Watergate docu-maker Charles Ferguson has accused A&E Networks of attempting to delay his documentary until after the 2018 midterm elections because a History Channel executive feared it would offend the White House and Trump supporters.

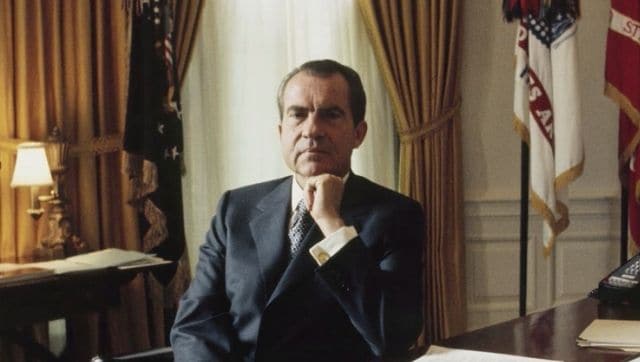

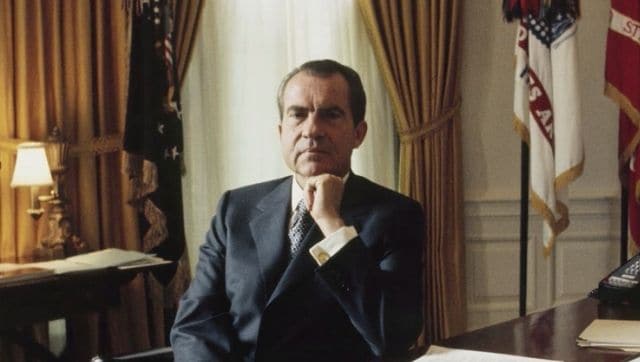

Watergate, a four-hour documentary examining the scandal that ended Richard Nixon’s presidency, had its world premiere in 2018 at the Telluride Film Festival, an event known to foretell future Oscar nominations. It went on to be shown at the New York Film Festival and several others, collecting positive reviews that highlighted allusions the series made to the Trump presidency.

It aired on the History Channel over three days in early November, just before the 2018 midterm elections. To the filmmaker’s surprise, it was never shown on US television again.

The award-winning writer and director of the documentary, Charles Ferguson, is now suing the company that owns the History Channel, A&E Networks, asserting it suppressed the dissemination of his miniseries because it was worried about potential backlash to allusions the documentary makes to the Trump White House.

In the lawsuit filed Friday in state Supreme Court in Manhattan, Ferguson accuses the company of attempting to delay the documentary until after the 2018 midterm elections because a History Channel executive feared it would offend the White House and Trump supporters.

“He was concerned about the impact of Watergate upon ratings in ‘red states,’ ” the lawsuit said of the executive, Eli Lehrer, “as well as the negative reaction it would provoke among Trump supporters and the Trump administration.”

Ferguson resisted that plan, and the miniseries ultimately aired shortly before Election Day. But the filmmaker contends the documentary was given short shrift, despite acclaim in the film industry and previous assurances that it would receive “extremely prominent treatment.”

The lawsuit describes the treatment of the documentary as part of a “pattern and practice of censorship and suppression of documentary content” at A&E Networks, and cites several others that it says were subject to attempted manipulation for political or economic reasons.

A&E called the lawsuit meritless and the assertion that the documentary was suppressed “absurd,” saying it has routinely given a platform to storytellers “to present their unvarnished vision without regard for partisan politics.”

“A&E invested millions of dollars in this project and promoted it extensively,” the company said in a statement. “Among other efforts, we hired multiple outside PR agencies, provided advance screeners to the press, and submitted it to film festivals and for awards consideration.”

Ferguson’s Watergate is a deep dive into events set off by the 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters and the cover-up by the Nixon administration. It includes interviews with people who were involved in the events — such as John Dean, President Nixon’s White House counsel — as well as reporters who covered them, including Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein and Lesley Stahl. The New York Times’ co-chief film critic, A.O. Scott, wrote that the documentary tells a story that is “part political thriller and part courtroom drama, with moments of Shakespearean grandeur and swerves into stumblebum comedy,” though other reviews panned the film’s re-creations by actors.

Ferguson, who is best known for his Oscar-winning 2010 documentary Inside Job, said that when he started pitching the project in 2015, he imagined it as a straightforward “historical detective story.” But, the suit says, a drumbeat of events involving the Trump administration made him realize the documentary’s renewed political relevance. In 2017, he watched as Trump fired his FBI director, as the Justice Department appointed a special counsel to oversee the investigation into ties between President Donald Trump’s campaign and Russian officials, and as the potential for impeachment loomed.

The series — which Ferguson said cost about $4.5 million to produce — does not mention Trump’s name, but the documentary’s subtitle, How We Learned to Stop an Out of Control President, was a nod toward his administration.

The lawsuit hinges on a conversation between Ferguson and A&E executives in June 2018, before the film was released. According to the lawsuit, Lehrer, executive vice president and head of programming at the History Channel, said at that meeting that he would seek to delay the premiere of “Watergate” and “sharply lower” its publicity profile, expressing concern about its relevance to the politics of the moment and the reaction it would provoke from the Trump administration and Trump supporters.

Ferguson has worked to collect pieces of evidence to support his contentions, among them an email he provided to The New York Times in which Lehrer acknowledged discussing the bipartisan nature of the network’s audience. In the email, Lehrer also denied the network was trying to suppress the documentary, writing that the rationale for exploring different airdates was to avoid the series getting swallowed up by heavy sports programming and election coverage.

Ferguson’s contract did not specify how many times the network would show the documentary or whether it would receive theatrical distribution, though successful ones are typically broadcast multiple times.

Nielsen ratings from the time show that Watergate earned only 529,000 viewers when it aired, including seven days of delayed viewing, compared with the History Channel’s other multi-episode documentaries like Grant which bowed in May to 4.4 million viewers, or Washington, which drew an audience of 3.3 million in February 2020.

A&E noted the documentary is available on several services, which include iTunes, Amazon Prime Video and Google Pay, including its own video-on-demand platform, History Vault.

Ferguson’s lawsuit argues that the company executives interfered with his contract, and defamed him by telling industry executives he was difficult to work with, thereby costing him work. In addition to Lehrer and Stiller, the other named defendants include Robert Sharenow, the network’s president of programming and Molly Thompson, its former head of documentary films. Thompson declined to comment. Lehrer, Stiller and Sharenow did not respond to requests for comment.

Julia Jacobs and Nicole Sperling c. 2021 The New York Times Company. Jack Begg contributed research.

Subscribe to Moneycontrol Pro at ₹499 for the first year. Use code PRO499. Limited period offer. *T&C apply