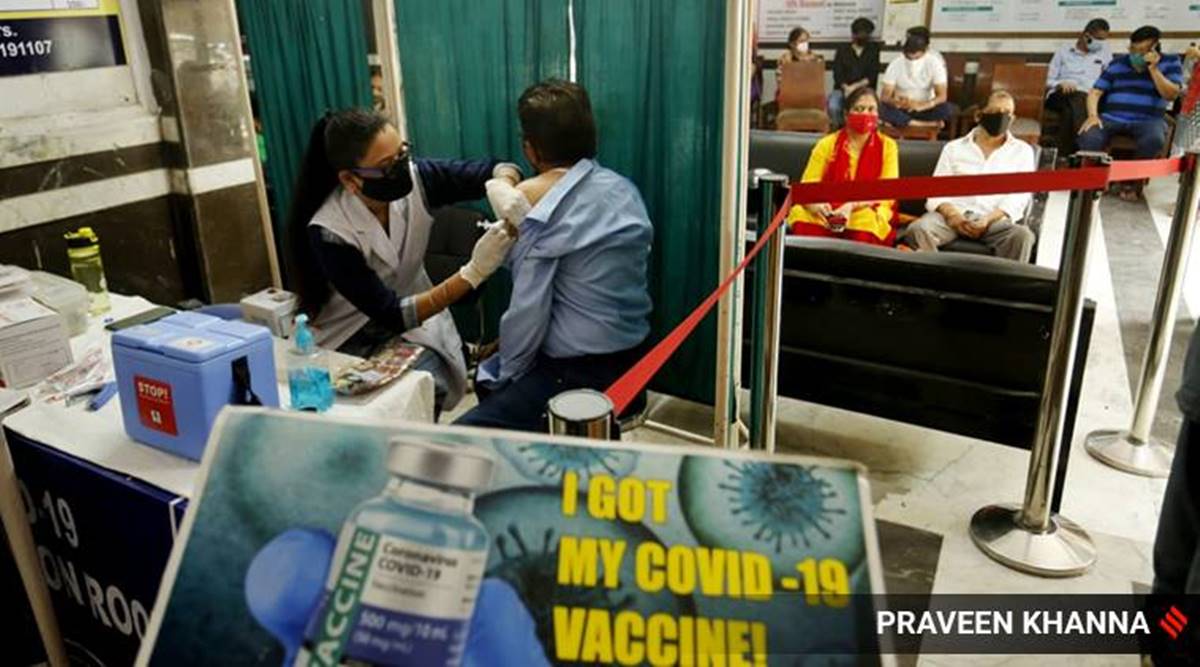

People get the Covid-19 vaccine at a hospital in New Delhi. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

People get the Covid-19 vaccine at a hospital in New Delhi. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna) In early March, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s smiling portrait appeared in the unlikeliest of places — on billboards in Toronto, Canada. A Canadian-Indian group aligned with India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was thanking Modi “for providing [the] COVID vaccine to Canada”. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared, “If the world managed to conquer COVID-19, it would be [because of] Prime Minister Modi’s leadership in sharing [India’s manufacturing] capacity with the world.”

Trudeau was right — India is playing and will continue to play a major role in supplying vaccines to the world. He was alluding to India’s massive privately-run vaccine manufacturing facility in Pune — the Serum Institute of India. Serum Institute made an early move to secure the license to produce the Oxford University-AstraZeneca vaccine, but it came with strings attached. Serum was to supply $3 vaccine shots to the world’s poorest countries through the Covax programme, a global effort to equitably distribute vaccines.

Only a small portion of all vaccines being exported by India have been donations to friendly nations. The large majority of exports are under commercial agreements Serum has made. But the government has been portraying each shipment out of the country as India’s gift to the world. Exporting more vaccines than administering to its own citizens has appeared to be a clever strategy that bolstered India’s and Modi’s image worldwide. By March 24, India had exported more vaccines than it had administered to its own citizens — 60 million doses had been dispatched to 76 countries, while 52 million doses had been administered to Indians.

Meanwhile, the Prime Minister was leading the charge for his party, holding massive election rallies with several hundred thousand mask-less supporters in attendance. The slow domestic vaccine roll out, a jubilant focus on vaccine exports and the complete abandonment of COVID protocols gave people the message that India’s pandemic was on its way out. Perhaps, Modi believed that as well — despite lessons from around the world to expect otherwise.

India’s second COVID-19 wave struck with a vengeance. India’s daily case count shot up exponentially from 12,000 on March 1 to more than 100,000 in the first week of April. More than 500 people have been dying of COVID each day in April. Caught napping at the wheel, the Modi government halted its victory lap and stopped all vaccine exports indefinitely. Under pressure from the worst-affected Indian states like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Delhi that have run out of vaccines, a senior federal health official said earlier this week, “The aim is to administer the vaccine not to those who want it, but to those who need it.”

In his address to India’s chief ministers last week, Modi announced a “tika utsav” or “vaccine festival” from April 11 to 14. But with widespread reports of shortages across the country, the last ditch attempt to save face has no takers. India has indicated it may resume vaccine exports by June in the hope that India’s latest COVID wave ebbs. But, until then, millions of people around the world who were promised Indian vaccines will be disappointed.

Poor judgment on India’s domestic requirement and the failure to back up vaccine diplomacy ambitions with adequate manufacturing capacity has meant that both domestic and international vaccination efforts have been bungled. India had three objectives through its vaccination plan — a robust domestic rollout, supply to Covax countries and vaccine diplomacy. All three could have been achieved with some foresight.

On November 28, Modi visited Serum Institute for a photo-op. He was aware of Serum’s commercial agreements. He should have seized that moment to invest in expanding capacity, but instead, his government began regulating their exports. After the recent export moratorium, Serum asked the Modi government for a cash infusion of $400 million to ramp up its capacity. The government should have done this last year when it became clear that vaccinating entire countries was the only way to protect citizens and safeguard the economy from lockdown shocks.

At the current rate, India is expected to complete vaccination of the entire population only by the end of 2023. The timelines for many developing countries across the world that were relying on Indian vaccines has also been pushed behind by several months, if not years. The world’s largest manufacturer of vaccines might end up being the last to vaccinate its people, even as Canada, which showered praise on Modi, aims to vaccinate all of its citizens by September, 2021.

Marathe is studying public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and is a former spokesperson of the Aam Aadmi Party.

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.