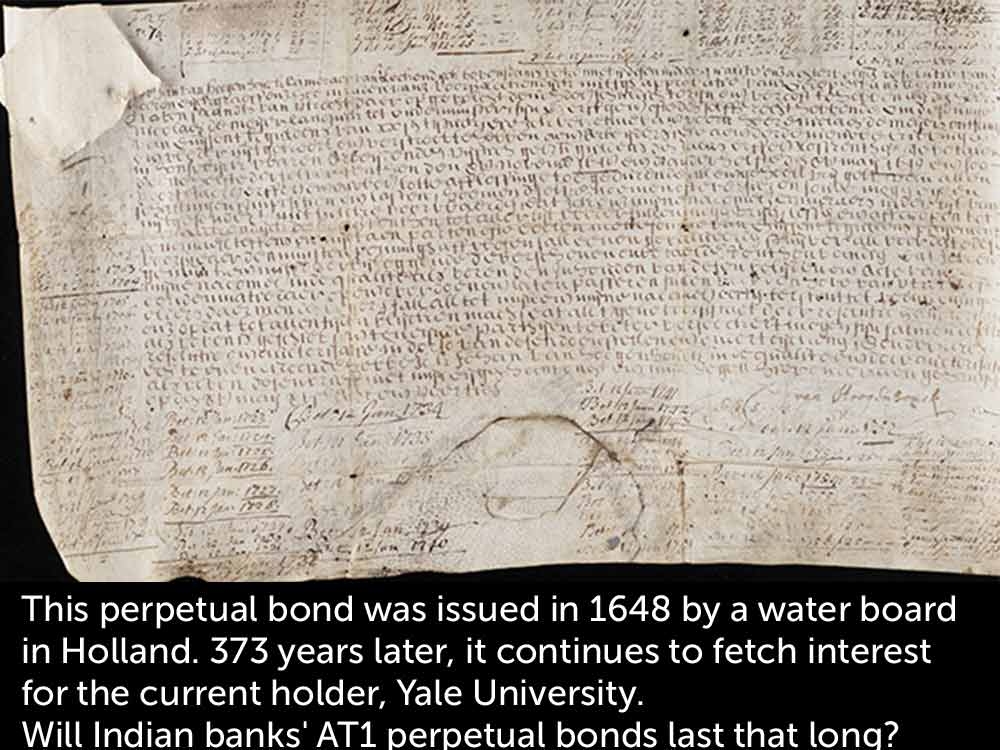

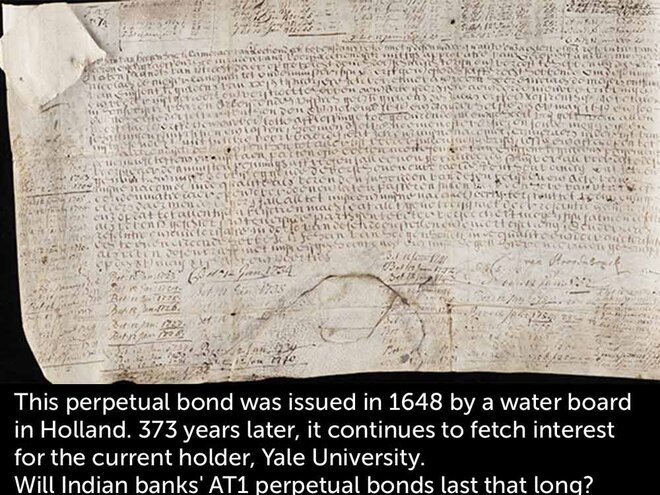

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which is part of Yale University in the United States has tens of thousands of books and documents in its collections. One of these documents is a bond issued in 1648 by an organisation named 'Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams', a water board that used to manage the irrigation and dike system in a small part of Holland during the 17th century. While the library has a lot of historical financial documents, this bond is unique because 373 years after it was issued, it's still a living contract which pays interest. The reason is that it was issued as a perpetual bond - there is no maturity.

Collecting interest is a bit troublesome because under the terms on the document, this bearer bond, which is handwritten on goat leather, has to be physically presented in the offices of the Dutch water authority, which is the successor entity to the original issuer. The last time Yale did so was in 2015, when someone travelled to Holland with the bond and collected 12 years' worth of interest, which came to 136.20 euros. The money is meaningless but the historical value of a 373-year old contract which is still honoured is far more. I think there's a reasonable chance that this may go on for another few hundred years or perhaps even a thousand years. Apparently, five copies of the bond still exist and the holders do turn up in Holland once in a while to collect their earnings.

At a time when Indian mutual funds, regulator SEBI, and the Ministry of Finance are having a degree of conflict about how to treat perpetual bonds issued by Indian banks, the story of the 373-year old bond nicely emphasises what the word 'perpetual' really implies. Would you bet on any of the perpetual bonds that have been issued by various Indian banks still being honoured in the year 2394? Obviously not. I don't know of anyone who would do so. And yet, that's what the terms and conditions of the issuance of such bonds seem to imply. To genuinely figure out the current value of a perpetual bond, one must take a view on the future, and that's the problem.

In India, perpetual bonds called 'AT1s' are issued by banks. The AT1 stands for the fact that these bonds are what is called 'Tier 1' capital of banks under the Basel III framework. You can Google and read the details but what is of relevance now is that ever since the virtual collapse of Yes Bank, AT1 holdings are considered to be potentially problematic for debt mutual funds. On March 10, in a very 'once bitten, twice shy' kind of move, SEBI put some severe limitations on the quantum and valuation of AT1 holdings by mutual funds. It said that from April 1, these bonds should be valued as if they had a 100-year maturity. Hundred years might sound like a reasonable compromise on perpetuity but the way bonds are valued, it would imply a rapid drop in value, erosion of mutual fund NAVs and most alarmingly, damage to the continued use of AT1s as a way of beefing up bank capital.

This is so important that the Ministry of Finance actually wrote to SEBI asking for a rollback of this rule. Now, after about two weeks, SEBI has modified its ruling. Over the next three years, the deemed maturity of these bonds will first be taken as 10 years, then 20 years and then finally, from 2024 onwards, 100 years.

One doesn't really know how things will actually turn out. AT1 bonds are a crucial way of funding banks as well as a good avenue for debt funds to park large amounts of assets. However, regulations or conventions that force some kind of an artificial twist in the nature of a financial instrument ought to be seen for what they are - a distortion. The reality is that perpetual bonds are perpetual - they are not 10-, 20- or 100-year bonds. In fact, the maturity period is such an integral part of a bond's character that in the normal sense of the word, they are not bonds at all. They are a unique instrument. If they are to be used widely in Indian finance, then a new set of norms is needed which recognises their true character instead of forcing them into some strange shape.