Whether you're a brand-new manager or have been managing people for decades, you've likely experienced the past 12 months as no picnic, as challenge after challenge pummeled workplaces around the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic, economic uncertainty, business closures, massive layoffs, widespread civil unrest, unprecedented political upheaval—these developments hit fast and furiously, and managers were the ones who had to navigate the workplace fallout. This article is the second in a series that explores those challenges, how new and longtime managers tackled them, and what they learned along the way.

Early in 2020, a new and unknown virus caught the world—and the workplace—off guard.

It was sudden. Unexpected. Universal. And many people managers weren't prepared for it.

During the past 12 months, managers across the nation used their imaginations, their budgets and their street smarts to help employees through a frightening and unpredictable year as COVID-19 cases spiked, workers fell ill and some died. They navigated the fallout as the virus shuttered businesses, cost millions of jobs, shook the economy, and left workers rattled and rudderless.

And along the way, some managers learned a few things about themselves: their biases, leadership styles, adaptability and the nature of their relationships with their workers.

Jim Christy was vacationing with his wife in Hawaii in early March 2020 when his business partner phoned to tell him that their chief of staff had sent all their employees home to work.

"Before COVID, we had fairly strict rules around limiting remote work," explained Christy, CEO of Columbus, Ohio-based Postali, a marketing agency for attorneys. "We would allow periodic remote work, but we really were an office team. It was very new … and it worried me because I like day-to-day interactions with my team. I was terrified about it."

Undoubtedly, Christy was not alone. March 11, 2020, marked the day COVID-19 was declared a pandemic and the first large-scale stay-at-home orders were issued. Many businesses told their employees to work from home. Schools sent students home and day care centers closed down, meaning working parents had to manage their kids' schoolwork and find ways to care for and entertain them after hours.

Not only was this work-from-home arrangement entirely new to some managers, but some, like Christy, also weren't sure they trusted it.

Remote Work and Distrust

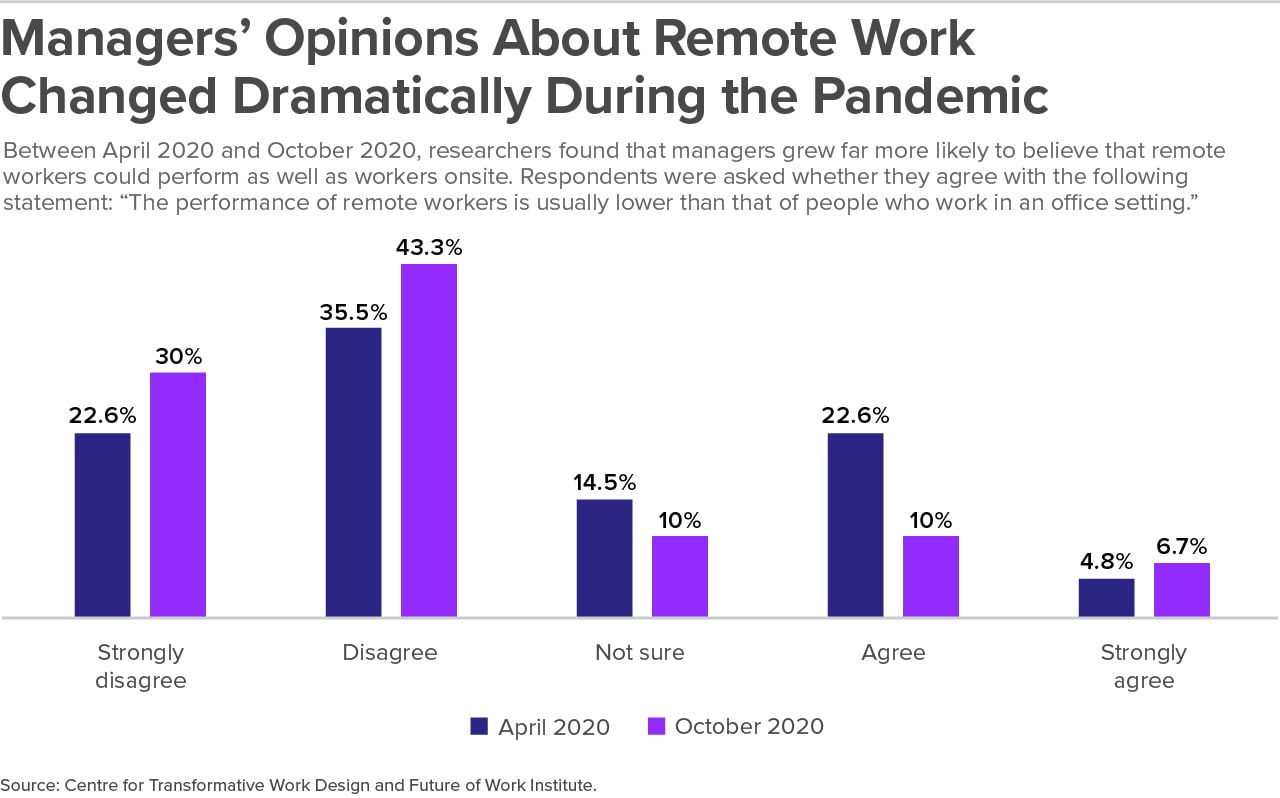

In April 2020—shortly after many employees were sent home to work because of COVID—researchers at the Centre for Transformative Work Design and Future of Work Institute found that more than 1 in 4 managers (27 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that remote workers usually perform worse than those who remain at the worksite.

When the same researchers took the pulse of managers six months later, they found a significant shift in thinking: This time, they discovered, only about 17 percent of managers agreed or strongly agreed that remote workers usually perform worse than those who remain at the worksite.

Melodie Bond-Hillman, Ph.D., is director of HR and administration with XYPRO Technology Corp., a cybersecurity and data encryption company based in Simi Valley, Calif. Before the pandemic hit, she idealized what it was like to work from home, having not done it much herself.

"You have this idea of what remote work would be like, and it's very different from what you dream of when you're sitting" at your worksite, said Bond-Hillman, who manages two workers. "Within five days, I had such new respect for our remote employees. It became crystal clear to me what their challenges are and what it's like for them not having all of us with them in the office.

"Now I understand they will have distractions. Doorbells will ring. Kids are going to need something. Someone may be mowing their lawn next door, and pets may be barking while they're on a Zoom call. If you have meetings back to back, you feel like you can't even go to the bathroom. I'm at home and 8 feet from the kitchen, and I need a break to just be able to eat.

"I tried to offer [workers] the most flexibility possible to get their jobs done and manage through this pandemic, knowing that how we treat employees during this time will not be forgotten."

|

Melodie Bond-Hillman, Ph.D., was accustomed to managing her workers in the office—in person, where she could see them daily and talk with them face-to-face when delivering instructions and feedback. Until COVID-19 hit.

“One of my biggest fears during this pandemic has been if we force everybody to work from home—and in California we’ve had to since March [2020]—employees might not participate and we’d lose touch, that we wouldn’t have the same connection,” admitted Bond-Hillman, director of HR and administration with XYPRO Technology Corp., a cybersecurity and data encryption company based in Simi Valley, Calif. So she got creative. A popular bagel shop in the Bronx was a big part of that. “I had an employee talk about how much he missed New York and felt isolated during our stay-at-home order,” Bond-Hillman said. She ordered bagels from the store and had them overnighted to her worker. When the same worker had a particularly rough week—his power went out thanks to California windstorms—she ordered more bagels. “During our company virtual coffee chats, happy hours and meetings, I try to listen to what employees are going through, and if I can help in some small way, I do,” she said. “I assume my employees are productive in a pandemic setting at home, but I also understand that they’ll have distractions and need time to adjust to a remote work setting. Flexibility and empathy while still holding employees accountable are the keys that have helped me during this pandemic as a manager.” Bond-Hillman started having daily virtual one-on-one meetings with her workers so she could better connect with them. Those daily meetings, she said, might be five minutes or half an hour. “Sometimes we go through key projects for the day and priorities. Sometimes it’s just letting the employee vent.” She and other managers arranged virtual coffee chats three times a week and virtual happy hours each Thursday afternoon for the entire company of 97 workers. Because several workers were accustomed to the company’s onsite yoga classes, managers arranged virtual yoga sessions two mornings a week. Managers brainstormed about creating new Slack channels. One is for parents to discuss the challenges of having kids doing schoolwork from home. Another is for workers to discuss outdoor activities, such as hiking. “We also encourage people to get out and be active,” Bond-Hillman said. “It’s easy to stay at your desk. So, on our calls, we encourage people to get out, get fresh air, clear your head.” Finally, managers offered employees unlimited sick time in 2020. “Our employee safety and well-being will always come first,” Bond-Hillman explained, “and that helps to create a work environment and culture that is empathetic, productive, safe and professional.” |

New Standards for a New Normal

Like Bond-Hillman, other managers had to adjust their expectations while supervising workers remotely.

Greg Besner discovered that meeting with employees via Zoom or other Web-based conferencing platforms offered a glimpse into his workers' lives that helped him see them more fully.

"People aren't necessarily showing up in their best outfit [on a Zoom call], but instead they're sitting in their home office and sometimes there's a child or pet prancing by," said Besner, a New York City-based workplace culture consultant, founder of CultureIQ and author of

The Culture Quotient: Ten Dimensions of a High-Performance Culture (IdeaPress, 2020). "Although it seems counterintuitive … being on your best behavior for 30 minutes [during an in-person meeting] is probably less insightful for a manager than having someone take a call from home and seeing the background in their home office.

"And the manager is often in the same circumstances in the home office. Before this, I was in a high-rise, and now I have a shared office with my wife. Today, my wife is sitting behind me at her desk. I think that's happening all over the world."

While talking with one's employees through a computer screen may not seem natural, it nonetheless has introduced a familiarity that managers may have come to appreciate, said Jeaneen Andrews-Feldman, chief marketing and experience officer at the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM).

"Webinars are a great example," she noted. "You might have 200 people [on a webinar] … people you don't normally speak to or see, then use breakout sessions for people to collaborate and get to know each other in a fast round of networking."

|

For a manager, there may be nothing more wrenching than having to tell a worker that he or she is being fired. During the past year, that scenario played out over and over at companies across the nation as COVID-19-related crises hammered businesses—whether they were white-collar companies losing clients who couldn’t pay, or service providers that lost customers and revenue and had to resort to pay cuts, furloughs or firings. “We were hearing horror stories about businesses chopping off entire sections of a team on short notice,” said Jim Christy, CEO of Columbus, Ohio-based Postali, a marketing agency for attorneys. Christy’s company was not immune. “Managing concerns about layoffs was a big challenge,” Christy said. “Our business serves lawyers, and many states closed courts or pushed cases far out into the future. We didn’t have any understanding of what our clients’ financial future would look like. It was possible people just wouldn’t be able to pay. This created considerable stress for everyone.” Christy and other managers decided to be candid with employees and let them know that the company’s plans could include furloughs, pay reductions and even layoffs. “We thought it was best to be direct [with employees] rather than have them dwell on the possibilities,” he said. “We spent the better part of a month in April having individual conversations with each team member about our plans and what they needed to prepare for. No one is productive when they're worried about whether they'll have a job in a month or two, but we still had paying clients that needed work done. The conversations I had with my direct reports—and they had with their direct reports—went a long way toward galvanizing the team morale and setting the tone for how we were going to lean into the challenges ahead.” Eventually, Christy’s company settled on limited furloughs. And it turned to the federal Paycheck Protection Program, which was created by the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act to help businesses, self-employed workers, sole proprietors, certain nonprofit organizations and tribal businesses continue paying their workers. Other companies weren’t as fortunate as Christy’s. The Walt Disney Co. furloughed workers and reported huge revenue losses. Yelp fired 1,000 workers, furloughed more than 1,100 and announced a 20 percent to 30 percent cut in executive pay. General Motors slashed 69,000 workers’ salaries by 20 percent before repaying the money with interest in March 2021. Kevin Miller launched a new business—with his life savings—at about the time the coronavirus hit. On the day that

SHRM Online interviewed him for this series, he had to fire someone. He’d already had to let go of another worker. The problem? Miller, a relatively young and new manager, discovered that remote work wasn’t ideal for some of his employees. There were missed deadlines and productivity lapses. “It’s hard to find the right employee who can work remotely and be productive,” said Miller, who founded The Word Counter, a Los Angeles-based online tool for writers. “I learned I had to change my management style to have daily meetings in the morning to say, ‘OK, this is what I’m working on. What are you working on?’ In the process, I discovered that when hiring, it was best to hire people based on how well they fit with the new company’s mission, not necessarily on what skills they brought from previous jobs.” Greg Besner, founder of CultureIQ and author of

The Culture Quotient: Ten Dimensions of a High-Performance Culture (IdeaPress, 2020), discovered the same thing. “In these times of remote interviewing and onboarding, it’s more important than ever to assess if a candidate is aligned with the company’s mission and values, because then it doesn’t matter where they work or when they work,” he said. “If they’re on board with the mission and values, they’re going to contribute.” |

Collateral Damage

Managing workers during the mandated closures brought about by the ongoing pandemic wasn't just about navigating remote work; it was about counseling

employees who feared getting sick or coming to work and those who resisted returning when their employers demanded it.

It was about helping workers navigate the

burnout, isolation, boredom, low morale,

mental health problems and

substance abuse that saw a significant rise in 2020.

It was about resolving disputes among workers who felt their colleagues weren't taking precautions—perhaps by not wearing masks properly or maintaining adequate social distances.

And it was about

helping workers who were dealing with a very different type of grief when loved ones died of COVID-19.

Finally, the challenges of managing workers during the past 12 months arose not only because of the global pandemic. Those challenges included helping employees with the anger, fear and distrust that erupted across the nation after the killings of unarmed Black people and during and after a presidential election that was among the most divisive and tumultuous in recent memory.

In the next article: How managers dealt with social and political unrest in the workplace.