirely. In one possible future, they are the component parts of continent-wide communications clouds – locked in, asset-light and nearly indistinguishable from one another. It became a bit likelier this week.

Related posts:

- Dish's 5G network architect explains the new Amazon deal

- Say hello to the open RAN 'ecosystem,' or vendor lock-in 2.0

- Is open RAN a protectionist scam?

- 5G operators turn to cloud giants to get to the edge

- One consultant's plan to fill Ericsson's stand and save MWC21

— Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading